Kelly didn’t think of herself as particularly smart when a teacher told the rising sixth grader that she would be joining the Excellence Project, an after-school program at P.S. 189 in the Bronx for “gifted” students.

But she started attending the daily sessions, where Kelly got to explore topics that interest her, like her family’s roots in the Dominican Republic. The small setting was a haven from other peers who could be disruptive in the classroom during the school day.

Soon, she started thinking differently about herself.

“What changed my mind about why I didn’t think I was that special was they told us we were very talented and unique. I thought to myself that I had some talents that some other people might not be able to do,” recalled Kelly, who is only being identified by her first name for privacy reasons.

The Excellence Project was developed by the after-school provider New York Edge. With a recent $3 million federal grant, the nonprofit will soon expand into six more schools, hoping to become a model for bringing gifted programming to students who are underrepresented in the city’s own starkly segregated gifted classrooms.

“We think this can be a powerful place and space for gifted and talented education, and really, for equity,” said Rachael Gazdick, CEO of New York Edge. “If you think about the amount of time students participate in after-school programming, our ability to accelerate kids’ learning, ignite curiosity, go really deep into subject matter … there’s a lot that we can do in the after-school space.”

New York City’s gifted programs have been the subject of fierce debate. Not every school hosts one, which raises access challenges for many students. Once identified as “gifted,” students are funneled into their own classrooms or even entire schools.

While about 60% of public school students here are Black or Latino, enrollment in gifted programs is almost the inverse; most students are Asian American or white. Low-income students are also underrepresented, and there are few students who have disabilities or are learning English as a new language.

That lack of representation is often blamed on many factors. One of the biggest is how students are selected. Historically, New York City has relied on tests, though the city has recently moved to family nominations for kindergarten admissions and will use report card grades to admit third grade students starting next school year.

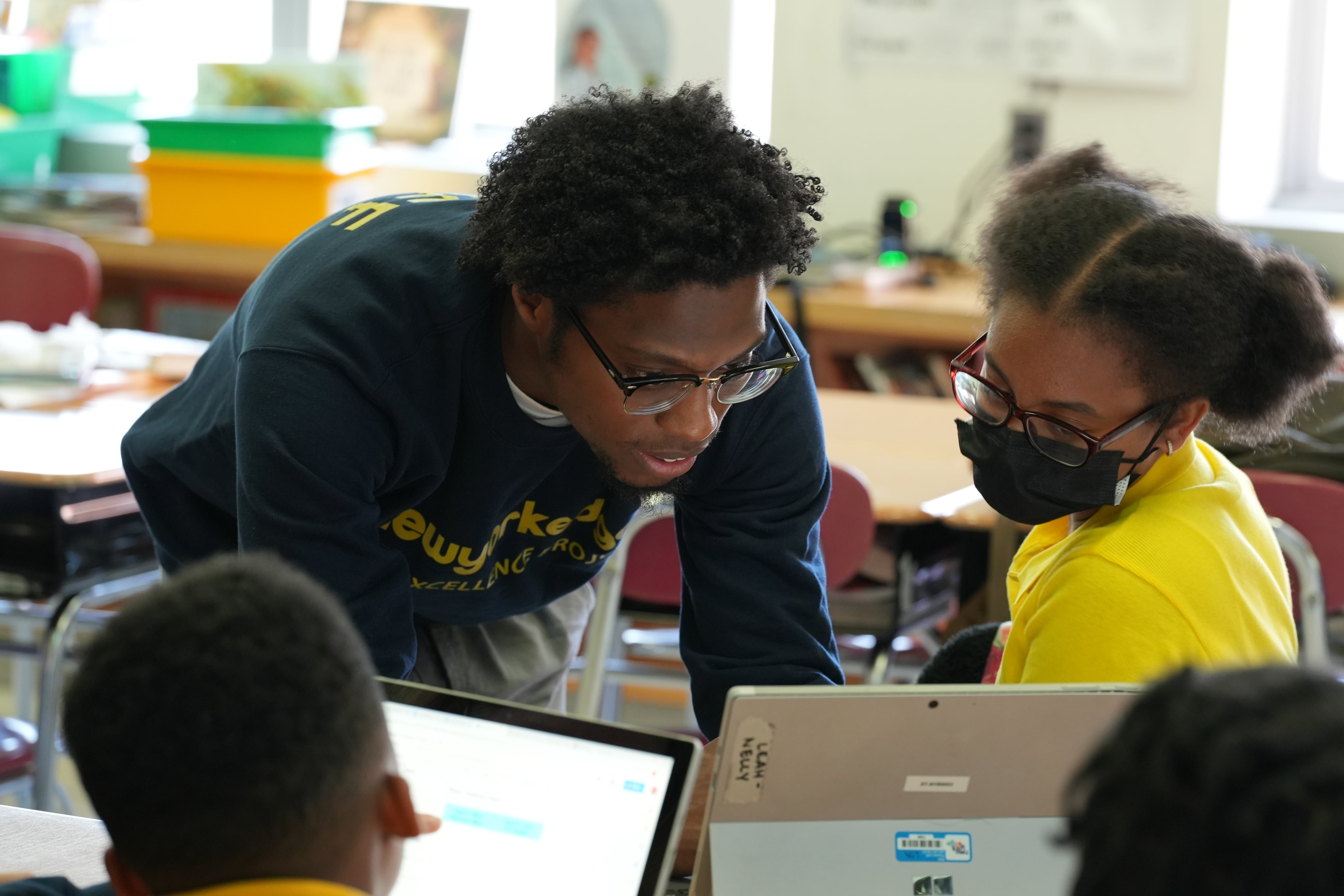

By contrast, most of the students in the Excellence Project at P.S. 189 are Black or Latino, reflecting the school population. The program opens up the admissions process even wider than the city’s approach. To participate, students can nominate themselves, or they can be nominated by a parent or teacher.

Susan Corwith, an associate director at the Center for Talent Development at Northwestern University who is not involved with the grant, said the nomination process is a good step toward more inclusive programming. But some children might still get left out if families don’t have access to information or positive experiences with their school. Teacher referrals can also be subject to biases. For those reasons, she said it’s also helpful to couple nominations with a universal approach to screening children for admission to gifted programs.

Students participating in the Excellence Project meet every school day from 3 p.m. until 6 p.m. and through the summer. The sessions are like an extension of the school day, but with more opportunities for students to lead their own projects on topics they’re curious about. Courtne Thomas, director of curriculum and instruction for the Excellence Project, said instructors incorporate student feedback from surveys into their lessons. The sessions also aim to provide enrichment through new experiences that allow students to discover and build talents.

“It’s a matter of exposure — exposure to opportunities, exposure to other cultures — through a unique model,” Thomas said. “We provide them access to thrive in what they are able to do.”

Kelly said one of her favorite projects involved meeting an illustrator and publishing a student-written book.

“I’m learning a lot of things that I’m really not taught in day school,” she said.

Marcia Gentry is the executive director of the Gifted Education Research and Resource Institute at Purdue University. She’s also an advisor to New York Edge as the organization implements the five-year grant. Gentry said she will consider the program a success if students show progress academically, but also if they are more motivated in school and have positive attitudes about their own ability to learn.

Corwith, the gifted expert from Northwestern, said the organization’s approach is similar to other programs that fall under the umbrella of “front-loading.” Those programs aim to give students access to rigorous learning experiences early in their school careers, opening up more opportunities for them later on. They hold promise and are being implemented more and more across the country, she said.

“The research indicates that this front-loading, this access to experience and enrichment does have a big impact on student achievement and performance but also on their expectation of themselves,” she said.

Christina Veiga is a reporter covering New York City with a focus on school diversity and preschool. Contact Christina at cveiga@chalkbeat.org.