Five-year-old Bradley often struggles to sit still and is prone to wandering. But on a recent Saturday morning, he was calm, sprawled on a bean bag chair in a Brooklyn classroom, the lights turned down, and his socks cast aside.

The only glow came from four illuminated vertical tubes filled with bubbles and a laptop playing soothing piano music. One therapist narrated breathing exercises while another gently squeezed his arms and legs.

Bradley, who has autism and is non-verbal, was participating in an education department program to help make up for occupational and physical therapies that were often difficult or impossible to deliver remotely. The initiative, called Sensory Exploration, Education & Discovery (SEED), serves students with disabilities who have sensory issues that are “dramatically impacting their school performance,” said Suzanne Sanchez, the education department’s senior director of therapy services who helps oversee the program.

The SEED program operates after school and on Saturdays at 10 sites across the city — two in each borough. It’s part of a broader effort backed by roughly $200 million in federal relief funding to provide students with disabilities extra services outside of the traditional school day to address pandemic disruptions, Sanchez said.

To participate, students must be nominated by therapists or psychologists from their home schools. More than half come from District 75, a specialized set of schools that serve students with the most significant disabilities.

Once selected, students are eligible to attend at least 10 weekly 45-minute sessions where they receive help from therapists one-on-one or in small groups. They work on skills such as developing strength and coordination, learning to build social bonds, or even how to react if someone bumps into you, which can trigger a more intense response among students with sensory issues.

“Children have to be regulated in order to relate and then in order to reason,” Sanchez said. “The goal is that the kids internalize the sensory strategies.”

The therapists also work directly with caregivers, who are required to stay for the sessions, giving them approaches to try out at home.

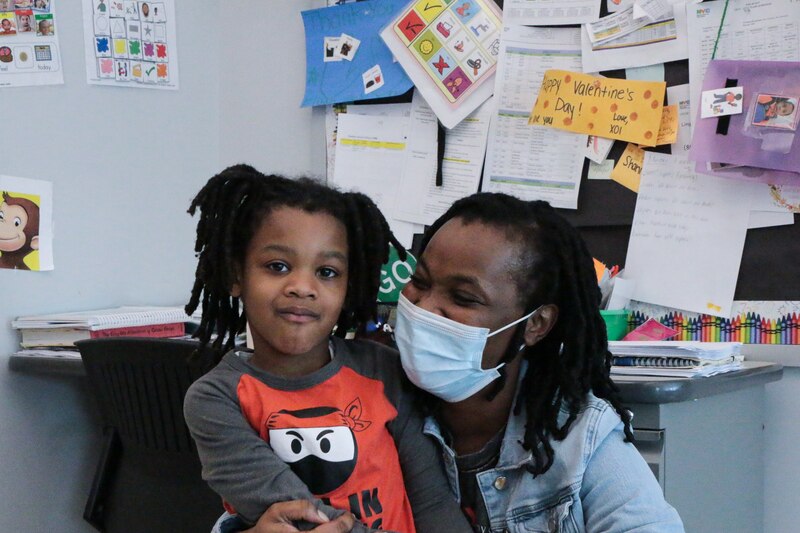

Bradley’s mother, Patricia Hector, said the therapists helped teach her to massage Bradley’s arms and legs to help soothe him. She also bought some of her own glow-in-the-dark lights after she saw how much they seemed to calm him down.

“Going to the program, he’s a lot happier — he enjoys it,” Hector said. “Anything extra to expose him — to get him more of the therapies he needs.”

But the city has struggled to attract families to recovery services for students with disabilities outside the regular school day at programs run by individual schools as well as the SEED program, which is operated centrally. To date, roughly 650 students have participated in the SEED program, short of the 3,500 children the education department projected to serve by the end of the year, officials said.

Some families may struggle with transportation to sites that may be further away from where they live. Hector, for instance, takes a 25-minute Uber from East Flatbush to the program in Cypress Hills. She gets reimbursed for her travel through a state agency.

Other students with disabilities may be exhausted and reluctant to spend even more time in school. And a surge in COVID cases when the SEED program launched in January dissuaded some families from participating, Sanchez said.

“Obviously we want to reach as many kids and their families as we can,” Sanchez said. But she noted the smaller numbers allowed the city to shrink group sizes to two or three students in many cases. “We feel like this is an opportunity to focus on quality not quantity.”

In the ‘green zone’

After Bradley’s session ended, a group of three slightly older students arrived and began gliding across the linoleum floors on small scooters. They completed a small obstacle course, jumped on a trampoline, wiggled through a tunnel, and climbed up the rock wall.

Soon after, 8-year-old Adrian Soriano took a turn tossing bean bags from a perch on the sensory swing. Each bean bag had a letter printed on it, and Soriano shouted out a corresponding word — “N is for nut!” and “D is for dog!” — before chucking them into a blue bin.

The therapists encouraged Soriano to take stock of his emotions, using a color-coded chart from red (angry) to green (happy) meant to help students communicate whether they’re feeling sad, calm, annoyed, or out of control.

“What zone are you in?” one therapist asked, after ticking off several options.

“Green zone!” Adrian replied.

At one point, another student became overwhelmed and retreated to a “sensory canoe” — a small pouch made out of mats — before rejoining the group.

Although the SEED program is housed inside different public school buildings, the centrally run program has a standardized curriculum developed by education department therapists. The rooms across the sites include the same equipment, and the walls were repainted a uniform blue and white.

Since the program is considered enrichment, Sanchez said it is not bound by individual students’ learning plans, known as IEPs, which therapists typically use as a blueprint for sessions delivered during the regular school day.

“This idea of being a little more prescriptive is I think something that’s surprising us — but for the better,” Sanchez said. “It’s this kind of nuanced dance: How do we make a therapeutic curriculum fit with an individual IEP?”

Ketsia Bosse-Colasme, an occupational therapist, said she was excited to work at the SEED program because it allowed her to use sensory techniques and equipment that most classrooms don’t have. Typically, during the school day, Bosse-Colasme focuses more heavily on handwriting skills or helping students use a planner during a 30-minute session.

The program is making a difference, she said.

“I have kids who first came here and they did not talk,” she said. “By the fifth session or the seventh session, even if it’s a simple ‘hello,’ or even saying, ‘I’m happy,’” she has seen students come out of their shells.

Planting SEEDs for summer

Parents cycling in and out of the gleaming Cypress Hills SEED site on a recent Saturday generally said they were pleased with the program, and the education department plans to continue it at five summer school sites where they expect it will serve about 400 students.

Still, there have been some administrative problems. The education department failed to pay many therapists on time, prompting at least one to quit the program midyear.

Education department spokesperson Suzan Sumer said addressing outstanding payment issues is a priority and that “most” have been resolved. She declined to say many therapists have left the SEED program or answer questions about its cost.

Alicia Hibbert, whose 11-year-old son attends the Cypress Hills site, said she wanted him to participate in part to help develop social skills after so much isolation. Her son, who has autism, would often ask when the pandemic would end so he could see his friends again.

Over the course of the program, she has seen growth. He is working on improving his eye contact and staying calm when he feels frustrated, which can manifest by hitting himself in the head.

“He’s getting some improvement here, which I like,” Hibbert said. “He’s improving his basic skills.”

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.