The morning after hundreds of New Yorkers asked the education department to pause its plans to reopen campuses, Mayor Bill de Blasio instead asked educators to step up and serve.

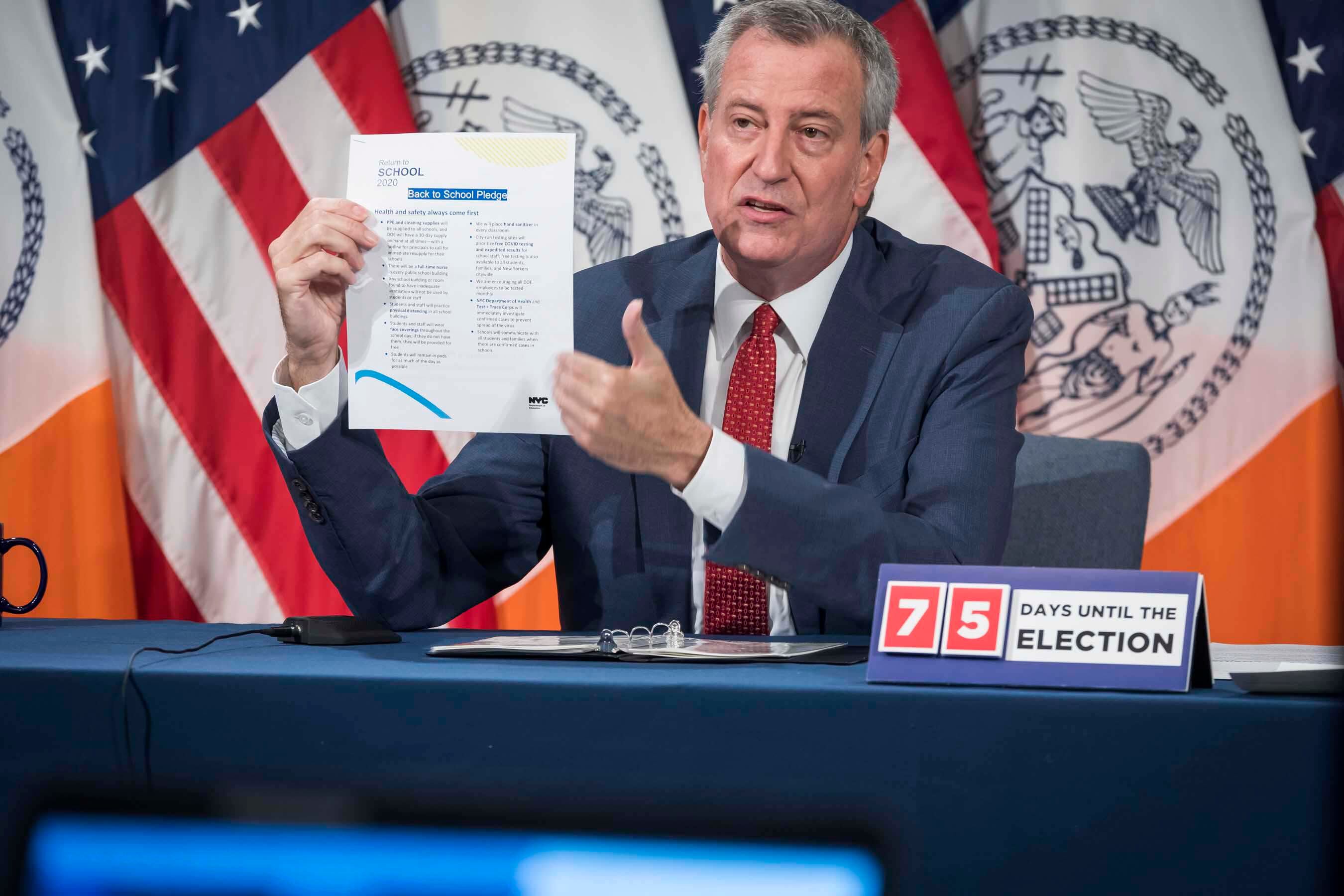

The mayor doubled down on his push to reopen schools on Sept. 10, unveiling on Thursday a back-to-school pledge, outlining the city’s health- and safety-related commitments to school communities.

“Educators chose the profession because they love kids and they care about kids, and they know kids are suffering right now,” de Blasio said. “It’s time to say, public servants rise to the occasion and answer the call. Our transit workers did, our first responders did, our health care workers did, our grocery workers did.”

But many feel that the mayor — who ultimately controls city schools — has not given them the guidance and resources to make a safe return feasible. De Blasio’s promises to provide sufficient safety masks, cleaning supplies, and full-time nurses in every school building, among other resources, is doing little to assuage the concerns of many teachers, who want more than a checklist. It also fails to answer some major curriculum and staffing challenges that principals must resolve before opening their school doors.

Moreover, the city has shifted the burden of responsibility onto parents to decide whether they will return to school buildings or go fully remote. Roughly 30% of students have so far opted into fully remote learning, but those numbers are growing by the day, principals said, making planning difficult. Meanwhile, the number of teachers the city will permit to work remotely is also unknown.

“Teachers love kids. That is true. And we love educating them,” said Deirdre Tuite, a high school teacher at Long Island City’s Academy of American Studies. “Schools can have all the PPE available, but it’s more than that.”

She and other teachers want to know, for instance, what bathroom policies will look like and how children will be escorted to the nurse’s office.

“We are teaching [students] that they need to question what is not fair,” Tuite said.“ That is our job.”

The mayor promised that classrooms or buildings without proper ventilation will not be used this year. Teachers — many of whom have worked in poorly ventilated spaces for years — remain skeptical.

The teachers union has threatened to take legal action or even strike if their demands, such as COVID-19 testing for all students and staffers entering buildings, aren’t met. MORE UFT, a social justice arm of the teachers union, ratcheted up the threat of action.

“If the UFT does not follow through on its promise to stop schools from reopening unsafely, then the rank and file will take action to protect students and their families,” according to a statement the group issued on Thursday. “It’s time to stop wasting time on a reopening plan that will fail, and instead focus energy in making remote instruction as effective and equitable as possible.”

Principals meanwhile are hearing from both teachers and families while feeling overwhelmed by the lack of guidance not only on safety issues, but also on curriculum and staffing. School leaders are still struggling with how to staff their blended classrooms of in-person and remote learning. They still don’t know whether an in-person teacher can contractually teach remotely. They say they’ve received no guidance on how to provide services to students with disabilities or those learning English as a new language.

Nearly 30 principals in Manhattan’s District 2 sent a letter to the mayor, Chancellor Richard Carranza, and Gov. Andrew Cuomo on Wednesday, asking them to delay reopening school buildings — joining the ranks of principals in Brooklyn districts 13 and 15, and Manhattan’s District 6. With class sizes of roughly 10 students, the Manhattan principals said they need double or triple the number of teachers. Despite asking on a “near-daily basis for months” how to fill those gaps, they’ve received no guidance, they said. And high staffing needs comes at a time when state budget cuts could mean 9,000 fewer teachers, Carranza warned Wednesday.

“Now, as the summer days wane and we barrel towards September, we can no longer ‘await further guidance’ on many important issues,” District 2 principals wrote. “It is untenable for us to plan — let alone open our school buildings in a matter of weeks — without critical policies and resources.”

Amid the uncertainties, schools are giving staff just two days to clean out classrooms — frozen in time since last March — and get ready for learning to teach in this new reality.

“This is very traumatic for staff coming back,” said Nancy Harris, founding principal of Spruce Street School, a K-8 school in Lower Manhattan.

While Harris said she’s up for a challenge, “the math doesn’t add up.”

“I like a good puzzle,” she said, “but this is a faulty puzzle. There are 100 pieces missing out of the jigsaw box. It doesn’t matter how hard I try.”