New York is releasing $65 million in federal money to help preschools and day care centers reopen after the coronavirus forced many to close down. But providers in New York City say the money falls woefully short of what’s needed to prop up an industry that will be essential for families getting back to work.

Making matters worse, it’s unclear whether early childhood programs that are under city orders to remain closed will be eligible for the grants, since the money requires businesses be up and running by July 29. The city has offered no projections on when it will allow the approximately 3,000 programs it oversees to reopen.

The leaders of preschools and day cares across the city will rally on Saturday to demand a bailout for their businesses. In an industry whose workforce is dominated by women of color, many feel they are a forgotten but necessary part of reopening the battered economy. While city leaders have scrambled to make outdoor dining possible for restaurants to open back up, many in the child care sector say there’s been no comparable public push to save their businesses.

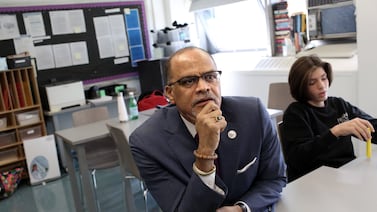

“Every day there are programs closing,” said Andre Farrell, who has lost two of his own Brooklyn child care sites since the pandemic gripped the city, and is helping organize this weekend’s demonstration. “It’s going to get even darker, I believe, because there’s nothing really being done.”

Gov. Andrew Cuomo on Tuesday announced that the state would tap money from the federal CAREs act to offer $20 million to child care centers to help pay for social distancing measures, such as partitions or cleaning supplies, or training and hiring more teachers. Another $45 million will go towards helping centers pay for operating costs, such as renting space to open more classrooms — grants that would top out at $6,000 and phase out after only three months.

“That is not going to resurrect childcare,” said Gladys Jones, who has taken care of young children for decades out of her Staten Island home on the North Shore. “In order to survive, we need money.”

Jones tried to keep her doors open through the pandemic, but enrollment evaporated. All 16 of her students have pulled out because their families can no longer afford to pay or because they’ve enrolled in the city’s own emergency centers, which are free.

If Jones is able to lure families back, social distancing requirements mean that she can only serve 10 children. Public money will be needed to fill the tuition gaps caused by operating under capacity, or else it won’t be financially viable to reopen.

“You have to make that money up,” she said. “This does not look good.”

A recent report by the Day Care Council of New York, which represents the boards of more than 200 publicly-subsidized providers in the city, suggests that centers need help paying for fixed costs such as rent while operating at just a fraction of normal capacity.

“Providers noted that taking the very measures needed to protect the health of their staff and families — for instance, reducing the number of children served — threatened their financial viability,” the report read. “As the city prepares to reopen its early education system, efforts to ensure the health and safety of families and staff must come with financial assistance.”

Home-based programs such as Jones’s are regulated by the state and have been allowed to remain open throughout the coronavirus outbreak. But some 3,000 commercial day care centers and preschools licensed by the city were ordered shut on April 6. Eager to reopen, operators have gotten no guidance for when they might be able to do so.

“We’re bleeding money,” said Fabiola Santos-Gaerlan, who runs programs in Park Slope and Kensington that have been closed for months. “This pandemic showed that we are on our own. We are caring for the babies and the workforce, and we’re on our own.”

She is scrambling to apply for summer camp licenses since the city is allowing camps to operate. With that, she’ll be able to serve 10 children for camp, along with another 10 in a home-based day care she also runs. That’s a fraction of typical enrollment of just under 100 students for her business, Honeydew Drop Family of Childcare Services.

At a press conference this week, Mayor Bill de Blasio called reopening childcare one of “the toughest pieces of the equation,” in terms of reopening and ensuring public health, saying most centers don’t have the space needed to operate safely.

“It has been really tough to figure out how we can do that in a healthy manner,” he said.

Yet the city has been operating child care centers at public schools, and contracted with more than 100 community providers to serve frontline workers, without any notable outbreaks.

“It’s definitely been proven that reopening is possible,” Farrell said. “Why are we being squeezed to a point where we can’t open and everyone else is able to?”

City council members have mounted pressure on the city to release a timeline and guidance for reopening centers, while demanding the state follow in the footsteps of dozens of others and invest its own money for the sector.

“The state and city are failing NYC parents, child care providers, and our city’s economic recovery,” council members Brad Lander and Deborah Rose said in a joint statement. “There is simply no way that our city can successfully rebuild our economy without affordable child care for working parents.”

In all, New York state got about $164 million in federal money to spend on the sector since the coronavirus pandemic took hold. In addition to the grants announced this week, another $30 million has been spent on subsidizing child care for front line workers and paying for protective gear and clearing supplies. (That leaves $69 million leftover.)

Many states are worried they won’t see additional federal support for recovery, and are trying to stretch out the dollars they’ve already been allocated, said Stephanie Schmit, a senior policy analyst on childcare and early education for the Center for Law and Social Policy, an anti-poverty advocacy group. Congress has not acted on proposed legislation that would dedicate $50 billion to the sector, and is still wrangling over the next round of federal stimulus spending. Child care in New York alone is estimated to be a $4.2 billion industry.

“The resources, while incredibly needed, are very limited,” said Schmit. “There’s not enough money to go around.”