Warning that child care businesses and private preschools might not survive the prolonged coronavirus shutdown, dozens of New York City Council members are asking the governor to extend a lifeline to the sector.

More than 20 elected officials from the city sent a letter Tuesday calling on Gov. Andrew Cuomo to direct $134 million in federal stimulus money as grants to child care providers and families.

That is remaining funding from $164 million designated for child care assistance through the CARES Act. So far, the state has used the money to subsidize care for low-income families working on the front lines, and to pay for cleaning supplies and protective gear at day cares and preschools.

“New York State cannot reopen our economy and begin to recover from the COVID crisis without access to affordable, high-quality child care for working families,” the letter stated. “Unfortunately, there is a very real possibility that many of our State’s child care providers will fail over the next few months and close their doors.”

Freeman Klopott, a spokesperson for the state budget division, said plans for how to spend the remaining stimulus money are still being crafted “in order to ensure critical access remains available statewide.”

Most child care centers are independently run and do not receive public subsidies, yet their services are essential for families who need to work. Advocates have said public money will be critical to keeping the sector alive. New York City families already pay preschool and day care tuition rates that rival college costs. As many parents have lost their jobs during the pandemic, paying for child care will be out of reach, and many in the child care sector — which employs more than 130,000 in the state — could also be jobless.

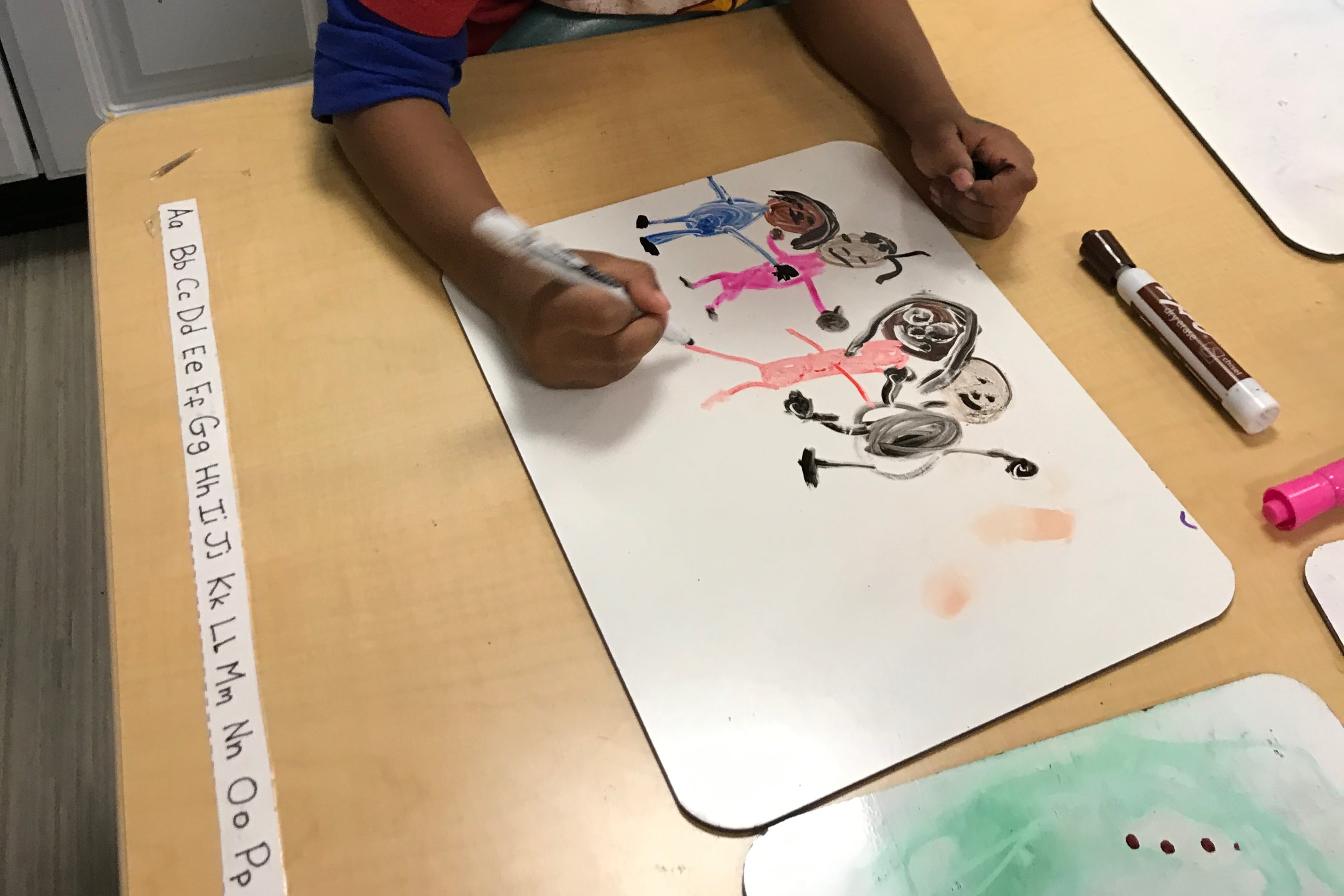

“A failure to save New York’s child care industry will impact workers in every county of New York State and reverberate throughout every sector of the economy,” according to the letter from the elected officials. “It will set back an entire generation of young minds that will be denied an early start to learning and socialization.”

The council members also want the state to focus on supporting private preschools that enroll children with disabilities, which have faced seat shortages since well before the health crisis began.

Andre Farrell, who founded a trio of preschools in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn permanently closed two of his locations in recent weeks. The third outpost of the Katmint Learning Initiative is hanging on with a skeletal staff doing virtual learning with half of its students paying a fraction of the typical tuition.

“We feel totally alone,” Farrell previously told Chalkbeat.