Nearly all of the Community Education Councils across the five boroughs are out of compliance with a state law requiring non-voting high school seniors on their boards, New York City Education Department officials confirmed.

Each of the city’s 32 local school districts has a Community Education Council, or CEC, with 10 elected voting members and two appointed by the local borough president. Since 2022, state law has required CECs to also have two non-voting high school seniors, up from 2003′s one-student requirement. There are also four citywide councils that must have one non-voting high school senior.

CECs are advisory bodies that evaluate educational materials and policies and hold public meetings alongside the district’s superintendent. Adult members also have voting power on one issue: district zoning changes. Student members have all the advisory powers of their adult counterparts, though they cannot vote on zoning changes.

Some students and youth advocates say students should have a greater role in education policy decisions, and serving on education councils is a way to do that. Yet few students even know about the CEC positions.

“A lot of the times youth are looked down upon, like we’re not capable enough to make our own decisions on what we get to learn,” said Nazrin Nahar, spokesperson for the youth-led advocacy organization Integrate NYC and a 20-year old student at Baruch College. “We want representation.”

When she went to Forest Hills High School in Queens, Nahar never heard about opportunities to serve on education councils.

“I never knew about this opportunity until now,” Nahar said. “So there definitely needs to be more transparency, and students need to be told about this possibility.”

The Education Department’s bookkeeping on the student CEC members seems to be incomplete and outdated — raising questions about how much attention city officials are paying to the matter. The department’s website states that all CECs and citywide councils have student vacancies. But in response to an inquiry about it, officials said that two CECs, District 9′s in the South Bronx and District 25′s in Flushing, Queens, have an appointed student representative.

Meanwhile, members of the CEC in District 14, representing Williamsburg, Brooklyn, as well as the Citywide Council on Special Education told Chalkbeat they also have student representatives. Education Department officials, however, said those councils do not have officially appointed student representatives, and declined to comment on the discrepancy.

After publication of this story, a student representative on Staten Island’s CEC let Chalkbeat know about her role.

The state does not collect or request information regarding vacancies on the city’s education councils, according to New York State Education Department officials.

Some councils reported vacancies dating back to July, when the new term began. Others said that their vacancies have been chronic.

“I’ve been on the council for three years, and I can say we haven’t had a student representative in my tenure,” said Anderson David, the recording secretary for the council in Brooklyn’s District 18.

Deborah Kross, the president of the citywide council on high schools, said that there has never been a student member since she joined the council in 2021.

“This is really unfortunate,” Kross said.”I hope we can fill that seat as we would welcome the opportunity to have a student on the council.”

Education Department spokesperson Chyann Tull said they encourage the councils to have student representatives. “We spread awareness of these opportunities through superintendents, central staff and council leaders.”

Eligibility barriers might shut students out

Superintendents are involved with the student selection process, Education Department officials told Chalkbeat, but information posted online states that the Division of Family and Community Empowerment, or FACE, is charged with collecting all student applications and appointing representatives.

State law sets additional requirements for students: Only high school seniors who are already part of “elected leadership” are eligible to apply.

Students must also reside in that CEC’s geographic area, which can be challenging since many high school students attend schools outside of the geographic district in which they reside, according to Education Department officials. (The CECs oversee K-8 schools, not high schools.)

Veronica Morris, a 17-year-old junior at New Explorations into Science, Technology and Math in Manhattan and a member of Integrate NYC, took issue with the eligibility requirements to be seniors and to have prior experience in student government. Also, since life outside of school is busy and complicated for many students, Morris said, many potential student leaders wouldn’t be considered.

“If you have to take care of siblings or work to raise money for your family or whatever, that’s going to stop you from joining student government in the first place or if you’re in student government, [it will stop you from being] on one of these boards,” Morris said.

Nahar said that she thinks younger students may tend to be more interested in being involved anyway, since seniors are often focused on their futures outside of school.

“A lot of seniors are already busy with their college apps, this is not their priority right now,” Nahar said.

John Liu, a state senator from Queens and the chair of the senate’s New York City Education Committee, said that the cause of the student vacancies must be “either insufficient outreach or insufficient interest,” but that he tends to believe there is plenty of student interest.

“Wherever I go it seems like students want to have more of a voice and many parents are supportive of them having a voice,” Liu said. “However, I’ve also heard some feedback from CECs as well as the DOE that they don’t have enough interest.”

Some students don’t feel welcome on parent-led boards

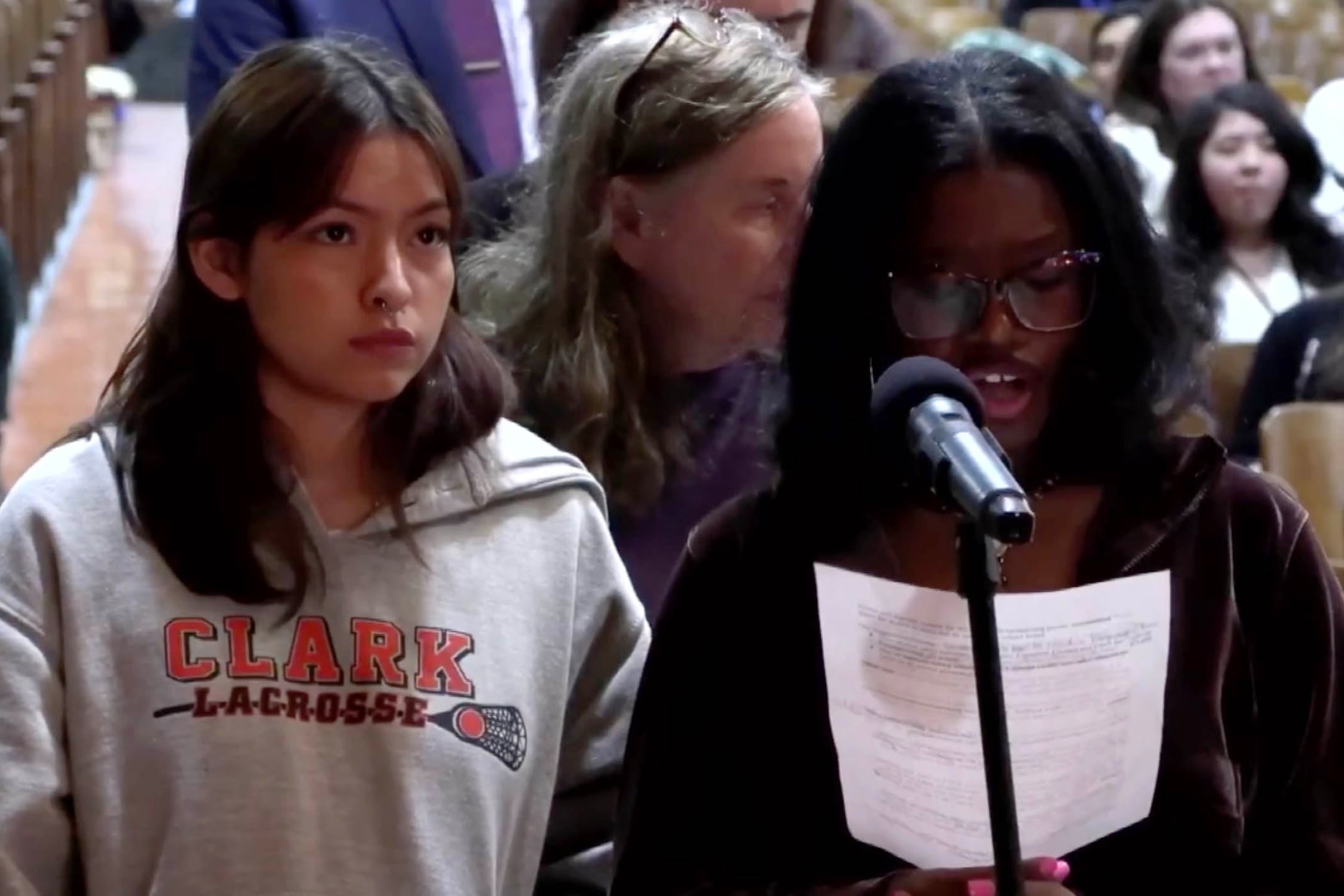

The city’s Panel for Educational Policy, which is the board that votes on major Education Department decisions, including contracts and school closures, has one student representative, and that seat is filled by Aissata Diallo, a 17-year-old senior at James Madison High School.

Being on the panel has been one of the “biggest highlights” of her high school career, she said. “Being able to sit in on these notoriously adult spaces and have a voice,” she said, is what makes it such a good experience.

But being the only student on a board full of adults can be challenging, and she wishes there were more student representatives on the panel so young people who do participate feel supported by peers.

“It gets a little lonely sometimes, being the only one there,” Diallo said.

Maggie Handelman, a 16-year-old junior at LaGuardia High School and a member of Integrate NYC, said the lack of other students on education councils makes such spaces feel inaccessible.

“Walking into an all-adult space that is not made for you and you are one of like two youth feels very intimidating and not welcoming,” Handelman said.

Additionally, Handelman said that from experience advocating in adult-dominant spaces, she thinks that young perspectives are often “tokenized.”

“They’re like, ‘We love to hear from students’ but then they don’t take you seriously,” Handelman said.”

Handleman said that student representatives on education councils should have voting power.

Tajh Sutton, the president of District 14′s council, agreed. Sutton said CEC 14 amended their bylaws to include a student advisory council, giving opportunities for representatives from middle and elementary school.

“In order to make the student seats on CECs and citywide councils worth being on, we’d first have to create the spaces within the CECs and citywide councils where children are welcome and celebrated and actually listened to and given a voice and a vote,” Sutton said.

Anyone with information that a council is not fulfilling its legal responsibilities may contact the Department’s Office of Education Management Services via email to emscmgts@nysed.gov or by phone at 518-474-6541, state officials said.

Julian Roberts-Grmela is a journalist based in New York City.