It was in the days and weeks after 9/11 that Elana Rabinowitz, then working in advertising, decided to become a teacher. “When the towers collapsed and the tone of the city changed, I did, too,” she said. “I wanted to help people, desperately.”

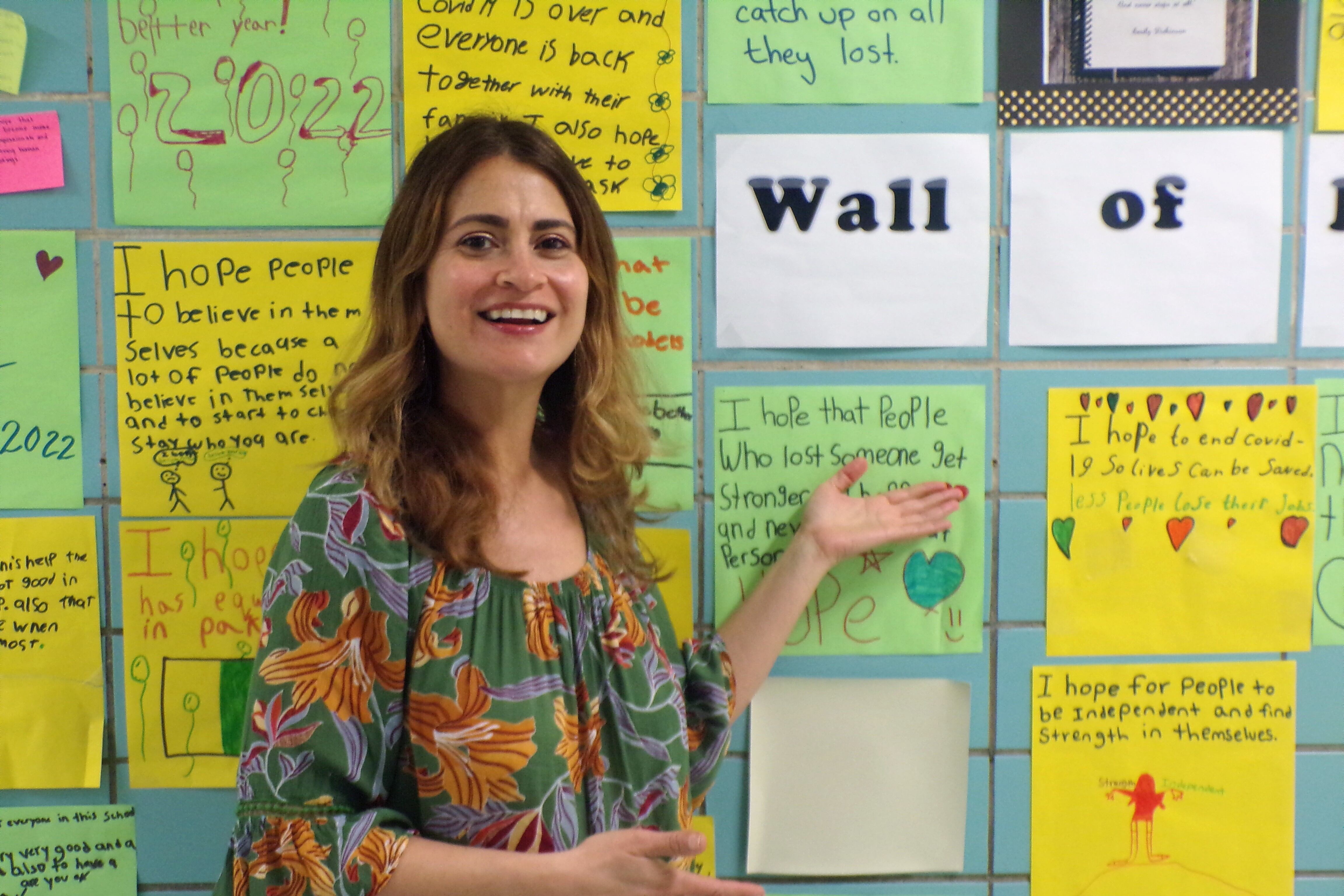

Rabinowitz had worked abroad and already had a certificate in teaching English to speakers of other languages, so she put her skills to work in the classroom. More than two decades on, she is an ESL teacher and coordinator at Middle School 113 The Ronald Edmonds Learning Center in Brooklyn.

In recent years, many of her students have been recent arrivals to the United States — children from asylum-seeking families who fled violence and economic hardship. Some of them had been out of school for months or years as they made their way to the U.S.

Rabinowitz wants them to feel comfortable sharing their stories and identities. As soon as a new student is placed in her class, Rabinowitz buys a flag from their country of origin. But she wants them to feel at home in New York City, too, so she decorates her classroom with cozy secondhand furniture she finds at stoop sales.

When New York City Public Schools started earlier this month, an estimated 21,000 new migrant children had enrolled. As a longtime teacher of new arrivals, Rabinowitz spoke to Chalkbeat New York about how educators and families can help support English learners in their school communities.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

What drew you to teaching English learners?

I was already on an international path. I had been in the Peace Corps in Sri Lanka. I had run a language school in Ecuador. I had become proficient in both Sinhala and Spanish. I knew that learning the local language was the key to connecting with people. I wanted to do that for someone else.

What’s your favorite lesson to teach and why?

Anything that involves writing, even if it is just a picture and a word. I love when the students at every level can express themselves in prose. I find that poetry is often the universal form of communication, and anything from an acrostic poem about their ancestors to a sensory poem about their homeland always gives me the chills. It is giving students a voice who may not feel that they have one in another class, and their work is often spectacular.

Back in 2019, a student of ours was one of only 33 Latino students accepted to Stuyvesant that year, amid the controversy around specialized high school testing. I immediately wanted to know how he felt about it and was able to work with him to get his first op-ed published. He even got paid! Now that was a great day.

What’s something happening in the community that affects what goes on inside your classroom?

The recent arrival of asylum seekers. The most recent arrivals have banded together to become fast friends. It’s funny how many teachers and staff suddenly know Spanish now and use it to make our students feel comfortable. When new arrivals are placed in my classroom, I immediately order flags from their countries.

Last year, two of the girls grabbed their flags and started singing Ecuadorian and Venezuelan pledges of allegiance in Spanish. It was beautiful. I try to incorporate aspects of their cultures in my classroom whenever possible. Many of my students are fantastic artists, so they paint scenery from their countries, and we display it in my room to remind them of their homes. I also add pictures of activities we do together to let them know that this is their home, too.

What new issues arose at your school or classroom last school year, and how did you address them?

Having such a large group of newcomers arriving at once. We now had students who spoke little to no English sitting in classes. Many had missed months, if not years, of school and came with so many needs. A group of us banded together to make sure they had appropriate clothing, school supplies, and emotional support. It was the heart of winter, and kids were coming to school without socks or jackets!

This support is ongoing. Once funding was established, we were able to create morning, after-school, and Saturday academies specifically to assist our newcomers in their transition. The students would learn English by doing — making waffles, playing soccer and basketball, painting pictures, and doing neighborhood walks, which ended in ordering pizza from a local pizzeria. They particularly liked learning how to order pizza!

How do you think schools and educators can better meet the needs of immigrant and refugee students?

First off, stop with the ridiculous Spanish LAB, which is used to measure English-language proficiency. The test they have me administering is from 1982, the same year Michael Jackson sang “Thriller.” We need updated assessments in their native languages that can be scored before a child enters a school.

Also, newcomers need more English than the 360 minutes a week. At minimum, their first six months should be spent with intensive English courses. They can attend gym, math, lunch, and one other elective with their English-speaking peers, but the idea of having a child with no English sit in an ELA class is preposterous. Many teachers just put them on a computer all day or hand them translated text with no instruction. It is demeaning and staggers learning. These students have already been through enough to get here; we should be making them feel more comfortable — not lost or different.

What can families do to support migrant families in their school community?

Families and the local community can help by assisting with translating, donating basic supplies, and making the children feel welcome. A school in our building had parents volunteer on the weekends, and we coached the kids in soccer. We all had a blast! Some of the students would run into the parents in the neighborhood, and they greeted each other fondly.

How do you build rapport with the families of your students who have recently arrived in the U.S.?

I conduct meetings with the parents when the children arrive and try to offer a special welcome breakfast to make them feel comfortable. Last year, we had flags from all their countries and special food that we thought they would enjoy. I also work with dual-language teachers to stay in contact and help families find language classes, tutoring, and basic supplies.

What’s one thing you’ve read that has made you a better educator?

Reading about the concept of the affective filter, which is an imaginary filter that becomes an impediment to learning another language. If the filter is high, students are stressed and self-conscious, and language learning is delayed. If it is low, they feel safe and take more risks, which helps with language acquisition.

So many adults tell me they hated learning Spanish or French in school, probably because they were so self-conscious. I constantly write grants to buy supplies and use secondhand chairs, lamps, and cabinets to ensure that my classroom has a cozy feel similar to a home. I make sure that students are comfortable and respect each other so that they learn with ease.

What’s the best advice you’ve ever received, and how have you put it into practice?

Seek out the educators who inspire you, watch them, sit in on their classes, and adjust.

Gabrielle Birkner is Chalkbeat’s features editor and fellowship director. Contact her at gbirkner@chalkbeat.org.