Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news organization covering public education in communities across America. Sign up for our free New York newsletter to keep up with NYC’s public schools.

New York City education officials plan to take a stronger hand in what curriculums educators can use in their classrooms, a move that could represent a major shift in how the nation’s largest school system approaches teaching and learning, Chalkbeat has learned.

The education department recently began laying the groundwork for superintendents to choose from three reading programs to use across their districts. It is also launching a standardized algebra program in many high schools. The plans have not been announced publicly, but were confirmed by four education department employees familiar with the city’s literacy efforts and multiple school leaders.

Principals historically have enjoyed enormous leeway to select curriculums. Proponents argue this allows schools to stay nimble and select materials appropriate to their specific student populations. But some experts, and even the city’s own schools chancellors, have argued that the approach can lead to a tangle of instructional practices that can vary widely in quality from classroom to classroom.

Now, officials are taking steps to rein in the city’s free-wheeling approach to curriculum. Beginning next school year, elementary schools in about half of the city’s 32 districts will be required to use one of three reading programs: Wit & Wisdom, from a company called Great Minds; Into Reading from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; or Expeditionary Learning, from EL Education.

By September 2024, city officials are expected to require all elementary schools to use one of those three options, according to an education department official familiar with the city’s plans.

Local superintendents will determine which curriculum is appropriate for their elementary schools, and some principals said they’ve already learned their superintendent’s selection. Separately, the city is rolling out a standardized algebra curriculum from Illustrative Mathematics at more than 150 high schools.

Still, the planned shift has already prompted pushback from some principals and their union. And some observers and education department officials wonder whether elements of the policy will ultimately change or be dialed back.

Standardized curriculums draw cheers and jeers

Schools Chancellor David Banks has made literacy a centerpiece of his administration and has demonstrated he’s willing to issue top-down curriculum directives.

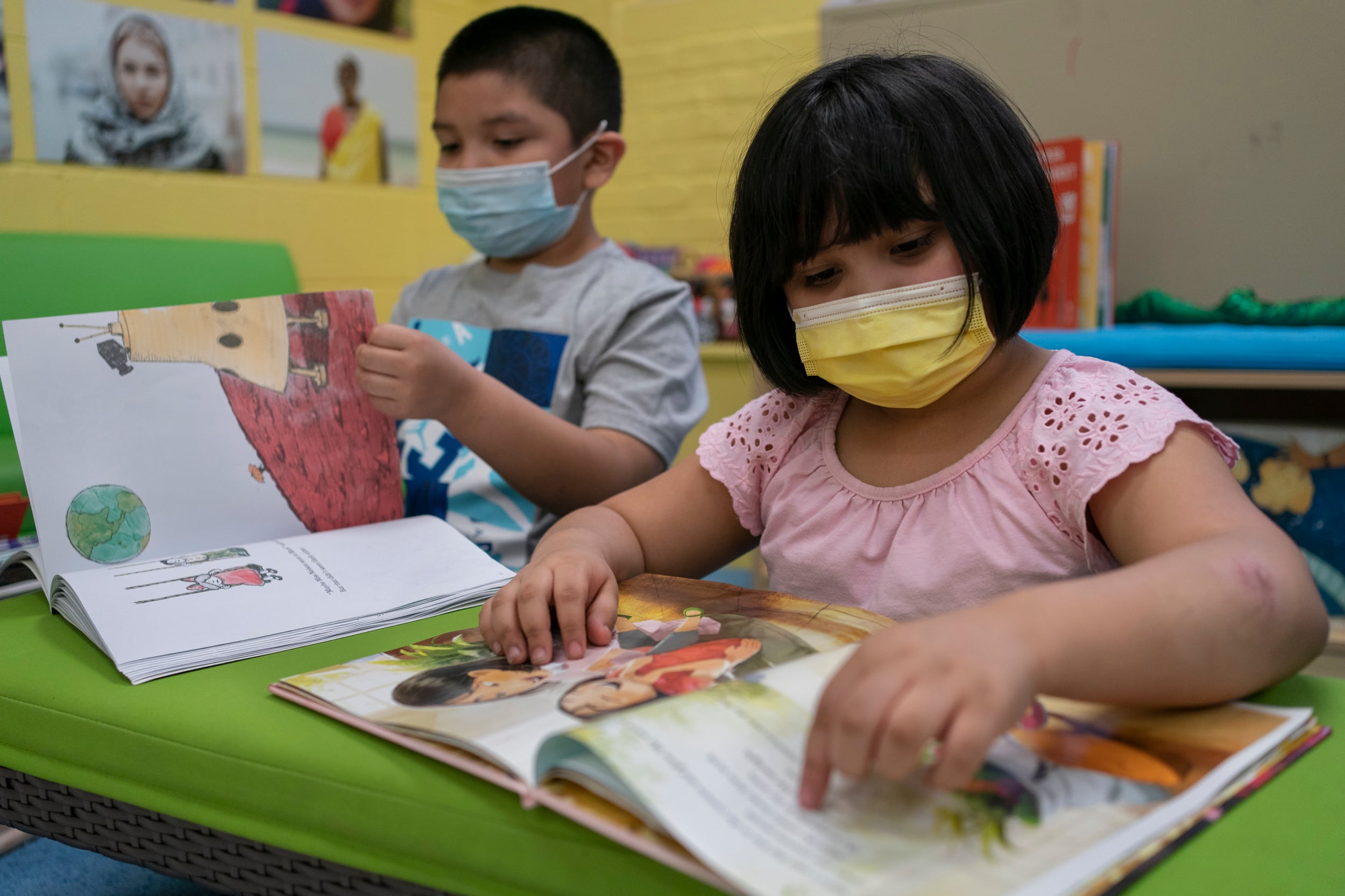

This year, Banks required all elementary schools to use an approved phonics curriculum, which schools often deploy in 30-minute blocks, on top of their reading curriculum. Now, many schools may be required to overhaul their fundamental approach to reading instruction, something Banks has repeatedly said would be necessary to address poor reading outcomes. Roughly half of students in grades 3-8 are not reading proficiently according to state tests.

School leaders and experts said the effort to standardize reading curriculums has some clear benefits. If there are fewer curriculums deployed across the city’s sprawling network of elementary schools, the education department can play a stronger role in making sure high-quality materials and training are available to more teachers. And when students or teachers switch schools, there’s less need for them to start from scratch with new materials.

“I’m in favor of more universality,” said Susan Neuman, a literacy expert at New York University and member of the education department’s Literacy Advisory Council. “It allows teachers to begin to collaborate more and develop a shared language. We haven’t had that.”

But the policy change is also raising alarms.

Some department administrators say there has been limited communication about how carefully those three curriculums were chosen. One of the curriculums, Into Reading, was criticized in a NYU report for not being culturally responsive. There have also been scarce details about how thousands of educators will be trained on new instructional approaches. Others noted that educators and families have had little opportunity to provide input.

One central education department administrator who spoke on condition of anonymity said more standardization isn’t bad in theory, but implementing a new curriculum that educators haven’t yet taught comes with challenges.

“It’s like telling a basketball coach to go coach football,” the administrator said. “I’m not sure there are the instructional supports needed to make it successful.”

The move would also require elementary schools to abandon a controversial curriculum called Units of Study, written by Lucy Calkins of Columbia University’s Teachers College, multiple department administrators said. Hundreds of elementary schools used that curriculum before the pandemic hit, according to an investigation by Chalkbeat and THE CITY.

A growing chorus of experts, including Banks, have dismissed the approach as ineffective for many young children, but some schools still believe they are getting results with it. Requiring schools to ditch Calkins’ curriculum would represent a dramatic change on many campuses and is likely to spark fierce resistance.

Henry Rubio, the president of the Council of School Supervisors & Administrators, said officials at his union have asked the education department whether they will provide exemptions from the curriculum mandate for schools that have a strong track record. They have not yet received a reply but plan to meet with department officials this week.

The union, which represents principals and other administrators, has also raised concerns about a looming deadline early next month for purchasing materials. Though multiple officials said they expect the education department to pay for new reading curriculum materials, rather than requiring principals to pay for it out of their budgets, some school leaders are not sure whether they’ll be able to continue using their existing curriculums next year and whether they should be preparing to buy materials, Rubio said.

“We believe it may already be too late for many schools to begin the preparation and training necessary to effectively launch new curriculum in the 2023-2024 school year,” union officials wrote in a newsletter to members last week. “CSA continues to escalate principals’ objections about superintendents mandating curriculum to the Chancellor’s team. As instructional leaders, principals know what is best for their school community.”

A spokesperson for the city’s teachers union did not reply to a request for comment.

Details on instructional changes remain scarce

Kevyn Bowles, principal of New Bridges Elementary School in Brooklyn, said his school currently uses the Units of Study curriculum created by Calkins and that elementary schools in his district would be required to transition to Into Reading. Calkins’ curriculum is popular in part because of training that schools can pay for from Teachers College that provides extensive coaching to educators.

“I do want to be fighting for schools to have curricular autonomy,” Bowles said. “Teachers put a lot of work into turning the program into actual plans and practice, and so switching to something new without understanding why is just going to be pretty globally unpopular.”

Other school leaders said a more standardized approach could hold some promise. Matt Brownstein, an assistant principal at P.S. 330 in Queens, said his school already uses Into Reading, which is also the curriculum that the superintendent there plans to mandate.

Although Brownstein acknowledged that the curriculum does not include many texts that reflect the experience of New York City’s diverse student body, he said he appreciates that it includes materials in Spanish, which the school uses in its dual-language program.

Brownstein noted that switching curriculums will be a disruptive process on some campuses, and he can see arguments for schools retaining more flexibility. But teachers are generally not given the resources they need to design quality curriculum materials, and providing a more standardized set of options could yield dividends, he said

“Considering all the variables, is it the right move?” he asked. “Probably.”

An education department spokesperson, Nathaniel Styer, did not respond to questions about the curriculum mandates, including the rationale for them, how many schools would be required to change, or how the city plans to train educators in time for the fall.

“We are currently engaging educators, parents, and advocates on how to address proficiency rates with urgency and best ensure that our students and our educators have what they need to succeed,” Styer wrote in an email. “We will have more to say after our engagement.”

Michael Elsen-Rooney contributed.

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.