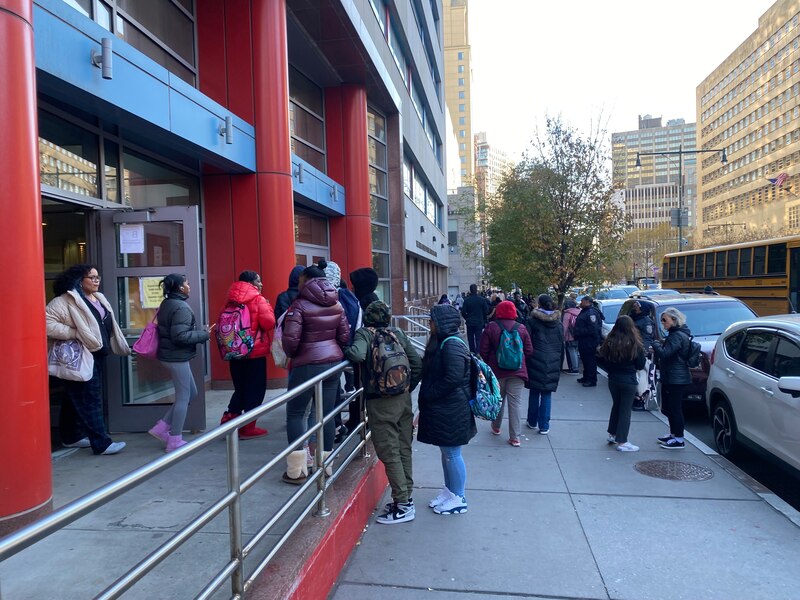

Jahya Williams often walks out of her Downtown Brooklyn high school at the end of the day to find a cluster of police officers monitoring dismissal. The 16-year-old feels uneasy at the sight.

“It makes me feel very intimidated,” said Jahya, a junior at Urban Assembly Institute of Math and Science for Young Women. “Having them in the school and right outside of the school is making me feel like a criminal.”

Jahya had seen conflicts between students bubbling up in the neighborhood after school, with some turning violent. Earlier this year, a 15-year-old student at a nearby charter school was shot and killed around 1:30 p.m. in a park just blocks away, a tragedy that reverberated across a neighborhood packed with middle and high schools.

But Jahya had never gotten a chance to ask anyone at the NYPD directly about the police presence outside her school or share how it made her feel — until recently.

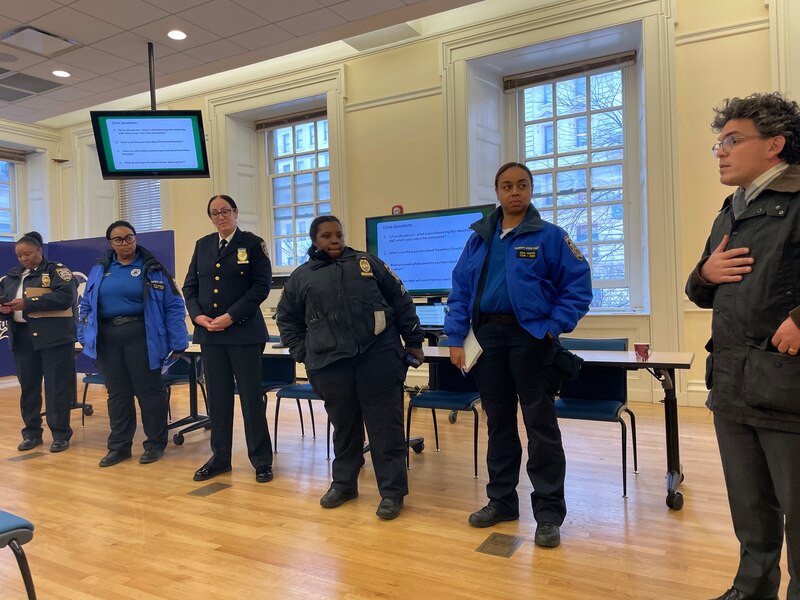

Jahya is one member of a new working group, launched by City Council Member Lincoln Restler, that brings together student and staff representatives from nine schools in the area, along with police, school safety agents, and civic leaders to talk about how to make Downtown Brooklyn safer.

For Jahya, the first meeting of the task force last month was eye opening.

“Stuff like that is extremely helpful because the cops said certain things I’ve never heard and we said things they’ve never heard,” she said.

“Just seeing their [NYPD’s] perspective on how they see us … all they’re seeing is the little rivalries, everything that happens outside of school, and then we clash,” she said. “What we see is you all … getting in the way.”

Participants acknowledged that no easy answers emerged from the first meeting and said it will take sustained work to begin to break down deep-seated mistrust between students and police.

But school staffers said it was a positive step to put all the campuses in the area in direct communication, since many of the conflicts that break out involve students from multiple schools.

“We have so many campuses in such a small radius, all the kids filter into a relatively small area and mix at one time,” said Annie Annunziato, an assistant principal at Urban Assembly Institute of Math and Science for Young Women. “The idea was: Let’s bring everyone together and open the lines of communication.”

A tragic death is a call to action

Conflicts have bubbled up after school for years in Downtown Brooklyn, a bustling commercial hub with a high density of schools.

But students, staff, and lawmakers said safety concerns have escalated in the wake of the pandemic.

“It really has changed,” said Anayasia Bass-Williams, a 16-year-old junior at Institute of Math and Science, who’s been going to school in the neighborhood since sixth grade. “Before the pandemic it wasn’t as heavy. Now it’s extremely heavy.”

Students described a rise in frightening interactions with mentally ill people on the streets, more open selling and using of drugs, and an uptick in conflicts between students from neighboring schools converging in popular spots like a local Burger King and the subway station.

“Once everybody’s outside, it’s a whole lot of energies mixed, personalities, groups,” said one student at the Institute of Math and Science, whose name Chalkbeat is not disclosing to protect her privacy. “It’s chaotic.”

Restler, the council member for Downtown Brooklyn, said he was shaken by the death of 15-year-old Unique Smith, a student at Brooklyn Lab Charter school who was killed in Mclaughlin Park just after getting out of his first day of school.

“Never had we had anything like the horrible tragedy where Unique Smith was lost to gun violence at just 15,” Restler said.

Restler convened a meeting of administrators from the nine schools in the area to coordinate. It was during that first brainstorming session that Annunziato suggested bringing students into the conversation.

That was “so right and smart,” Restler said. “Ask the people closest to the problem … how we can fix it.”

Students debate the role of police

At the center of the conversation about making Downtown Brooklyn safer is the question of what role the police should play.

Five students who participated in the first meeting of the working group told Chalkbeat that they find the NYPD’s presence in the area often ineffective and sometimes harmful.

“Every single fight I’ve been in Downtown, they’ve never intervened, not once,” said one Institute of Math and Science student. “They do nothing. It’s the bystanders or pedestrians breaking up the fights.”

The teens said that when police do get involved in conflicts between students, it often feels overly harsh.

“They pour oil on the fire,” said Fredlove Deshommes, a 16-year-old sophomore at Urban Assembly School for Law and Justice, which shares a building with the Institute of Math and Science.

Some students said when police come, they often end up unjustly or arbitrarily arresting students.

Annunziato said police officers at the first meeting of the task force explained that it can be difficult in the heat of the moment to tell which students are involved in the altercation and which are spectators, particularly when students are tightly packed in to record the fight on their phones.

“When there’s a chaotic situation like a fight, it’s hard to understand who’s involved or not,” Annunziato said. “One wrong bump can lead to an arrest, and I’ve seen that.”

An NYPD spokesperson said the police department and school safety division “have ongoing open dialogue with child advocacy groups, students and other stakeholders in order to respond to concerns, while maintaining a balance between the safety of the entire school community and the importance of not criminalizing our youth.”

The spokesperson pointed to 2019 changes to the memorandum of understanding between the NYPD and education department meant to reduce in-school arrests and empower school staff to handle “minor student transgressions, without involving formal criminal proceedings.”

One school safety agent at a Downtown Brooklyn high school, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said the “large population” of students “thank us” when they see NYPD youth officers posted outside of school during dismissal.

“They knew it wasn’t being done to hurt them or stop them from being a kid,” the safety agent said. “But the kids doing their nonsense think they’re being targeted. That’s absolutely not the case.”

Race underlies the discussion about police and student safety. The vast majority of students at the public and charter schools in the neighborhood are Black and Latino – and students suspect that plays an important role in how they’re treated.

“I bet you if there were two white kids fighting, they would be like ‘stop it,’” said Anayasia.

“For us, it’s handcuff, handcuff,” said Jahya.

Searching for solutions outside of police

Restler said one of the ongoing priorities for the task force in the coming meetings will be brainstorming solutions that don’t involve the police.

“I would like to see us pool resources across the schools to bring in nonprofit organizations that could provide a supervisory presence in some of the key locations,” Restler said.

Students consistently pointed to the need for larger-scale citywide plans to provide support and services for severely mentally ill people they encounter on their commutes or outside of school.

It’s those encounters that have led many teens to start carrying pepper spray, tasers and other self-protection tools on their way to and from school, students said – devices that can be confiscated by school safety agents and categorized as “weapons” or “dangerous items” by the NYPD.

Last year saw an explosion in the number of such items turning up at schools, and the trend has continued this year, with the number more than doubling from 790 from July through October of last year to 1,510 during the same period this year, according to NYPD data.

The biggest jump came in a category listed as “other weapons/dangerous items.” Police didn’t specify which items fit in that category, but it presumably includes pepper spray, which is confiscated by school safety agents, and not listed as a separate category.

The Downtown Brooklyn school safety agent who spoke on the condition of anonymity said she sympathizes with students who want to protect themselves on their commutes.

“It’s a lot for these kids to deal with … I get it we’re living in times with a lot of people that have mental health issues,” the safety agent said. “But walking around with a weapon is not the right thing to do.” The safety agent advises students to travel in groups, hide their electronics, and keep their headphones off during commutes.

Daysha Williams, a 16-year-old junior at the Urban Assembly School for Law and Justice, said it’s frustrating that so much of the onus for keeping students safe gets pushed onto the students themselves.

“I just feel like I shouldn’t have to walk with five million people or go down this street because I feel unsafe,” she said. “I feel like that’s placing the problem on the victim instead of addressing the root of the issue.”

Michael Elsen-Rooney is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Michael at melsen-rooney@chalkbeat.org.