Thousands of New York City teachers returned to their school buildings on Tuesday, the first step in a high-stakes test of whether the nation’s largest school system can safely reopen school buildings without a resurgence of the coronavirus.

Districts across the country are watching closely to see if Mayor Bill de Blasio’s plan to reopen school buildings for in-person learning after an 11-day delay will become a roadmap for them to follow or a cautionary tale of the dangers of in-person schooling. New York City is among the only large school districts attempting to bring students back for in-person learning to start the school year.

Many of the educators responsible for carrying out that plan returned to their buildings Tuesday to reconstruct their classrooms in light of new health rules, participate in workshops, and get ready for a school year unlike any they’ve ever faced. Some said they’re eager to see their students in person and believe that the educational benefits of in-person learning are worth the health risks. Others say they are worried for the health of their school communities and believe the city’s safety and instructional plans fall short.

“I think that it’s important to have an in-person option,” said Stephanie Edmonds, a teacher at the Bronx High School for Law and Community Service. Though she acknowledges there are health risks to reopening, she believes there are also enormous educational and economic downsides to keeping school buildings closed.

“There’s a lot of kids who just have a really hard time not having that physical space,” she said. “Even for myself, getting up and doing that structure [this morning] — it felt good.”

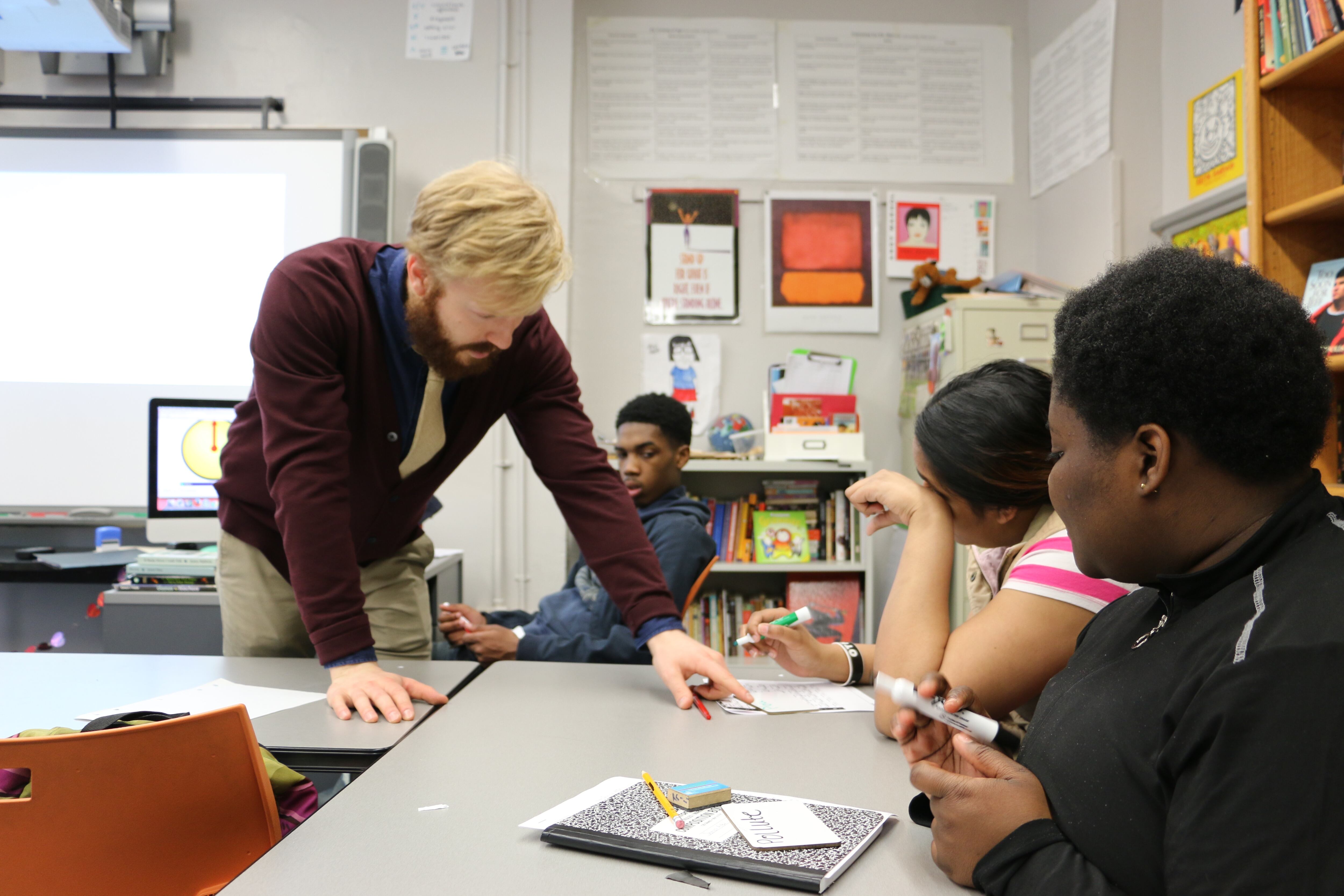

Teachers began to get a sense of just how different this school year will feel, as normal routines and classroom practices are no longer viable. Eric Wilson, a teacher at Brooklyn Frontiers High School, began his day by filling out a safety questionnaire online about whether he has experienced any coronavirus symptoms before setting off on a 20-minute bike ride to his Downtown Brooklyn school to avoid contact with people on public transportation.

The classrooms in his school are essentially frozen in time from March, when buildings abruptly shut down. Now, he’s working with his colleagues to strip posters from the walls, get rid of bean bag chairs, and remove a stuffed tiger (the school’s mascot) so that the rooms can be sprayed down and cleaned each evening. He said the teachers had to resist the temptation to congregate in the hallways and catch up with one another.

We’re “just trying to make these comfy classrooms into a place that’s a sparse and sterile place,” he said. “No matter how much we want to, we’re not going back to school the way it was.”

Many teachers spent their days on Tuesday in meetings reviewing safety procedures and discussing how to construct two simultaneous versions of school. Most students will be attending in-person one to three days a week and learning from home the rest of the time, while 39% of students have so far opted for fully virtual learning.

Wilson and several other teachers said that beginning to plan their lessons is daunting due to outstanding questions about teacher schedules and how they will balance in-person and remote students — questions that many schools are still racing to answer. “It still feels like an incomplete picture, and I don’t really know what I’m preparing for,” Wilson said.

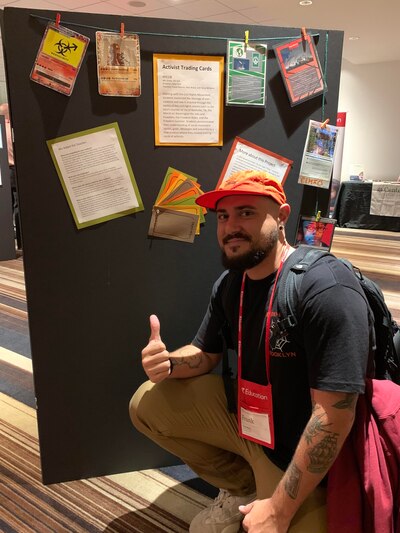

Frank Marino, a humanities teacher at M.S. 839 in Brooklyn, said he spent part of the day discussing new all-school themes designed to build community. The themes center on identity. Every student will read “New Kid,” for instance, a graphic novel about a student from Washington Heights who is one of the only students of color at his private school. Students will also create self-portrait collages that convey how their lives have changed over the last six months and what their hopes and goals are.

“This is a way for us to stay connected,” Marino said. “We threw out what was not essential and kept what is joyful.”

Marino participated in those meetings remotely because he is one of almost 16,000 teachers — or roughly 21% — who have been granted permission to work from home because of health conditions that make them more vulnerable to the virus. Some schools are already dealing with the awkwardness of some teachers being allowed to work remotely and showing up on Zoom calls without masks while their colleagues report to buildings and are participating in the same meetings while wearing masks and adhering to social distancing rules.

Melissa Dorcemus, a teacher at Manhattan’s New Design High School who helped craft the school’s reopening strategy, said the school set up a meeting for the 11 teachers who will be remote only to help deal with feelings of guilt and other emotions. “In general people are feeling this weird tension about not being there for their colleagues,” said Dorcemus, who received an accommodation because she is pregnant. “The main goal today is to make people feel comfortable.”

At many schools, questions about the safety of bringing teachers back in person weighed heavily, concerns that contributed to the mayor’s decision to postpone in-person learning for students until Sept. 21. One central safety concern that has emerged in recent weeks is the status of ventilation systems, as the coronavirus is believed to spread largely through droplets in the air. City officials released ventilation reports for schools across the city and said 21 could not open yet due to inadequate ventilation.

Nate, a high school teacher who requested only his first name be used in order to speak freely about his south Brooklyn school, saw several staffers working in their classrooms together had removed their masks during their 8:30 a.m. Zoom faculty meeting.

“To me it was extremely disappointing, and the kids will follow the example if there is a strict culture,” he said. “If teachers are flagrant with it, kids are definitely going to be.”

Jillian Gruber, who teaches students with autism at a Queens District 75 program, which serves children with the most significant disabilities, hated remote learning and is thrilled to return to her building. Gruber could have applied to work from home because she has high blood pressure and liver disease, but feared losing the new class structure she’s wanted for six years. (She will teach eight students in third to fifth grade this year instead of six K-2 students).

But during her first visit back to her building since March, she was discouraged by safety procedures on display. She has not yet received any personal protective equipment for her class. Her temperature was not checked until 20 minutes after she entered the school building, which was also when someone checked to see if she’d filled out the required health screening survey.

She’s hoping to be trained later this week on how to calm students who may get aggressive or attempt to run while maintaining social distancing.

Beyond safety, some of the remaining unknowns around how classes will be staffed were front of mind for many teachers. The city’s “blended” model demands separate teachers for in person and remote learning, which has created a massive staffing crunch as the city faces a $9 billion budget deficit and potential cuts from the state. Mayor de Blasio has promised that “thousands” of teachers will be made available to schools, but final details about how this will be achieved remain unknown.

On Tuesday, city officials lifted hiring freezes across a wide range of license areas, though many principals may struggle to pay for these extra positions because of smaller school budgets this year. The department is trying to identify staff who work in centrally funded programs who can instead teach at specific schools this year, though it’s unclear which programs those are.

Nate said his school spent Tuesday morning reviewing changes to Google Classroom, going over staff announcements, then breaking into separate meetings with their departments to discuss student enrollment and instruction in the fall. Teachers were given the rest of the day to plan their classes, but that was tough to do without key details, such as whether the school will be able to fill an estimated 30-40 staffing holes, he said.

While he’s knows which courses he’ll teach, he’s received no clarity on how he and his two co-teachers, who will all be in the building five days a week, should instruct and plan for their students on the days they are learning from home.

“On one hand it was really good to see everybody — good to see coworkers and colleagues again,” he said. “On the other hand, all the worries I had [before] have only increased.”