When Nicole Lent’s principal asked her to give up teaching a single class of students in favor of teaching math across her Bronx elementary school, she was skeptical.

Would her relationships with students suffer? Would students seamlessly adjust to learning from a larger group of teachers with different routines? And most of all, would P.S. 294 students do better at math?

More than two years into the shift, part of a sweeping city experiment in overhauling how elementary school students are taught math, Lent says she is confident the changes are paying off. So, too, are city officials who are expanding the initiative.

But two new pieces of research suggest that the city’s approach — a crucial piece of its plan to get all students ready for algebra in middle school — might be misguided. The studies, which examine “departmentalization” efforts in other places, raise questions about whether the rapidly expanding city program that encourages schools to departmentalize fifth-grade math could be doing more harm than good.

The theory behind departmentalization is that even in elementary school, students should benefit from having math teachers who know their subject and have deep experience teaching it.

Its advocates argue that elementary school students especially lose out by getting math instruction from classroom teachers who not only have no specific math expertise, but also often do not like math themselves. Specialization benefits students in middle and high schools, they argue, and in order to get students on track for more complex math as they age, they need a solid foundation when they are young.

The argument resonated with city officials three years ago when they launched an “Algebra for All” initiative. This year, 139 city elementary schools are adopting the departmental approach, almost twice as many as a year ago.

The expansion comes as accumulating research casts doubt on the approach. A study recently published by the peer-reviewed American Economic Review found that students perform worse on both high- and low-stakes tests after elementary school teachers specialized in subjects including math.

To measure the effects of reconfiguring elementary school teaching, Roland Fryer, an economics professor at Harvard who has studied schools extensively, randomly assigned 23 Houston elementary schools to departmentalize instruction in math, science, social studies, and reading.

At those schools, principals assigned teachers to teach what observations and statistical measures suggested were their strongest subjects. But after two years of specialized instruction, students lost over a month of learning compared with their peers who attended schools that did not make the changes. And students were worse off in other ways, too.

“Sorting teachers in a way that allows them to teach a subset of subjects of relative strength has, if anything, negative impacts on test scores, negative impacts on attendance, and increases suspensions due to ill-advised behavior,” Fryer wrote. “Moreover, these impacts seem particularly stark for students with special needs and students taught by younger teachers.”

The findings aren’t broken out into each subject, but fifth-graders with specialized teachers generally learned less than their peers across multiple subjects (though the negative effect was somewhat smaller).

The study does not explain exactly why teacher specialization hurt student learning, but Fryer suggests teachers could have a harder time tailoring their instruction to each student. Though specialized educators teach fewer subjects, they often teach significantly more students — making it more difficult to build relationships and quickly help students who get tripped up.

A second recent study based on statewide data from North Carolina also points to the potential pitfalls of specialization. That research, which has not been formally peer reviewed, looked at teachers who transitioned from being general classroom teachers to specialists and compared the effect on student test scores.

While the researchers found some positive effects in science, specialization hurt student learning in many subjects and grade levels — including fifth grade math.

“This is the second study — in different locations and with different research designs — to show some negative results for subject-area specialization,” write Kevin Bastian, a researcher at the University of North Carolina, and Kevin Fortner, of Georgia State University. “It is fair to conclude that specialization is not yet leading to its theorized payoff.”

New York City officials say that’s not true here. And they argue that the research doesn’t directly apply to the city’s efforts to overhaul math teaching.

“Schools departmentalizing through Algebra for All choose to enter the program and receive intensive and ongoing support,” education department spokesman Will Mantell wrote in an email. “This is not the case for the randomized Houston experiment.”

City officials instead cite a different study by a professor at the University of Washington who conducted a simulation that shows teacher specialization should boost student learning. That study’s author, Dan Goldhaber, said his findings are purely theoretical. And while he doesn’t think the city should abandon its approach, Fryer’s study “convinces me that we should be cautious.”

The details of how the model is implemented in different schools and districts matter, including the level of training and support that come with it. Some schools may not be able to minimize disruptions associated with having younger students shuttle between classrooms more frequently, for example, instead of staying with one classroom teacher.

“It’s quite possible that the mechanics of the way you pull off teacher specialization are quite important in determining the results,” Goldhaber said.

Lent, who specializes in math at P.S. 294, acknowledged there have been some bumps in her school’s departmentalization efforts. She went from teaching 32 students she had followed over consecutive years — a practice called “looping” that can boost student learning — to teaching 64 students.

“We dealt with our fair share of behavioral issues,” she acknowledged, partly because it took time to build relationships with a wider group of students. But once her students adapted to the change, “they took off,” she said.

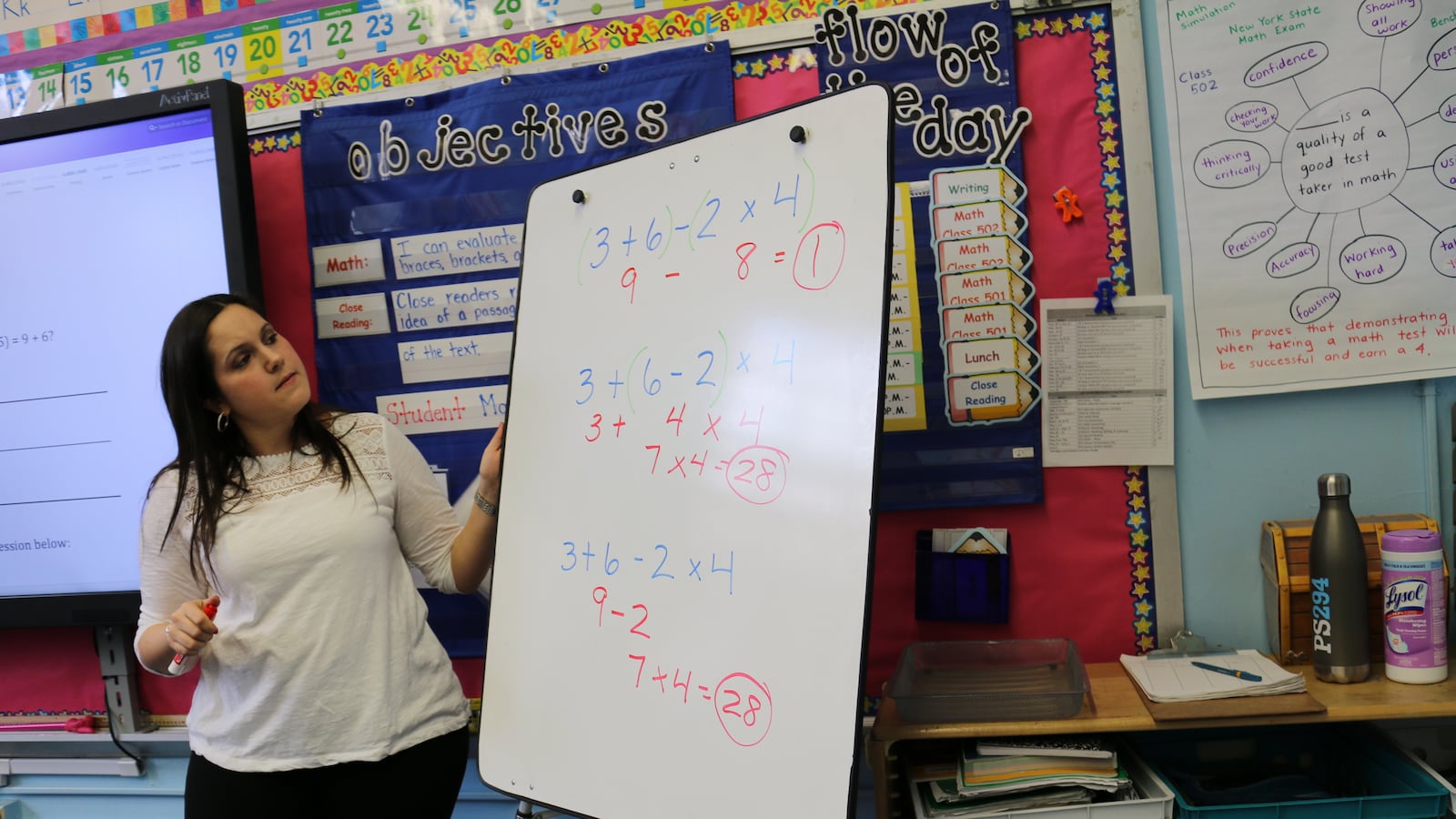

The school has benefited from extra training and resources provided by the city’s Algebra for All program — which has helped the school overhaul its math instruction. Teachers now facilitate conversations about math concepts, instead of focusing on teaching students procedures to arrive at correct answers.

But it’s unclear whether the city’s efforts to departmentalize fifth grade math will pay off across the board, and the education department has not asked outside researchers to evaluate their efforts. City officials said they would look at student performance data and surveys, but some researchers said that won’t offer a full picture of the program’s effects.

“It always seems wise to evaluate any major initiative,” Jonah Rockoff, an economics professor at Columbia, wrote in an email. “Without a more formal evaluation design, like the Fryer experiment, it will be difficult to make strong conclusions.”