New York City is planning to end its program to administer weekly coronavirus tests to a random sample of students, Chalkbeat has learned, removing one of the last standing campus COVID safety measures.

The decision to discontinue on-site PCR testing after summer school ends was communicated internally last month, a source with knowledge of the program said.

“The city decided it was no longer necessary,” the source said, noting that a specific rationale wasn’t provided. Chalkbeat also reviewed communications that suggest the program is ending.

A City Hall spokesperson denied that the city’s plans for the fall have been finalized, but did not directly dispute that the city is moving away from in-school PCR testing.

“To be clear, no final decisions have been announced about testing in schools in the coming year,” wrote Amaris Cockfield, a mayoral spokesperson. “Anyone saying otherwise is speaking with absolutely no authority. We are still finalizing plans to keep schools safe and open this year, and will communicate our plan with families when there is an actual decision.”

One of the labs involved with the in-school testing program confirmed their contract is ending after this story initially published.

“NYC hasn’t renewed testing contracts with any of the providers it used the last two years,” wrote Nicole Borsje, a spokesperson for Fulgent Genetics, one of the four companies that helped run the random PCR testing program.

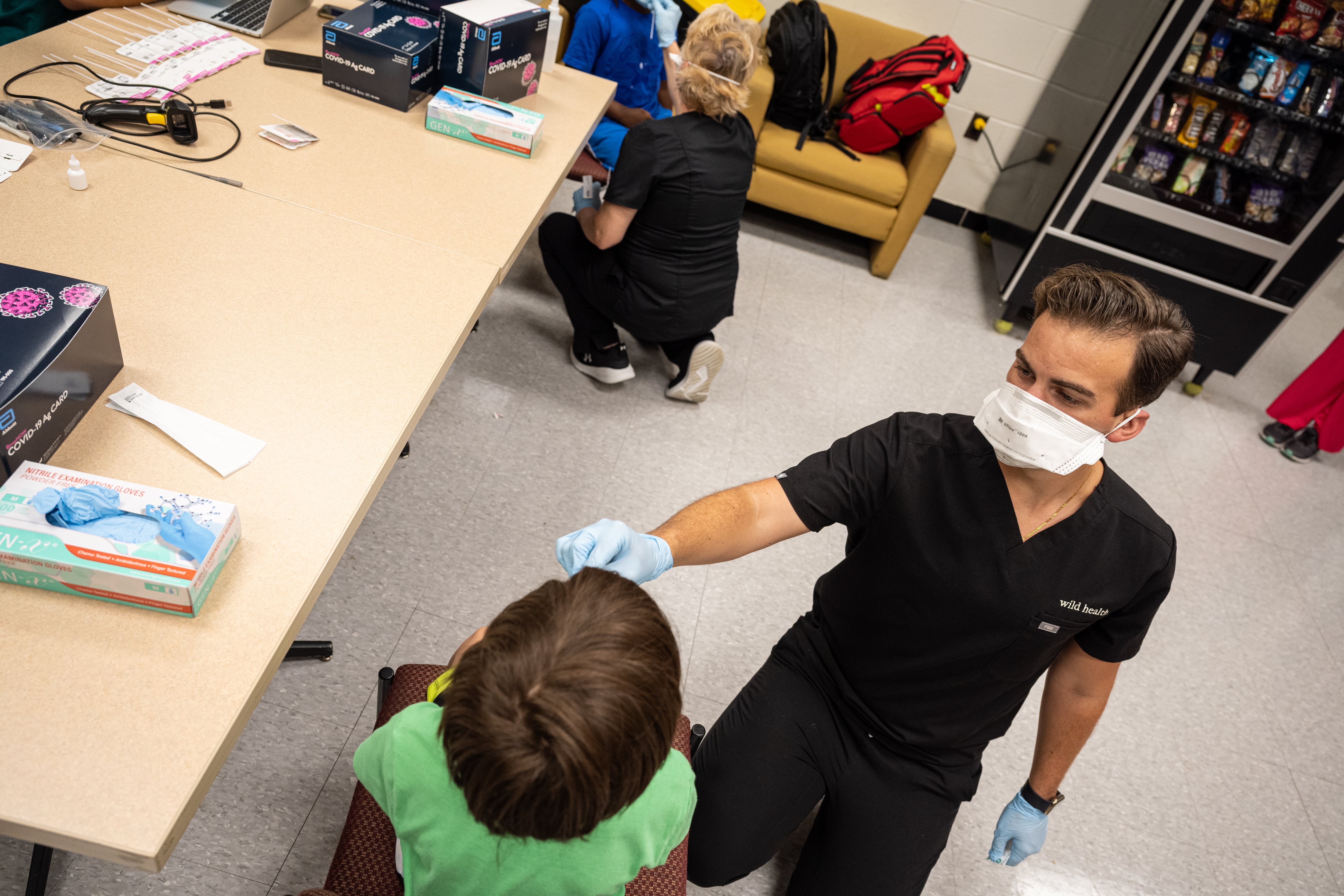

Launched in fall 2020 as the city reopened school buildings for the first time, the program aimed to detect large outbreaks in schools and offer big-picture data about whether mitigation measures such as masks and social distancing were keeping the virus in check.

But the pandemic’s course — and the city’s responses to it — has changed significantly since the testing program was first conceived. Some public health experts had previously questioned whether the testing program was worth the expense at upwards of $30 million a month. (The program was initially supported by a $251 million federal grant though city officials have not revealed the program’s total cost.)

City officials have not yet shared what COVID safety measures will be in place next school year or what the city’s testing strategy might be. Last school year, schools initially sent home rapid kits to students and staff when they were exposed to someone in their classroom who tested positive, and later sent them home to everyone as a preventive measure. The goal was to identify cases when someone wasn’t feeling well, as well as to help clear them to return to buildings faster.

Dr. Jay Varma, a top health advisor to former Mayor Bill de Blasio who designed the in-school testing program, said that it could be appropriate to end the testing program as long as the city supplies rapid tests. Gov. Kathy Hochul has indicated the state is planning to make millions of rapid tests available to schools this fall.

“If every kid is going to get a supply of them weekly, then I think the city does not need to continue routine PCR screening,” Varma wrote in a message to Chalkbeat.

The city’s teachers union has been a major advocate for expanding the in-school PCR program, which allowed up to 10% of staff to be tested weekly by the end of last school year, though educators said that in practice the testing companies sometimes declined to test them. The source familiar with the city’s decision said the in-school PCR testing would no longer be available to staff.

Alison Gendar, a spokesperson for the United Federation of Teachers, said the change needed to be negotiated with the union.

“The Department of Education cannot unilaterally change COVID protocols without engaging the UFT and the other unions representing school employees,” she wrote. “Those conversations have not taken place.”

Mayor Eric Adams, who has pushed for the city to return to pre-pandemic life, rolled back other school safety measures last year, including universal masking and social distancing rules. And some experts argued the testing program may not be delivering many concrete benefits.

The city did not clearly explain how it was using the testing data to drive big-picture policy decisions such as whether to institute universal masking. Officials generally stopped closing classrooms or school buildings when positive cases arose, though students and staff were still required to stay home if they tested positive.

There were also questions about the quality of the data. Although the program’s goal was to sample a random group of students, that’s not how it worked in practice. The program involved pulling students out of class, sometimes for up to 30 minutes — but the majority of students did not consent to testing, which left some children getting swabbed repeatedly. By the end of last school year, the city was aiming to test at least 10% of students each week.

Still other experts previously said the program may also provide some peace of mind to parents, educators, and students that the virus is not running rampant in school buildings. The lab tests are generally more accurate than rapid tests, though they take longer to return results, making them less useful as a strategy for quickly isolating students.

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.