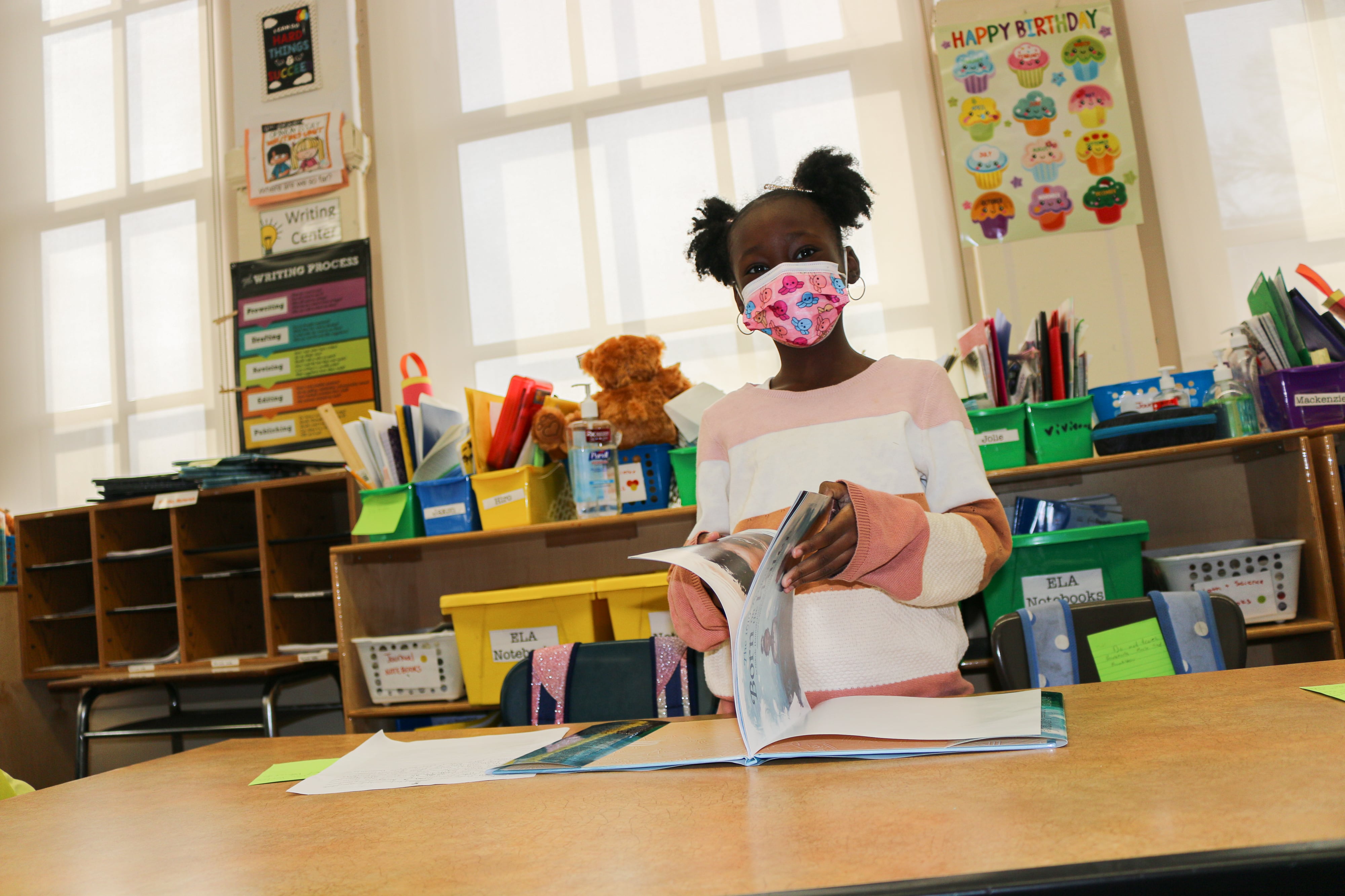

At a time when states across the country are restricting how America’s history is taught, teachers at P.S. 125 Ralph Bunche in Harlem spent three weeks guiding their students through “The 1619 Project: Born on the Water.”

Students wrote poems, drew self-portraits and visited with the authors, acclaimed children’s book writer Renée Watson and Nikole Hannah-Jones, an award-winning journalist.

The fictional children’s book was adapted from the New York Times’ 1619 Project, which was created by Hannah-Jones to reexamine the legacy of slavery and the contributions of Black people in America. Hannah-Jones earned the Pulitzer Prize for Commentary for its opening peice, and the project has been adapted into a book and school curriculum.

The 1619 Project also ignited a conservative backlash that continues to reverberate in classrooms since it was first published in 2019. At least 27 states have tried to ban teaching the project specifically, or broader discussions of race and racism in America. Former President Trump even threatened to defund schools that used the project.

Last week, Hannah-Jones and Watson met with students at P.S. 125 for the start of Black History Month and to hear how the children responded to their work.

“It taught me a lot,” said Robyn Starks-Ragler, 9, a fourth grader. “I know where I come from.”

“It was kind of special to me because it made me feel like I wasn’t alone,” said Keisha Genestin, 10, a fifth grader.

“I liked the book because maybe people didn’t know the history of Black people,” said Shima Vonjoo, 9, a fourth grader. “Maybe they didn’t know it didn’t start with slavery.”

The children’s book, which includes artwork by Nikkolas Smith, is a series of poems that tells the story of Black people from before slave ships arrived in Virgina. It includes the history of slavery but also the resilience and accomplishments of Black Americans.

In New York City, where schools are among the most segregated in the nation, P.S. 125 stands out for its diversity. Perched at the top of Morningside Park, about a third of students are Black and almost 40% are Latino, while 19% are white and 5% are Asian American.

Students spent the morning reading poems to Watson and Hannah-Jones, which included the refrain “I am from,” and talked about eating meals of black beans and rice, vacations spent lakeside with grandparents, and growing up in a small apartment. The students asked questions about how the two became authors, tips for writing, and what inspired them to pen the book.

“We’re lucky to be in a city that is not trying to restrict what our children can learn about Black history and about Black culture,” Hannah-Jones said in an interview at the school. “You can see from the dialogue that these students were able to engage in, there’s nothing to be afraid of, that our children are capable of having complex thoughts and dealing with histories that are tough, and feeling empowered by that.”

The event was organized by Behind the Book, a nonprofit that partners with schools to bring literacy programs to schools. The organization donated 135 copies of “The 1619 Project: Born on the Water” to students at P.S. 125.

Before students lined up to have their book signed by the authors, Hannah-Jones posed her own question. She asked the fourth and fifth graders what they learned, opening up a frank discussion about race.

“Did you face any discrimination challenges in your childhood?” Chace Thomas, a 10-year-old fifth grader asked.

The classroom went silent for a beat until Watson replied: “Absolutely.”

“Listen, we both grew up in communities where a lot of people didn’t necessarily think that children like us should be successful, that children like us could be smart. I certainly faced that in my own childhood, people doubting my capabilities because I came from low-income communities, because I was a young, Black girl,” Hannah-Jones said. “The most important thing is: You cannot control how anyone is going to see you, but you can control your own response to how they see you. And so every time someone thought that I couldn’t do something, I was determined in my head to prove them wrong.”

She assured the students: “You will prove society wrong if people doubt you or discriminate against you.”

Principal Yael Leopold called the authors’ visit “perfect timing.”

She became principal only a few months ago, when the project was already in motion. But Leopold was on board, noting her own copy of “The 1619 Project: Born on the Water” was one of the first things she unpacked in her new office. It sits on a shelf above her desk.

She knows the climate is difficult when it comes to leading classroom discussions on the themes of the book, and she said she was nervous about what the school community’s response might be when she hung a “Black Lives Matter” sign on the office door. In Brooklyn, parents at an elementary school say flags supporting Black Lives Matter and the LGBTQ community have been repeatedly torn down, and New York is considering its own ban of the 1619 Project in college classrooms.

But Leopold called it “necessary” to not only discuss race and racism, but to also make sure that students from diverse backgrounds are represented in what’s taught and in the murals that line the school’s walls. A former administrator for the city’s early childhood programs, she noted research that children begin to notice skin color and race as early as prekindergarten.

“Our children are always ready,” she said. “They’re willing to have the conversations. They’re wanting to have the conversations, and it’s us, as the adults, who have to be comfortable.”

Amy Scoufaras, a third-grade teacher who is white, admitted that it was intimidating to lead her class through the book. Her advice to other teachers who might have similar reservations was to just get started. She said she has seen the difference it made for her students.

“We found the book really lifted some students and their perception of themselves,” she said. “We really learned from students who don’t normally talk – they talked and they shared.”