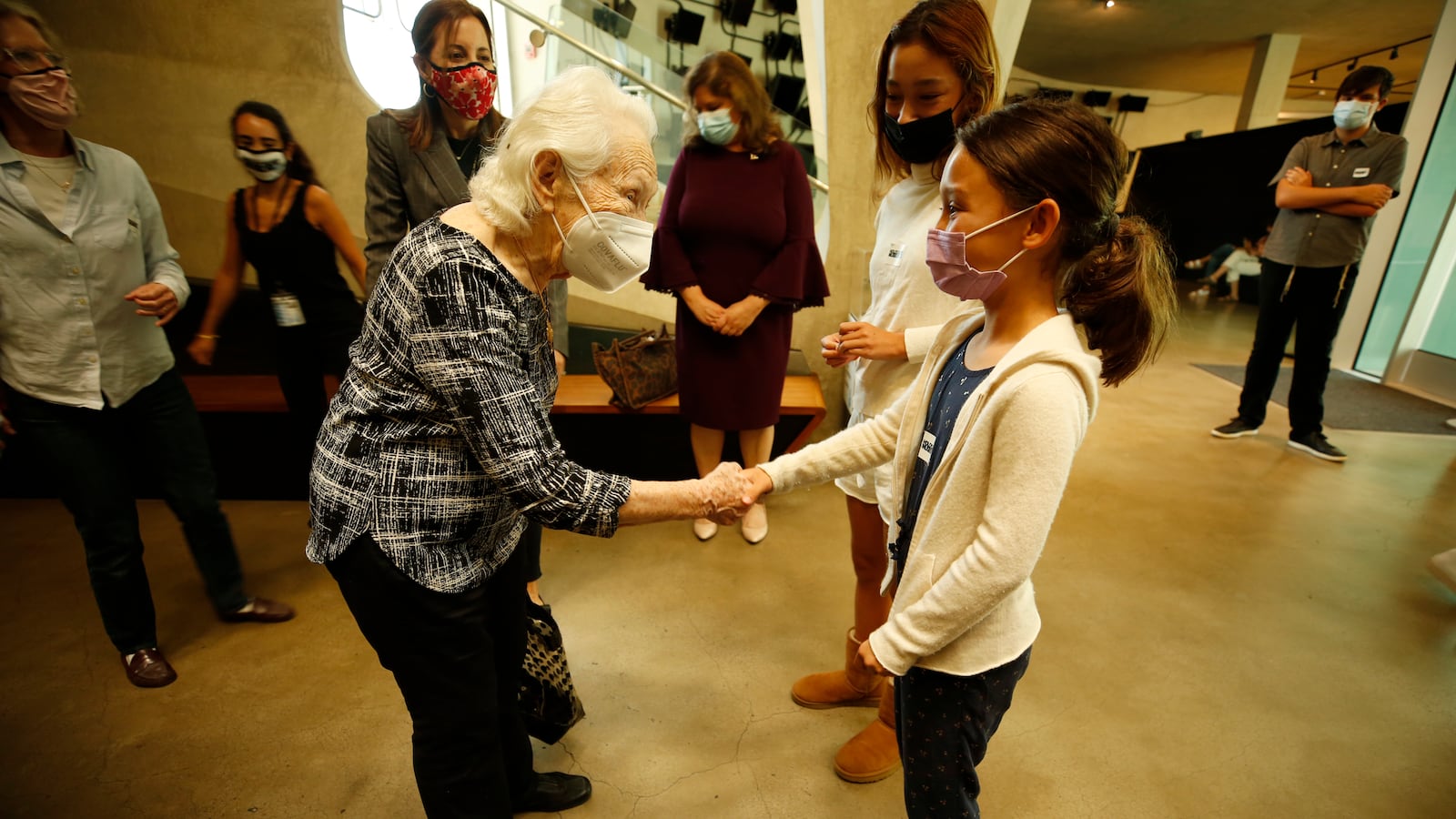

At the height of the pandemic, when schools were frequently closed and field trips paused, I missed meeting with students in person. I’m acutely aware that with each passing year, there are fewer opportunities for students to experience the firsthand testimony of a Holocaust survivor.

My generation is aging. Those of us who were children during the Holocaust are today grandparents and great-grandparents. Many are ailing. Many have already passed away.

Teachers across the country should take advantage of the increasingly precious opportunity to put students in touch with a survivor. In New York, talks can be arranged through the city’s Holocaust memorial museum, where I’m a member of the Speakers Bureau.

As we confront Holocaust denialism, resurgent antisemitism, and renewed debates about how the Holocaust is taught in schools, we must prioritize these learning opportunities for our young people, in person when it is possible and online when it is not.

Primary sources, like documents on display at the museum or testimony from Holocaust survivors like myself, provide irrefutable evidence of this history with an emotional immediacy that ensures it is never forgotten.

Back when I was a classroom teacher in Brooklyn, I served as a primary source for my own students. Seeing the reaction on their faces, and particularly in their eyes, showed me the impact of sharing my lived experience.

They were feeling what I was describing — my hunger, my fear, and my hope. I am ever so grateful for those classroom experiences, which inspired me to continue sharing my testimony through the decades.

As we confront Holocaust denialism, resurgent antisemitism, and renewed debates about how the Holocaust is taught in schools, we must prioritize these learning opportunities.

When I meet with students today, I tell them about my experience as a Jewish child in Poland, kicked out of school and driven into hiding from the Nazis. Fearful of deportation to the death camps, I lived outdoors in the fields at first, sleeping secretively in hay barrels, and then spent two difficult and traumatic years in the cramped attic of a Polish Catholic family willing to hide me and 14 members of my family.

I share my story with students, and have helped develop Holocaust curriculum for the classroom, knowing that young people want to understand their world and are more than capable of confronting difficult truths.

What I most want them to know is this: We are all equal. We are more than our political divisions and religious identifications, more than our nationalities, and more than our different skin colors. We share a human identity, and we each deserve respect. We all love, and we all want to be loved.

Once you understand that, the world softens. It becomes less harsh. We can choose to spare others from suffering and to make a better world through our actions. But to fully appreciate the power of that choice, students must reckon with the dangers of inaction, apathy, and bigotry.

As teachers plan their activities for this new school year, I encourage a class visit to the museum’s newly opened exhibition, The Holocaust: What Hate Can Do.

The exhibition is an eye-opener on the long history of antisemitism with important lessons for today’s youth. Just this fall, Governor Hochul visited the Museum, where she signed new legislation to ensure Holocaust education is properly taught in our schools.

At the signing, she said, “I don’t want the citizens of my state to live in fear,” and insisted that education is a powerful tool in the fight against bigotry and violence.

I know she is right because my former students have told me that my class helped them feel more deeply linked to others than before — a lesson in empathy to last a lifetime.

We lost so much to COVID: in-person learning, cultural experiences and field trips, and many elderly Holocaust survivors who passed during the pandemic.

Let’s not lose another precious year together. The city’s museums are ready to welcome students back, and I am eager to meet them.

Sally Frishberg (née Sara Engelberg) was born in Urzejowice, Poland in 1934 to a Jewish family. She escaped the Nazis’ resettlement orders by going into hiding with her family. She first settled in the United States in 1947. In 1958, she became a teacher at Fort Hamilton High School, where she taught until 1991 and was responsible for establishing one of the country’s first Holocaust courses. In 2005, Sally was bestowed the Yavner Award for Excellence in Holocaust Education by the State of New York. She served as a gallery educator for many years at the Museum of Jewish Heritage — A Living Memorial to the Holocaust and is now an active member of the Museum’s Speakers Bureau. She has two children and four grandchildren.