Admissions information recently posted on the website of a competitive, sought-after public middle school in Brooklyn seemed to have a tone of exasperation.

“We are awaiting further direction from the Department of Education regarding the admissions process for the 2022-2023 school year. As soon as the information is available we will share it with the community,” the message said, urging families to check “frequently” for updates.

“We’ve left last year’s information available below but we urge you to read the paragraph above because there is no info yet,” it continued.

For a second year in a row, parents, students, and school leaders are plunging into an admissions season clouded by COVID and filled with uncertainty.

Unlike many other parts of the nation, all public school students in New York City must apply to middle and high schools. The application process for high school can be ruthless, time-consuming, and a driver of segregation. Many middle schools similarly “screen” 10-year-olds based on past academic performance.

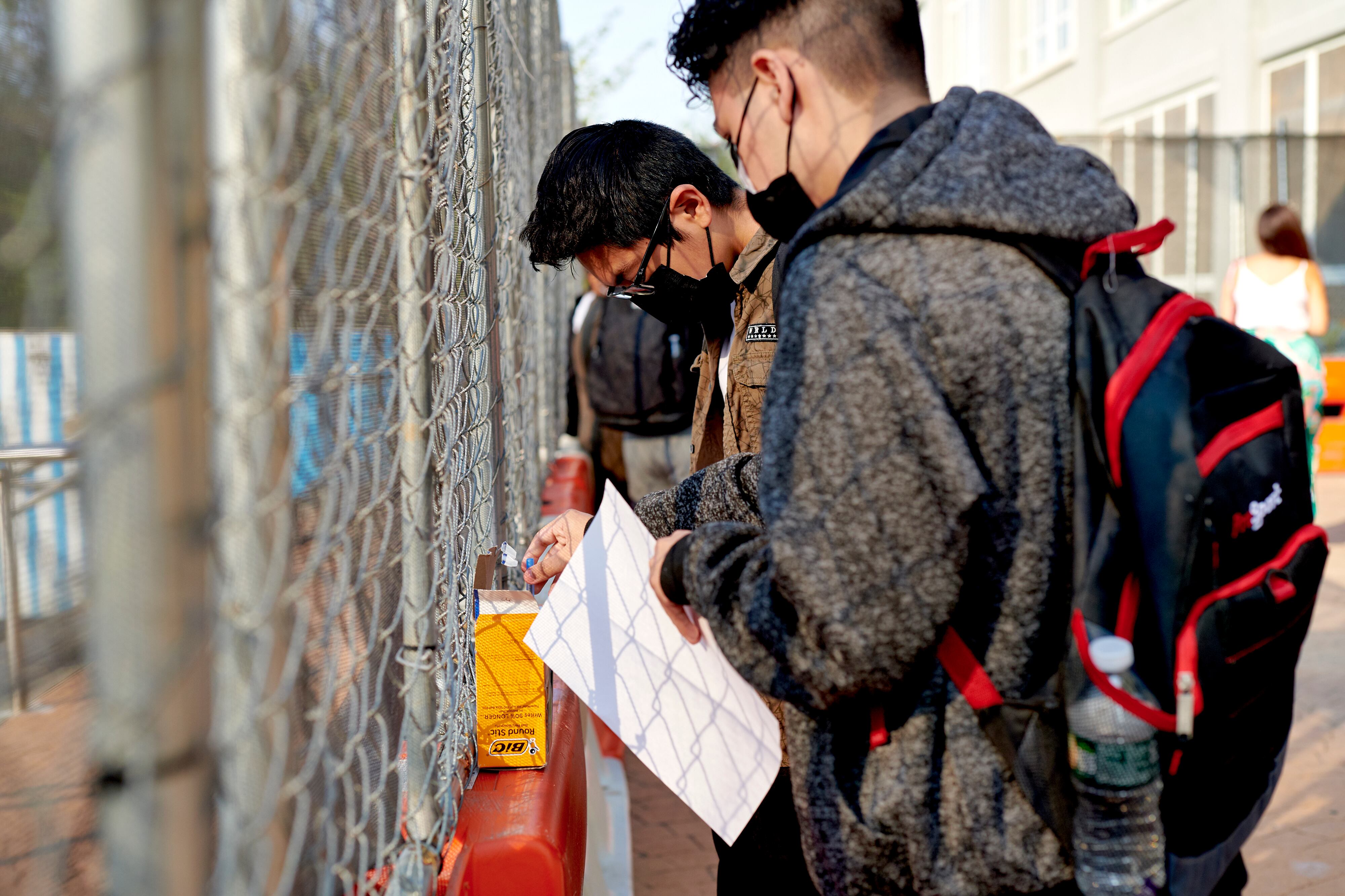

Typically at this point of the year, families would have already begun their sprint to find a good match, touring campuses and parsing admissions requirements. Instead, applications haven’t even opened yet, and tours have been limited, while school leaders and students alike are waiting to learn how — or whether — schools will be allowed to sort students.

“The only thing we know is that things are unstable,” said Yasmin Schwartz, assistant division director at the Cypress Hills Local Development Corporation, a social service agency that, among many other things, helps guide families through the application process.

One thing is clear: The pandemic will continue to force changes to the process. A new mayor, who will be elected on Nov. 2, could further upend things.

Here’s what we know — and don’t know — about applying to middle schools and high schools this year.

When will applications open?

Education department officials have not yet provided a specific timeline.

So far, families have been mailed welcome packets with information about how to log in to the MySchools platform, which allows them to research schools and ultimately rank up to 12 choices on their applications. (Applications can also be submitted by a guidance counselor, or at one of the education department’s Welcome Centers.)

Information sessions for high school are planned for early November, according to an email blast from the education department.

“We know families are eager for more information and we’re finalizing plans and will have more to share soon,” said education department spokesperson Katie O’Hanlon.

The delay may be an improvement over the typical applications timeline, said Laura Zingmond, senior editor at the school review site InsideSchools, which helps families understand the admissions process. She hopes it will stick beyond the pandemic years.

“High school admissions should never happen at the beginning of September,” Zingmond said. “No eighth-grader should start off eighth grade thinking about where they want to start high school, before investing their energy in doing their best in eighth grade.”

With no deadlines yet, and no information about screening criteria to share with prospective families, schools haven’t scheduled as many tours, or have even cancelled them, according to Elissa Stein, a consultant who helps families with the application process. Those that have happened fill up quickly. Few are offering opportunities to see schools in-person.

“The opportunities to research are stunted because I think schools aren’t announcing things until they know how things are going to work,” she said. “Everything came to a standstill. I feel so sorry for families.”

Will schools be allowed to screen?

New York City’s middle and high schools rely on selective admissions on a scale not seen anywhere else in the country.

Many advocates for more diverse schools say the screening process enables the most coveted schools to shut out certain students, especially those who are Black, Latino, have disabilities, are learning English as a new language, or come from low-income families.

Because of the pandemic, many of the admissions criteria commonly used — test scores, grades, and attendance records — were not available or were dramatically different from previous years. So last year, screening was eliminated in middle schools citywide. There weren’t even auditions for arts programs.

High schools were allowed to continue to screen, relying on test scores and grades from before COVID struck, when students were in sixth grade. Auditions went remote, with students submitting videos of themselves performing or photos of their work.

For this year’s admissions, there is still a dearth of information for schools to use to select students. Many students did not receive traditional grades, and most did not participate in state testing this year.

In virtual information sessions, some principals have hinted at how they’d like to use screens this year. But many school websites warn that they’re still waiting for the education department to approve their admissions criteria.

“We are always committed to a fair and equitable admissions process,” O’Hanlon said. “We are continuing to evaluate how the pandemic has impacted options for admissions and are looking forward to sharing this guidance with schools soon.”

No more admissions zones?

New York City’s high school admissions process was designed to give students access to schools beyond their ZIP codes. But in practice that is often limited by admissions priorities.

Last year, the city eliminated the use of district-level priorities in high schools, which had long helped some wealthier corners of the city carve out access to their own elite set of schools. This year, there is confusion over whether high schools can maintain admissions priorities based on zones where students live.

The education department website says that all geographic priorities have been lifted. But parents and school leaders seem to be caught by surprise. For example, the Fort Hamilton High School in Brooklyn still lists information about how to apply to its zoned program, and the city’s MySchools page also lists the school as having an admissions zone.

“We’re working to update external information to ensure accuracy,” O’Hanlon said.

Zones can be a barrier to schools reflecting the diverse demographics of the system, even in neighborhoods that are diverse. A task force appointed by Mayor Bill de Blasio that focused on ways to better integrate schools recommended in 2019 eliminating all geographic admissions priorities.

But changing attendance zones is a contentious issue tied up in race and economic status, with families often fighting to preserve their access to schools nearby. Alysa O’Shea, a representative for Queens on the education department’s Citywide Council on High Schools, said at a recent meeting that parents in her borough find the removal of geographic zones “unreasonable.”

“Here in Queens, we’re one of the most overcrowded boroughs, as far as capacity of schools, and we also face some of the longest commute times, even within the borough,” she said. “How can you just expect a borough … to just give up all their seats to anybody who wants to come here?”

Ending geographic priorities would open more opportunities for students in neighborhoods like Cypress Hills, a small, largely low-income and immigrant Brooklyn enclave on the Queens border, said Sindy Nuesi, director of the Middle School Student Success Center at Brooklyn’s Abraham Lincoln campus run by Cypress Hills LDC.

After the city ended district priorities last year, 91% of the students that Cypress Hills LDC works with were accepted to one of their top three school choices — an increase of 10%. Though a stone’s throw away from Queens, Nuesi said she used to have to steer students away from schools where geographic priorities made it impossible to get in.

“Now I’m being more open with students when they mention these schools that previously had these restrictions. That’s just me having hope” that the removal of geographic priorities will stick, she said.

What about the SHSAT?

Some of the city’s most competitive and coveted high schools are specialized schools, like Stuyvesant and Bronx Science, that admit students solely based on the Specialized High Schools Admissions Test, or SHSAT.

This year, students who register for the test will take it in their middle school, as they did last year. Students must sign up by Nov. 15 and the test will be administered on Dec. 2.

Previously, students who signed up for the test had to take it on a weekend at certain designated locations. (That will continue to be the case this year for students in charter schools, private schools, and those who are homeschooled.)

The controversial test is required by state law, and many blame it for the stark underrepresentation of Black and Latino students. They make up only about 10% of enrollment in specialized high schools, but almost 70% of students citywide.

Specialized high schools — widely regarded as the Ivy League of public school options — also enroll fewer students from low-income families, students with disabilities, or those who are learning English as a new language, compared to the citywide averages.

Since at least 2016, middle schools that historically sent few students to specialized schools have offered the test during the school day on campus, in efforts to boost the numbers of admitted Black and Latino students.

Last year, while middle schools were closed because of a spike in coronavirus cases in the city, students had to go to their school to take it, in an effort to increase social distancing.