“Having classes in person will be better—I’ll have a teacher in there.”

“I’ve been taking care of my sister because my parents have been working. I’m going to miss that.”

“I don’t want to go back to school. I’m going to miss not having to look presentable.”

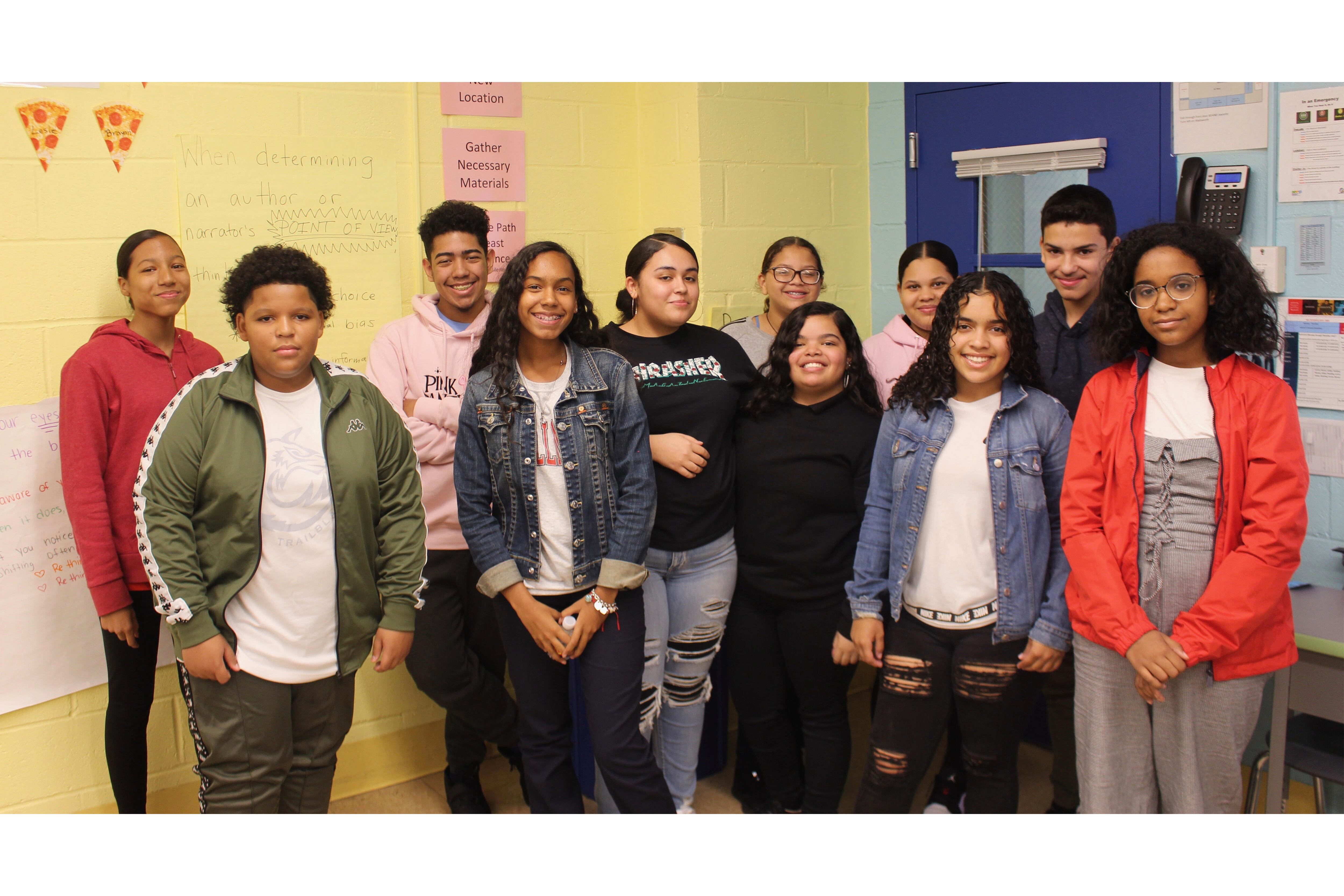

The dozen students Zooming together in May, from various high schools across the city and in Florida and New Jersey, had attended middle school together. They were all members of the inaugural graduating class of School in the Square, a small, progressive charter middle school in Washington Heights known as S2, and they’ve become experienced oral historians as part of a five-year project to document the voices of their fellow alums.

From their Zoom discussion last spring, they created a list of questions to interview other students about both their anxieties and excitement about heading back to school this fall. In their first two years working on the project, they have collected stories about the pandemic, the racial reckoning following the murder of George Floyd, the struggles with remote learning and adjustment to high school.

The S2 Intergenerational Participatory Research Collective, as the project is called, was formed in May 2019, just as these students graduated from their 300-student charter middle school located in the shadow of the George Washington Bridge, serving mainly Dominican American immigrants or children of immigrants from Washington Heights, Inwood, the Bronx and Harlem. The project provides a more meaningful way for the school to understand how their graduates are faring and how to help, if needed.

“We wanted to keep track of our graduates and get a sense of how they are doing in their high schools,” explained the school’s founder Evan Meyers, a finance professional turned history teacher. “What can we learn from them on how to support our students better? Which high schools serve our students well?”

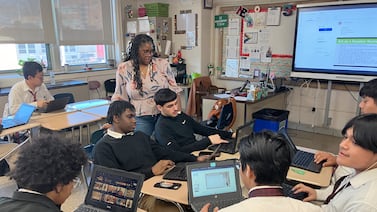

But rather than crunching data or waiting to see who graduated high school in four years, the school hired two CUNY professors, Michelle Fine of the CUNY Graduate Center and Samuel Finesurrey of Guttman Community College, with experience with Critical Participatory Action Research to train the students in both oral history and qualitative research skills.

Added to the mix was Arnaldo Rodriquez, the school’s eighth grade and alumni counselor, whose role is to help their graduates now in high school deal with any issues that arise and are revealed by the interviews. His role is as the “transition counselor,” to check on and provide support for the school’s approximately 500 graduates and their families, wherever they are. Or as he put it, to “provide a home base close to home.”

Critical Participatory Action Research, or CPAR or PAR as it is sometimes called, has a long history not just in the U.S. but in El Salvador, South Africa and New Zealand, among other countries. It is based on the idea that “the ones who have been impacted have a right to shape and implement the research and what consequences come out,” explained Fine, a professor of critical psychology, women’s studies, American studies and urban education at the CUNY Graduate Center.

For over two years, the students, now 15 and 16, and high school juniors, have been interviewing each other and their peers from the school’s first graduating class to understand what they’ve confronted, as they moved beyond their small middle school to 37 different high schools.

What was it like to move from a small, intimate school to a big one? What is their experience going from a neighborhood school that is predominantly Latino to a different high school in New York City’s highly segregated system? What’s it like to go into more challenging classes? Or into schools where they are met with metal detectors? These are some of the questions that they asked their friends and former fellow students.

“There were no scripts or teachers telling us what to say and do,” said Naomi Pabon, 16. “We took the time to interview our friends in order to get raw material, something that is true and honest.”

Learning how to do oral history

Meyers, who worked in finance for two decades before graduating from Columbia’s Teachers College, launched the middle school in 2016 based on a “culture of care,” he said. The goal is for students to be well known by the staff, with small classes, advisories, electives and class trips and connections to local community organizations.

The school’s board of directors is filled with finance professionals and bankers who raise over $2 million a year to help fund the school in addition to what it receives from the city. A small portion of that money supports the oral history project, which pays a modest stipend to the student oral historians.

None of the 12 graduates had any experience interviewing others before, and Finesurrey, an experienced oral historian, helped them learn oral history skills. He brought three of his Guttman students who had learned oral history in his class to help teach them interviewing skills.

In small groups, they generated questions. Where do immigrant students feel at home? What are the joys and burdens of living bilingually? How did they develop personally while a student at S2? What’s the transition to high school been like? What experiences have they had in terms of safety, fear, surveillance and policing in high school? They tried them out on each other and learned to record conversations.

Watching them on Zoom, Finesurrey takes notes, but the students are the ones designing the questions and reworking and revising them.

“You don’t just want to ask: ‘Do you feel safe in your school — yes or no?’” said Naomi. “Each subject we broke into different questions like ‘How do you feel about using the bathroom in your school? ‘Is there an area in the school where you don’t feel safe — where and why?’ ‘Do you feel safe with police in the school or metal detectors?’ ‘Is there a teacher you can talk to when you need to — like Mr. Rodriguez?’”

It was hard at first.

“It was a mess,” said Brandon Mendoza, 15, who began by interviewing his best friend. “Then we got into laughing because we were both nervous. But eventually it got easier.”

Naomi interviewed 10 people, as did the others. She said the students she interviewed described very different experiences at their new high schools.

“My school was trying to get the students college-ready,” she said. “Other kids talked about their schools where the discipline was so strict.”

Altogether, the 12 researchers conducted interviews with 36 of their former classmates the first year and 60 the second. When the pandemic hit, schools closed and moved to remote learning, and the researchers interviewed on Zoom. The pandemic and struggles with remote learning became a subject.

The alumni were dealing with the pandemic as well. In addition to his own schoolwork, Brandon had to help his sister with hers because both their parents were working — his dad in a supermarket and his mom taking care of elders. Then both his mother and Brandon got sick with COVID. He was sick for two weeks and his mother, a home health aide, for a month. They both survived, “but we thought she was going to die,” he said.

The middle school has been trying to help families of its alums along with current families stay afloat during the pandemic. The board’s fundraising efforts have helped to pay for diapers, school supplies, baby food and other pressing needs. With help from the West Side Campaign Against Hunger, they hold a food bank every two weeks, open to all S2 families and families of alums, with whatever is left distributed to locals. They have done home deliveries, had a coat drive, and a full summer program.

Many of the students interviewed struggled with mental health issues because of the pandemic itself, the isolation of working remotely or being cooped up in small apartments in multigenerational households. After George Floyd and Breonna Taylor were killed by police, police violence, racial justice, and activism became interview topics.

By that time, they had not only developed their abilities to ask questions but also to engage in discussions about race and racial justice. Both collective members and their interviewees credited their eighth grade social studies teacher, Maeve Pfeiffer, with helping them think about and talk about race and social justice.

A number of the interviewees talked about the work they did in Pfeifer’s class critiquing a range of standard textbooks and whether they were critically conscious, historically accurate, boring or interesting. For their final assignment, students collaborated to create their own history textbooks about a particular era in history.

Sharing their work

Last fall, the students were invited to present by Zoom about the impact of COVID on young people in the schools to Deputy Mayor J. Phillip Thompson and state education officials.

Six of them presented on mental health Issues that arose because of the pandemic, the effects of online learning and the rise in racial consciousness and youth activism — all drawn from the collective’s oral histories.

Ashley Cruz started off by sharing her own experience before she presented excerpts from some of the oral histories that dealt with mental health.

“Beyond school, how I adapted to the virus, I was able to focus on myself and reflect on my own feelings for the first time. I encouraged other young people I spoke to to find a trustworthy individual who they can talk to,” she said.

She also shared excerpts from several oral histories:

“I was going through a dark time and I didn’t know how to deal with my emotions. I was unhappy and anxious. I didn’t know how to speak on my mental health. I tried to focus on school while at the same time accepting the fact that what we know as ‘normal’ fell apart completely,” said one.

Alondra Contreras and Aidan Lam presented quotes from the students’ interviews about their responses to the murders of Floyd and Taylor and the protests that followed.

“My mother took me to a protest in New York. When you hear people speak about past experiences, it’s very awakening. I feel this whole movement has shown how prevalent racism is in our country,” said one.

Other students talked about the experience of talking to their families who didn’t share their feelings of outrage:

“The people in our country originated from Africa. [I say to my family]: support something, say something,” said another. “My family doesn’t consider themselves people of color. ‘I’m Dominican’ They’re like, ‘I’m Spanish.’”

The research project continues this fall with the 11th graders interviewing the charter school’s sixth graders as well as reinterviewing their peers as they are starting to think about college.

They will also be teaching S2’s sixth graders how to interview their peers about what concerns them and in doing so, they’ll be passing on a torch.

“They have become masters of the process,” said Finesurrey. “They have put their imprint on something they are really expert on — their own generation’s experience in this horrific time.”