When Ryan Horodecki walks into Voyages Preparatory, a transfer high school for students who have fallen behind and are at risk of dropping out, one of the first things he sees is his self portrait.

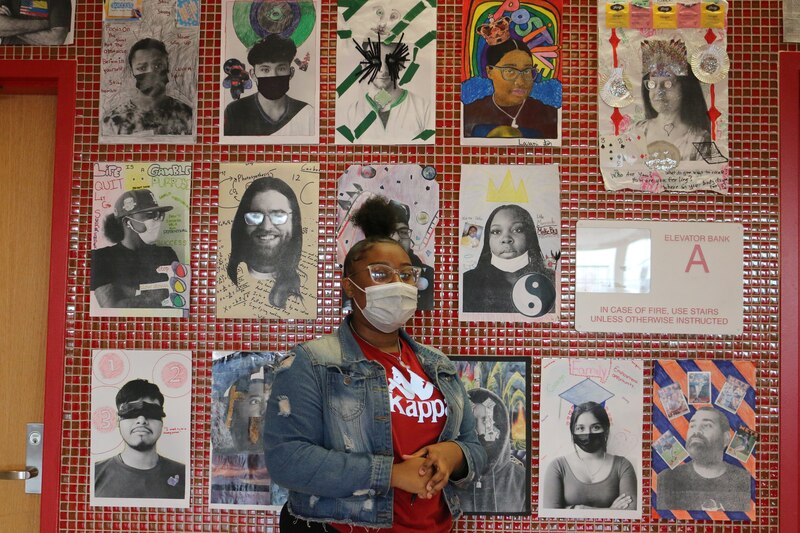

The lobby of the Elmhurst, Queens, building, a former factory with floor-to-ceiling windows, is lined with portraits students made in the first weeks of school. Horodecki’s hangs within eyeshot of the entrance.

It shows his face split down the middle, with one half wearing a surgical mask, the other uncovered. In the background is the Brooklyn Bridge, representing his home borough.

“I had first-day of school nerves,” he said of the masked photo he used to create his self-portrait. “And then I was a little bit more open, and I decided to take my mask off. And that’s kind of what I wanted to represent inside my photo.”

After a grueling and often heartbreaking year, when about half of the school’s 250 students learned remotely full time, Voyages Prep faced enormous questions about how to come back together.

“We need to get to know each other all over again, and in a different way.”

It’s a challenge faced by many schools in New York City, where education leaders have promised to make student mental health a priority. The city hired hundreds of new social workers and is using new screening tools to check-in on how students are faring socially. But the transition back has been rocky, with educators reporting more fights on campus, and the city ramping up the use of metal detectors after five guns were uncovered in schools over a recent two-day span.

School leaders at Voyages searched for their own way to process what they’d been through, to forge personal connections, and to get ready to teach and learn.

The answer they settled on was art.

“We need to get to know each other all over again, and in a different way,” said Katherine Martinez, the school’s assistant principal.

With the help of artist Traci Molloy, students spent the first two weeks of school immersed in creating a self-portrait, a collaborative class poem, and building a schoolwide sculpture made of meaningful objects brought in by the community. Working together connected the students to each other and their teachers, and then as the completed projects were displayed in the lobby, it gave the students a greater sense of being part of the community, school leaders said.

“Walking into the lobby and seeing your artwork and your portrait, that’s powerful. You belong here,” Martinez said.

Since Voyages is a transfer school, students graduate throughout the year as they accumulate credits, with students coming and going all the time. As a result, Voyages is always conscious about establishing its culture — the aspects of the school that make students feel connected and inspire them to show up for class.

They’re also constantly catching students up who have fallen off their educational track. To enroll, students must be under-credited after at least one year at a traditional high school. Perhaps that’s why the leaders at Voyages weren’t too concerned with filling learning gaps in the return to in-person learning.

“The loss was being in community with each other,” Martinez said. “That’s what school is about. That’s the learning loss.”

For Bryanna Lopez, an 18-year-old hoping to graduate this year, working on the self-portraits helped her bond with her classmates as they discussed their pieces and what they represented.

“It was like we were socially getting ready,” Lopez said. “Other schools, like my sister’s school, they made her jump straight into that. Nobody’s socially ready for that, to be with a bunch of people, after being stuck inside of four walls.”

Her portrait looks like shattered glass, with her face distorted by jagged edges cut apart and stuck back together again. It’s a representation, Lopez said, of how she didn’t feel like herself after the March 2020 lockdown, and has now become a new person.

After school moved online, she lacked the motivation to log into classes, missing the social connections she got from being in a classroom. Lopez said she spent endless hours watching Netflix alone.

What students need most right now, Lopez said: “each other.”

When New York City became the epicenter of the pandemic, so much of that sickness and loss was concentrated in the Queens neighborhoods surrounding Voyages Prep in Elmhurst. It seems like no one in the school community was left untouched.

“You don’t ask, ‘Did coronavirus affect your life?’ No. It’s like, ‘Everybody in my family got sick. Everybody I know got sick,’” said Nicholas Merchant-Bleiberg, the school’s principal.

Even before the pandemic, the need to earn a paycheck pulled many away from their classes. The economic devastation brought by COVID only made it more necessary for students to work. They logged into classes while working shifts at fast food restaurants and coffee shops. Others fled to hunker down in their native countries, like Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, and Uzbekistan.

To build community again, the school’s leaders turned to Molloy. She had worked with the school previously and has experience guiding young people through trauma using art, including refugees in Portland, Maine, and children who lost a parent in 9/11.

At Voyages, Molly got to work by first training teachers. The school was able to tap a newly flush budget buoyed by additional federal, state, and city dollars, to pay staff who opted to come in during the summer. They spent weeks completing the projects themselves before leading students in the same assignments.

“Adults need transition, too. And adults need time to process this,” Martinez said.

When the school year kicked off, the project got integrated into what’s known as “the course,” a required class that every student takes for credit. Driven by current events and student interests, every trimester focuses on a new topic, with heavy emphasis this year and last on COVID and social justice issues. On a recent afternoon, a group of students in the course interviewed Merchant-Bleiberg about critical race theory and whether he had ever faced racism.

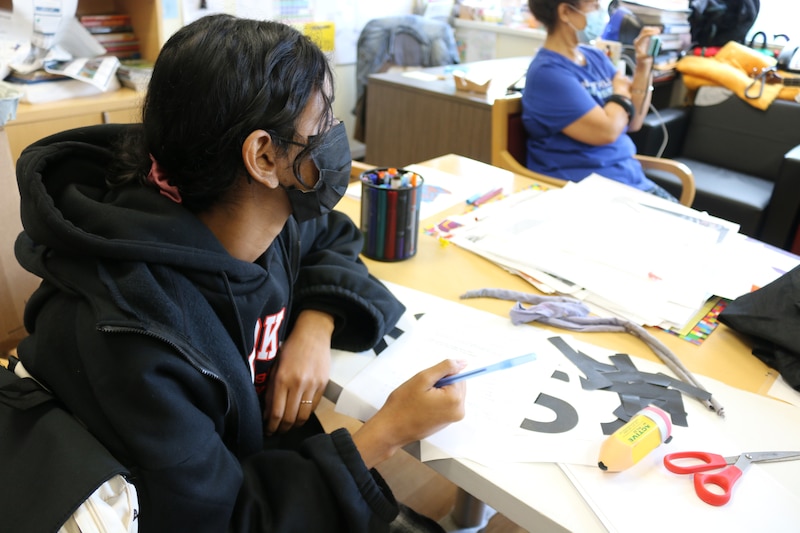

But before diving into that, the students spent two weeks in the course on a series of art projects. To build a sculpture together, they brought in or created objects that were important to them. In explaining the value of each item, students and teachers learned about each other — their immigration journeys, their family systems, and the challenges they faced to get to school every morning.

“The trust and the safe space that was established and for people to be vulnerable and just go for it,” Molloy said. “It was awesome.”

As a transfer school, Molloy said there were some built-in advantages for completing such a project at Voyages. Class sizes are small, and a partnership with Queens Community House, a social services organization, meant that there were counselors on-hand in every classroom.

Students also worked on a poem together, passing around a piece of paper and adding a line. And they had a headshot taken for their self-portraits, and were given three prompts to explore: Their experience with COVID, their goals for the year, or to explain their personalities. Many decided to combine all them, and explained what they intended to show through an artist’s statement.

The goal was to give students multiple ways to participate. They were graded on whether the work was completed.

“Really what we’re trying to do is give people the opportunity to transition back to school and share in safe ways. One of the things I’m really keen on is to give people options,” Molloy said. “Especially in a school where there are power dynamics, you can’t say, ‘Ok now you have to write about this.’”

Lailani Greaves, an 18-year-old who started at Voyages this year, filled her self-portrait with bright colors and the word “positive” written in bubble letters. Her artwork is vibrant even though she said living through a pandemic has been a “shaky” experience. She lost someone who she considered a grandmother.

But Greaves also got a new job, as a door-to-door salesperson, that she said taught her responsibility, gave her a test of independence, and brought her out of her shell. Through the art projects, she worked on her “communication and collaboration” skills that Greaves said she can apply to her new job.

After two years of not taking high school seriously, she started at Voyages this year and is eager to get back on track. In her portrait, Greaves is wearing a “crown of positivity.” The arc of a rainbow frames her face.

“There’s a rainbow, always, after the storm,” she said.