As a middle school science teacher who has long advocated to transform our public school rooftops and waterfronts into climate-resilient learning spaces, I would never have imagined receiving Mayor Bill de Blasio’s outdoor learning plan with such bitterness.

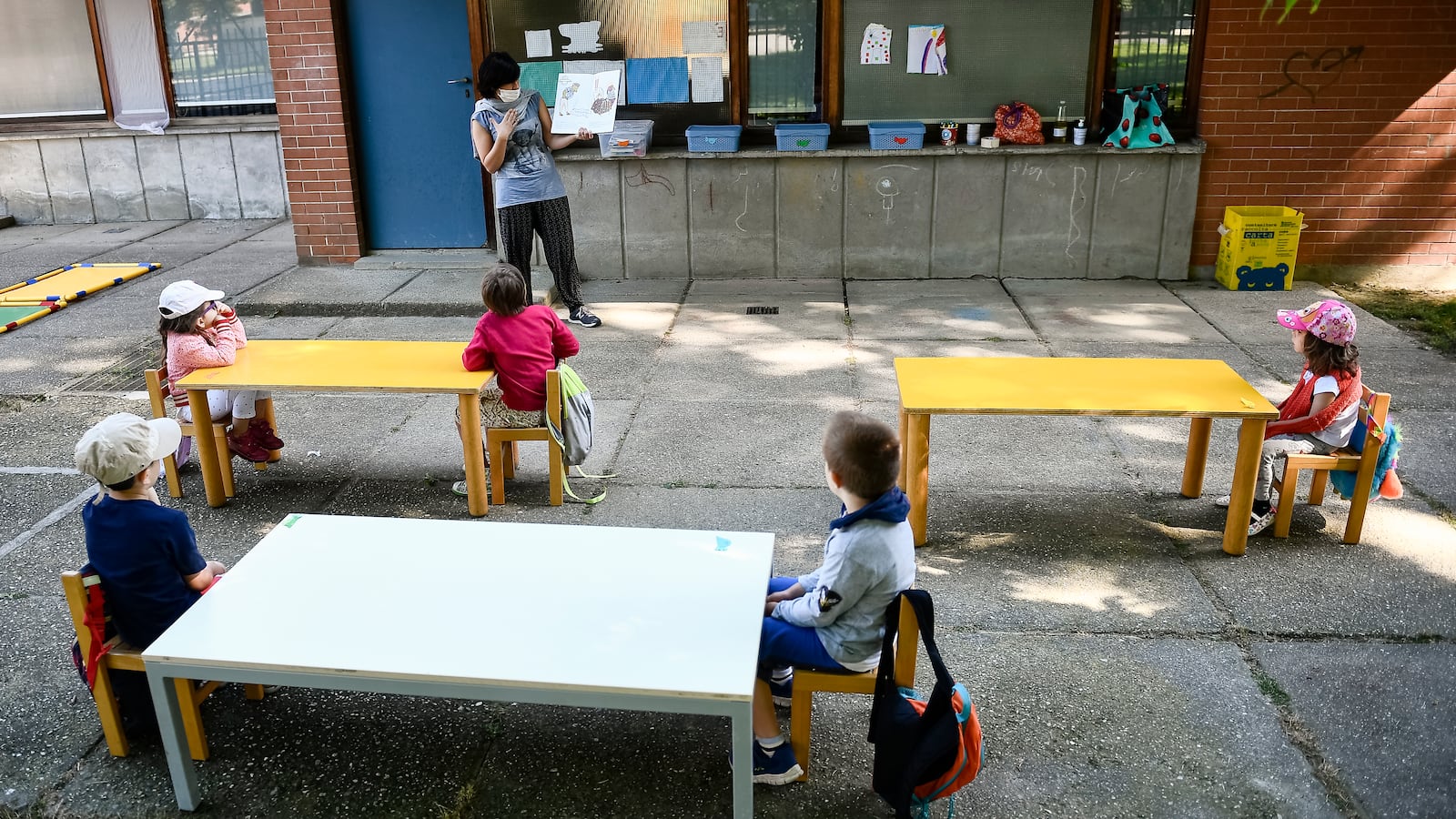

Since coronavirus is less likely to spread outdoors, letting all New York City schools hold class in public parks and on cordoned-off city streets, on its face, seems like a positive development. But I didn’t need to read the fine print to know that our immigrant, Black, and brown communities — the ones that have been hit hardest by the COVID-19 crisis — would get the short end of the stick. I didn’t need to know who organized and petitioned for outdoor learning to know that the “nice white parents,” a perennial force for maintaining inequities in one of the nation’s most segregated school systems, would get their way. Again.

When the outdoor learning plan was first announced, my instinct was to blame myself. Seven years ago, my students and I won the grand prize for a national STEM competition that awarded my school over $110,000 in technology from a mega tech corporation. We competed for the technology as a tool to advocate for a green roof and to facilitate a culture of community advocacy in the classroom.

We used our brand new laptops to research the proposal we’d have to write to the School Construction Authority — complete with renderings, cost projections, and fundraising plans. We learned that we would need to apply for grants from the City Council, from our borough president, and from the Department of Environmental Protection or continue to seek the charity of corporations and wealthy donors. We also learned that the PTAs of some of the majority-white public schools just blocks away from our own school worked around the construction authority constraints by raising nearly $2 million. We learned that we’d have to get elevator access to the roof in order for our proposal to even be considered. Needless to say, we decided not to move forward.

Fast forward seven years, and the city is now permitting — and promoting — outdoor learning amid the coronavirus pandemic, and urging PTAs to help cover costs associated with it, like barriers to close streets to cars and portable bathrooms. I was aghast. Why, I wondered, is the city asking schools to use private funds to meet basic safety needs. Sure, schools Chancellor Richard Carranza suggested wealthier PTAs consider helping out schools with greater needs. But with no mandate and no plan for distributing dollars, the plan will inevitably benefit schools with the funding to pull it off.

Given NYC’s long legacy of segregationist policies, from redlining to school screens, it is no surprise that New York’s most marginalized schools are far less likely to have access to green spaces, and are far more likely to be in close proximity to transfer stations and major expressways, exposing school communities like mine to harmful outdoor air pollution.

Over the past 11 years teaching at a Title I school, I have seen Hurricane Sandy’s devastating storm surge displace my students and their families. I have seen the development and gentrification of the Gowanus waterfront spew more raw sewage into the public waterway my students and I have sought for so long to clean. I have seen deadly heat waves increase in frequency and intensity, and the closure of one of the few public swimming pools my students used — built, knowingly, over toxic waste. I have seen families separated due to inhumane federal immigration policies, and children living in fear of ICE raids. And most recently, I have seen my students and their families lose their loved ones to COVID-19, and I have seen them lose jobs and homes to the pandemic’s economic fallout.

Despite all of it, my students are eager to make use of their science and advocacy skills to improve the environment, to better the chances of surviving COVID-19 and the climate crisis, both of which disproportionately impact the neighborhoods where they live.

For classroom teachers, the expectation has long been to use our personal and crowdsourced funds to gather the most basic resources for our classrooms. Two months before the world even knew about COVID-19, I wrote a $238 Donors Choose Grant, “Cleaning Supplies for a Bright and Healthy Classroom!” Given the prevalence of COVID-19 among my school staff, and in the neighborhoods where my students live, it’s possible the grant saved lives.

As I stare at a screen for hours on end, attempting to plan hybrid lessons, while hoping to find ways to engage my students in the fast approaching Global Day of Climate Action, I’m reminded of how demoralizing and disheartening teaching, especially teaching our most underserved communities, can be. Over the past year, I’ve felt so far removed, and even barred, from the joy of empowering my students to take climate action, to fight for health justice, and to make science a tool for bettering lives. This fall, for the first time in my teaching career, I’m not feeling the normal insuppressible excitement and hope that a new school year brings.

As far as I’m concerned, the educators and families most directly impacted by this public health crisis and by the ongoing climate crisis have been most excluded from life-sustaining information. I, for one, drank water out of my classroom sink for more than three years before learning that it was leaching unsafe levels of lead.

For too many of us, the promises being made in the name of equity are just reminders of demands long ignored and resources long withheld. The outdoor learning plan is yet another attempt to advertise equity while privileging the most affluent schools. The outdoor plan is really for the nice white parents.

Lynn Shon is a public school teacher in Brooklyn. She’s on Twitter @lynnshon.