None of the bureaucratic chaos of New York City’s school reopening plans was on the mind of 9-year-old Juliette Ramirez, a fourth grade student returning on Tuesday for the first time in six months to the Castle Bridge School in Washington Heights.

Some of her worries were typical, such as the butterflies of meeting new classmates, but other concerns were new. As she looked across the playground where students and parents gathered, she couldn’t recognize anyone because of their masks.

“What makes me nervous is catching the COVID — and being the only girl in my class,” said Ramirez, wearing a bright red mask with white polka dots as she waited to enter the elementary school serving 185 students. “I’m excited that I get to be back.”

Mayor Bill de Blasio has remained steadfast that the nation’s largest school district open its doors because remote learning has been difficult for many families across the city. Yet, many educators remain wary of being back, worried about students — and their colleagues — keeping masks on. And even with the reopening of buildings, under the city’s hybrid model most students who are returning to classrooms will still only be on campus one to three days a week.

The mayor’s plans have run up against many roadblocks, including immense staffing gaps that are untenable for many principals, and concerns over ventilation, which continue to worry some teachers. The mayor delayed reopening twice, and the number of students opting to stay out of school buildings steadily increased over the past few weeks to 48% of the district’s roughly 1 million students. The union representing the city’s principals said they lacked faith in the mayor’s ability to steer reopening plans, calling on him to cede control to the state.

De Blasio’s reopening plans could also hit another major wrench: The mayor has pledged to shut down the school system if 3% or more of coronavirus tests come back positive over a 7-day average. For the first time in weeks, the daily positivity rate jumped past 3%, according to health department data from Sunday, the most recent available.

The climbing rate has the city on edge. Though cases trended downward this summer, New Yorkers are still reeling from being at the epicenter of the virus, which has killed 24,000 city residents, and some public health experts have warned that another wave could hit as the weather gets colder and more people congregate indoors.

Health officials are keeping their eye on a troubling rise of coronavirus cases in some Brooklyn neighborhoods, and have stepped up enforcement of virus restrictions and efforts to educate the public about issues like testing and mask-wearing in those areas.

“The geography is very specific,” the mayor said of the outbreaks, which have been concentrated in some Orthodox Jewish communities. “There is not a lot of interconnection with public schools in these areas.”

De Blasio said there is no evidence that spikes are happening within schools and that the city would not close campuses in individual neighborhoods seeing upticks. Additional testing sites have been set up in and around public schools in those areas, he said.

After classes let out on Tuesday, the United Federation of Teachers called on the mayor to reconsider his approach and shut down about 80 schools in hot-spot areas if the virus is not quickly contained. Though they did not outline a specific threshold that should force a closure, their alarm is notable: labor officials’ demands have held sway in driving previous big decisions, such as delaying in-person instruction, throughout the city’s long reopening saga.

“The city can’t sit by and let the virus spread in these or other zip codes for days until it drives the overall city rate above the seven-day threshold,” United Federation of Teachers President Michael Mulgrew said in a statement.

Next week, the city will begin regular, random testing of students and teachers to monitor for the virus. Every month, a certain percentage of the school community will be tested, depending on the school size.

The mayor also called on families and educators to be understanding while schools implement an entirely new approach to teaching.

“All of this is incredibly difficult and complex. Everyone is doing their best,” de Blasio said. “Let’s be honest: The first days will take some adjustment.”

‘Am I making the right decision?’

It’s been one week since Stuart Pennant dropped off his 4-year-old son at Castle Bridge to start pre-K, but he’s still anxious, and said he would pull his son out of school if the city’s rate hits 2% over several days.

“Am I making the right decision? I’ll let you know in a year,” said Pennant, who can afford child care and could have kept his son home full-time, but felt it was important for his son to interact with other children after losing the spring.

It helps, he said, that his son is one of just five students in his class.

As children streamed into the playground around 8:30 a.m. on Tuesday, they were directed to their class groups, named after trees like Mulberry, Oak, and Aspen. Just 36 students showed up to Castle Bridge on Tuesday, even though 48 students were slated to come in person to the dual language school, where about two-thirds of students come from low-income families.

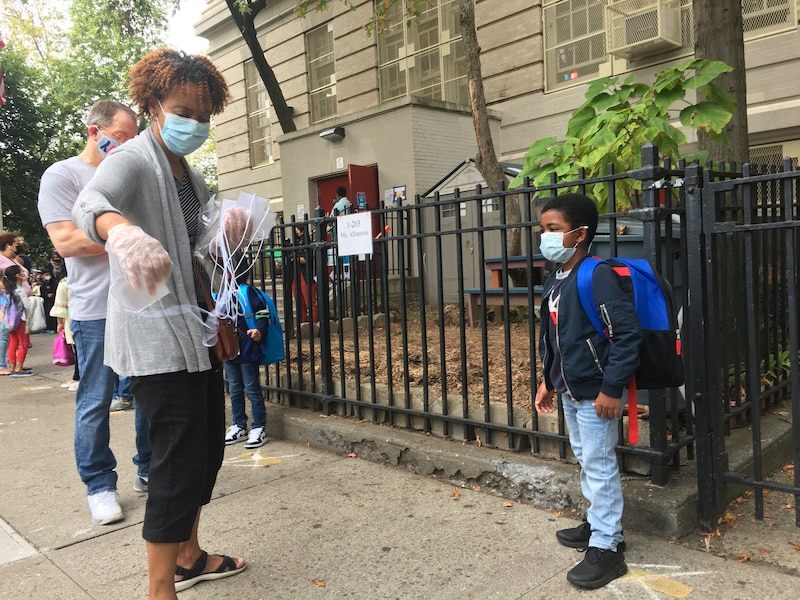

Julie Zuckerman, the principal, said they’re trying to figure out why the others did not show. She greeted students by name and goofed around with a few who had lined up against a fence next to her. One teacher asked a few students how their summers were, moving his thumb up, to the side, and down — they said it was good. Another teacher bumped elbows with a student who had just walked up to her group.

Juliette, the fourth grader, said she could feel the difference from past years.

“It’s weird because it’s been long — not too long, but long,” Juliette said. “We only have been on screens this whole time, but now we get to be in person.”

Juliette and her mom, who primarily speaks Spanish and needed to leave for work shortly after drop-off, approached the Aspen group, led by teacher David Rosas. Though he is a 21-year veteran teacher, it will be his first year at Castle Bridge. Zuckerman recently hired him to help with remote programming, but she shifted him to this mixed fourth and fifth grade class when the previous teacher took family leave.

“Honestly, I’m a little nervous, but I’m good because of these kids,” Rosas said.

He took Juliette’s temperature – 97.1 degrees. Her mother had not completed a mandatory health screen online, which asks several questions about how the student is feeling, so he gave her a paper copy to fill out.

Around 8:50 a.m, Zuckerman and a teacher shouted to the group that it was time to go in. A teacher translated in Spanish.

“Let’s do this. Time for a weird year!” Zuckerman said to the group as they arranged into single file lines.

‘I just need him out the door’

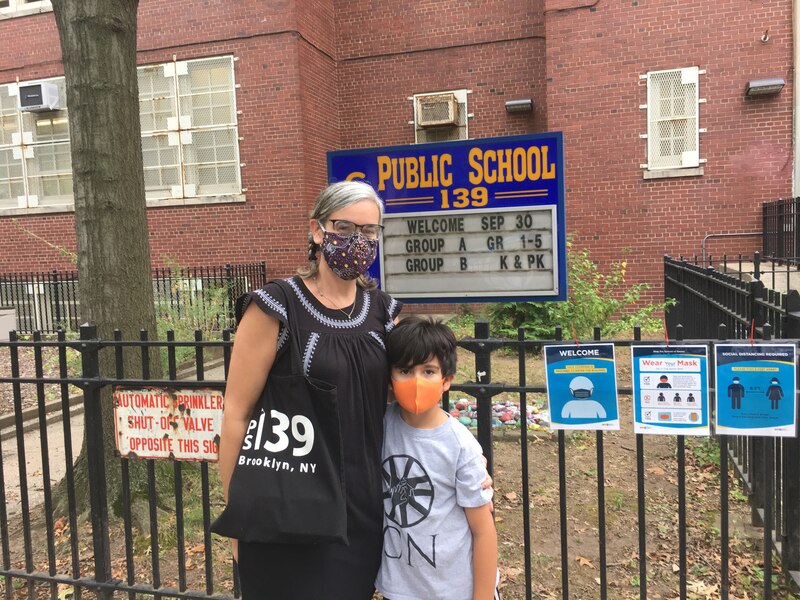

On a typical first day of school, the scene outside P.S. 139 in Brooklyn feels like a party, with balloons, welcome banners, and the local Flatbush Food Co-Op handing out apples to more than 800 students.

The mood outside P.S. 139 on Tuesday was more subdued.

As parents dropped off their children for a break from at-home learning, anxious students lined up for temperature checks, and teachers greeted students with smiles, asking, “Do you remember me from the video?” Fewer than 200 students were expected on the first day of in-person classes. At least one family showed up on the wrong day, a mistake many parents might fear as they juggle schedules for different children with in-person days varying week to week.

Ahmadou Bah was eager to send his three children back to school because remote learning has been challenging. But the immigrant from Guinea was turned away since his children were not scheduled for in-person learning until Wednesday.

“They just come to this country, they don’t speak English,” he said. “It’s not easy for them to understand from the tablet.”

Students at P.S. 139 have been split into three cohorts, which means they will attend school in-person for five out of every 15 school days, and learn remotely the rest of the time as part of the city’s “hybrid” model.

Parent Andrea Thomas said she is nervous about the risks of reopening schools, but could not allow her first grade son, Laquelle, to be stuck inside any longer without being able to interact with his teachers and peers in person.

“I just need him out the door,” said Thomas, a counselor at an organization that serves people with developmental disabilities. “I’m just going to see how it works.”

Even though Laquelle has been able to engage with virtual learning, Thomas often doesn’t have time to take him to the park and worries about the amount of time he spends on a screen. As Laquelle took his spot in line, standing on a purple and yellow chalked “X” on the ground, he was quick to remind others to stay 6 feet away.

The process of reopening P.S. 139 for in-person learning has been fraught. The school was briefly forced to shut down 14 days ago, before students arrived, because two staff members tested positive for the coronavirus. Fearing that safety protocols were not followed and that the building was not safe, the staff refused to go inside and instead worked from an outdoor courtyard.

Multiple P.S. 139 parents said they were confident that the school’s administration would follow health protocols and were impressed with the school’s communication so far. Some parents, like Raina Clark-Gaun, felt ambivalent about sending their children back into buildings, knowing that some teachers didn’t feel safe.

But both Clark-Gaun and her husband, who is a public school teacher for students with complex special needs, work full time and have struggled to simultaneously supervise remote learning.

“I couldn’t start my work until 12, so it was confronting either to have to quit my job or figure out a different solution,” Clark-Gaun said. “I am not, unfortunately, prepared to be the statistic of women in this country taking on all the reproductive work and not being able to have a career.”

De Blasio has emphasized that opening schools for in-person learning will help working parents. Paradoxically, the push to open schools created a staffing crisis for many schools, including P.S. 139, so acute that they cannot provide any live instruction on the days students aren’t in the school building.

Jessica Dowshen, a parent of a third grader, who waited for her son to return this week for his first day back in the building on Thursday, said his experience on Tuesday learning remotely was subpar.

When all students were remote last week, her son had at least three live streamed classes with a teacher each day. But now that teachers must also staff in-person learning, her son was given a few generic assignments that he finished in 30 minutes.

“They had all summer to be able to address these concerns, and they’re only really thinking about them in a tangible way when school doors are reopening” Dowshen said.

For those families whose children attended in person on Tuesday, she warned: “They don’t know what’s coming to them tomorrow.”

Christina Veiga contributed to this report.