New York City will begin training teachers on trauma-informed practices ahead of the start of school, officials announced Wednesday. But with just two weeks before buildings are set to reopen, educators remain worried there isn’t enough time to roll out the training properly.

The announcement came with new curriculum that promises to confront the trauma that students may have experienced with the loss of loved ones, of social connections, of family income and of routines as well as with the nation’s massive movement for racial justice.

Called the “Bridge To School” plan, it offers lessons on how to process grief and build coping skills after the tumultuous six months of coronavirus’s grip on the city, Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza said.

“The ability to not only be able to talk about that and be able to work through those emotions and have principals and teachers that are trained in being able to facilitate those conversations is just critically important for students,” Carranza told reporters.

Besides the lessons, schools will also incorporate social-emotional-focused activities and “community-building exercises” for the first few weeks of school that can be used for in-person and remote learning.

The city’s roughly 1,600 principals have been trained in trauma-informed instruction this summer, Carranza said. Still, dozens of principals in at least eight communities have publicly asked for a delay in the Sept. 10 reopening of buildings for myriad reasons, including to have more time to train staff on trauma-informed instruction.

The education department rolled out the curriculum with the help of First Lady Chirlane McCray, who has focused on mental health initiatives throughout Mayor Bill de Blasio’s tenure. She launched ThriveNYC, a citywide program aimed at eliminating stigmas around mental health and filling service gaps where needed. That program turned controversial amid criticism of wasteful spending and lack of clear metrics on the program’s effectiveness.

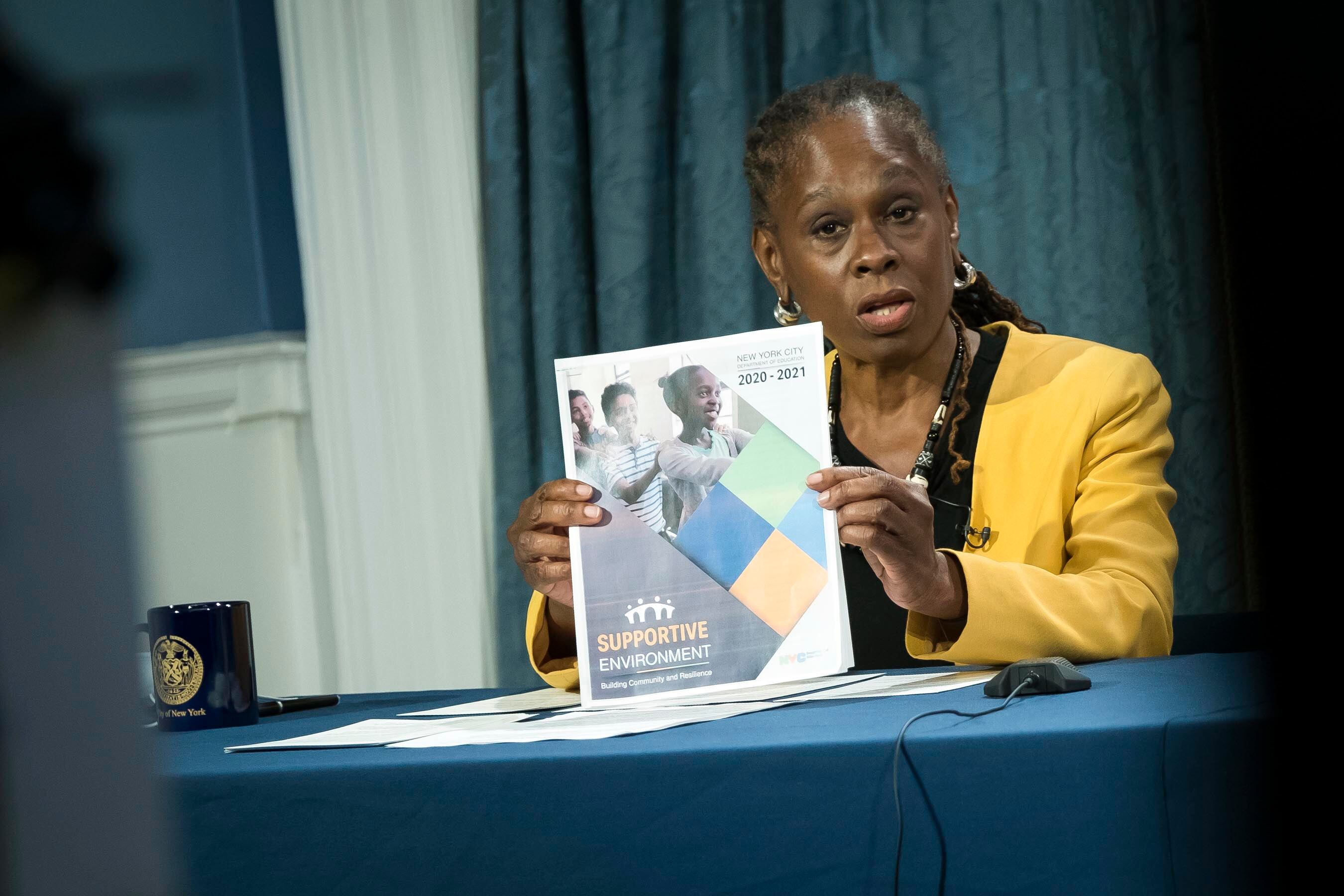

McCray — who held up a thick packet of curriculum materials during Wednesday’s announcement — was previously involved with a program announced last year promising to expand social emotional curriculum and training for elementary school teachers and restorative justice training at middle and high schools. (She said Wednesday that 5,000 teachers have been trained on those practices to date).

“On the first day of school our students will be carrying more than the usual weight of their backpacks — they’ll be carrying the weight of myriad emotions experienced over the last six months,” McCray said. “Can our educators ignore those feelings and just pull out a textbook? No, it’s not enough.”

But if the goal is to start the school year off with trauma-informed instruction, many educators don’t understand how they can get up to speed in the two days they have with their colleagues before schools welcome back students. It does not appear the trainings are mandatory, but the education department is recommending to principals they incorporate them.

“I think we need to learn about trauma-informed pedagogy and how to be good people to our students who have experienced trauma,” said Nate Stripp, an eighth grade social studies teacher at Brooklyn’s M.S. 50. “I don’t think we have the time or the mental space, really, to do that right now.”

Stripp and his colleagues are already steeped in social-emotional-informed instruction, even using a mood meter — a tool from McCray’s social emotional learning announcement last June — to help staff and counselors gauge students’ well-being during remote learning.

Still, this kind of work takes time, Stripp said, and he fears that educators will be consumed during the two days before students return “rushing to figure out what a radically different school year is going to look like.” Layered on top of that, many teachers will likely have intense emotions about being back and the possibility of a strike, he said. The teachers union has threatened labor action if the city does not meet their list of health and safety demands.

A department spokesperson said there is no expectation that all teachers will be trained before school starts, and training resources will be available throughout the fall. This new training builds off of a professional development series from the spring focused on grief, loss, and self-care, which trained more than 13,000 teachers, the spokesperson noted.

To cover the costs for training teachers, the Fund for Public Schools — the department’s fundraising arm — raised $1.9 million from nonprofit organizations focused on anti-poverty and youth-related initiatives including Robin Hood, the Tiger Foundation, and the Gray Foundation. The training curriculum was developed by the University of Chicago’s Trauma Responsive Educational Practices Project, the spokesperson said.

Additionally, the Child Mind Institute, a national nonprofit that focuses on youth and families dealing with mental health and learning disorders, will help staff a hotline for educators who have questions about these best social-emotional practices, officials said. This organization is also creating more training resources and classroom materials for schools.

Some advocates were heartened by the news. The new curriculum and training will “build a solid foundation” for teachers to understand student trauma as they return to buildings, said Dawn Yuster, director of the School Justice Project at Advocates for Children New York, which has advocated for restorative justice practices at schools.

But Yuster wants the department to ensure that school staff will know how to properly help students with the most profound mental health challenges and disabilities who experience emotional crises at school this year. These students may need a lot of additional support after months of remote learning, and she doesn’t want staff to respond by calling police.

The department has some experts at borough offices and schools, such as behavioral specialists and social workers, who are supposed to help teachers de-escalate mental health crises, she said. But borough offices alone saw $20 million in cuts this fiscal year, upon the request of City Council, and it remains unknown how those cuts fell. Yuster worries that some schools may not have access to such support workers. Given this year’s budget cuts, individual schools with smaller budgets may choose to let go of social workers or school counselors on staff.

“It’s really important that the city and the department of education have those professionals ready to be able to address crises when they occur,” she said.