Amid a steady upward climb in coronavirus cases, Mayor Bill de Blasio is sticking to the strict standard he has set for closing school buildings across the country’s largest school system.

Schools would close the day after the citywide positivity rate hits 3%, based on a seven-day average, the mayor said Thursday. That day appears imminent: The city’s average positivity has climbed to 2.6%, even as COVID-19 rates in schools have remained low. Random testing on campuses has shown just 0.18% positivity out of almost 112,000 tests conducted among students and staff.

There could be time to avoid school closures, the mayor said, urging people to double down on wearing masks and social distancing measures.

“There’s still a chance to do something to avert that,” de Blasio said. “And that’s why it’s so urgent that everyone does what we’re calling upon them to do, to help protect our schools.”

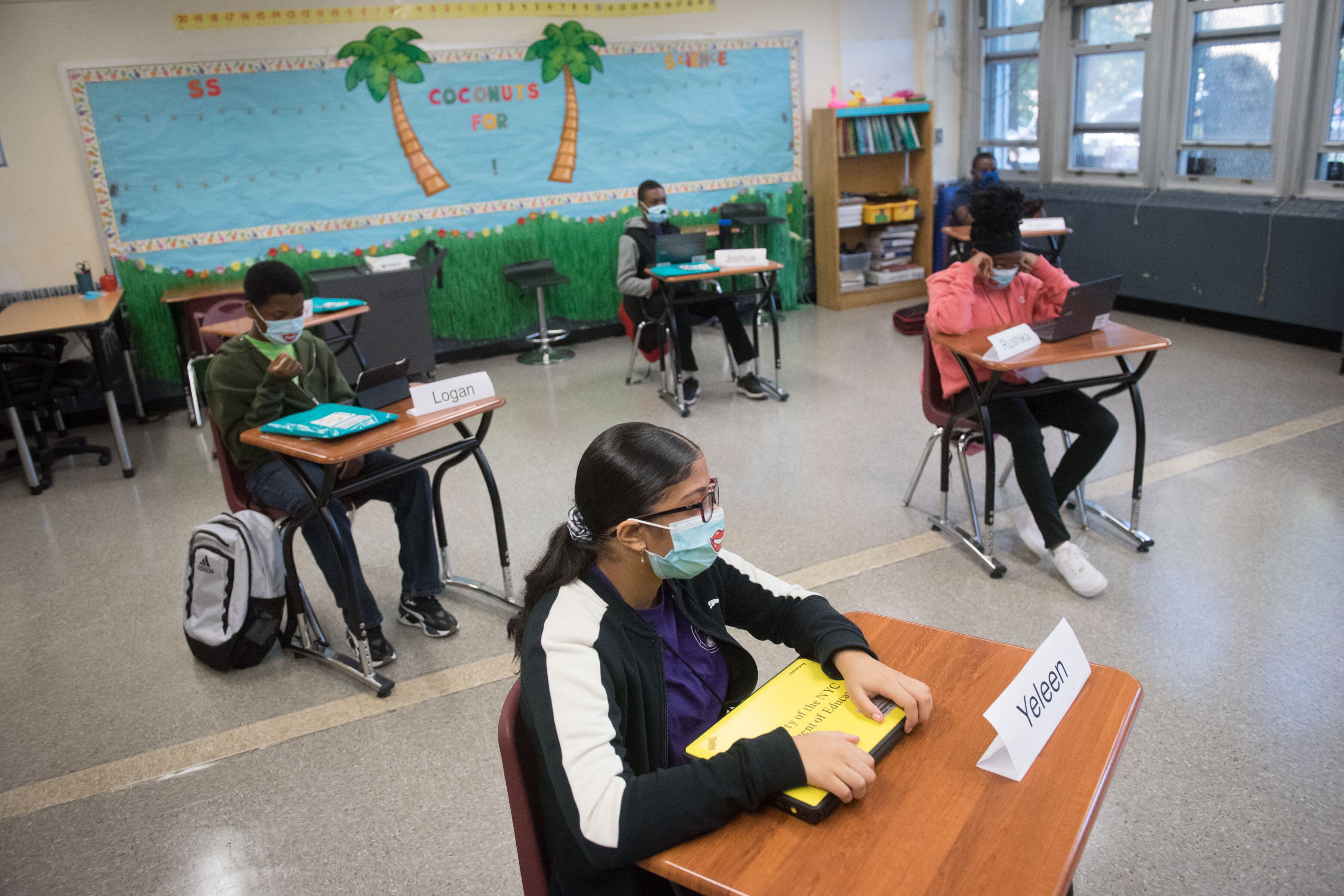

Currently, all students have the option of returning to school buildings, though social distancing requirements mean that most can only attend school between one and three days a week. But far fewer students than expected have gone back to classrooms. Out of roughly 1 million students enrolled in public schools, only about 280,000 have attended in-person classes at least once since the start of the school year.

Much remains up in the air about how another citywide shutdown would happen or what it would take to reopen school buildings. United Federation of Teachers President Michael Mulgrew said he would want to see the city’s positivity rate decrease for seven days and dip below 3% before returning to classrooms.

Here’s what we know about the city’s plans and what’s still being figured out.

The city isn’t planning to budge on its threshold for closing down school buildings.

The city established its criteria for closures this summer. New York City was not far removed from the trauma of the spring, when the city became the world’s epicenter of infections and deaths. De Blasio faced intense backlash to his plans to reopen the school system, with parents skeptical that their children would be kept safe and the teachers union threatening a strike.

The strict threshold for closing, along with a random COVID-19 testing program in schools, was largely seen as a way to convince families and teachers to return to buildings. Standing by it, de Blasio said, was “about keeping faith with everyone in all school communities.”

“We put a standard out to say to everyone, ‘We’ll have your back. We’re going to do this in a very rigorous fashion.’ We need to stick to that standard,” de Blasio said.

The mayor has championed opening the school system, arguing that in-person instruction can’t be matched by remote learning and that the city’s most vulnerable students and families rely on schools for care and meals.

Some elected officials, along with candidates who are running to replace the mayor in the next election, said the city should keep buildings open, citing increased testing capabilities and low transmission inside schools.

The city’s 3% threshold is far more conservative than the state, which allows schools to remain open so long as positivity rates stay below 9%. Whether New York City’s charter, private, and parochial schools would have to adhere to city rules or state ones remains a question that the mayor could not answer.

The World Health Organization, meanwhile, has recommended more general closures until cases dip below 5% for a 14-day period.

Anna Bershteyn, an assistant professor of population health at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine did not comment specifically on the city’s threshold for school closures but said that “acting early is a good strategy.” Doing so could shorten the length of any lockdowns, she said.

“The data show NYC clearly in a second wave. New restrictions are inevitable,” she wrote in an email. “A good threshold is one that unmistakably signals that a second wave is coming, but that isn’t so high that it comes too late.”

Other countries fending off a resurgence of the virus have kept schools open while shutting down other parts of society, such as office buildings and restaurants. On Wednesday, Gov. Andrew Cuomo imposed a curfew on some types of businesses, but some indoor dining is still allowed in New York City, and de Blasio said it would be up to the state to roll that back.

It remains to be seen if Cuomo will try to intervene in any school closures. He and the mayor have clashed on school decisions throughout the course of the pandemic, creating a confusing tangle of information for parents and educators.

If and when schools do reopen, things could look different.

How to open buildings has been a point of contention. Many parents, advocates, and elected officials spent the summer lobbying city leaders to prioritize in-person instruction for the youngest students and those most at risk for falling behind, including students with disabilities, those who are learning English as a new language, and those in temporary housing.

De Blasio suggested on Thursday that he would work with community leaders to craft the next set of reopening criteria, now that more is known about the role of schools and children in transmission, and how many families feel comfortable returning to classrooms. At least 54% of students opted to learn exclusively from home, with Black, Latino, and Asian students choosing to do so at higher rates than white students.

“Now we have a lot more information about what’s actually happening in the schools — a lot of valid questions, like what it might mean for younger kids versus older kids,” de Blasio said. “We’re going to work through and talk to all the stakeholders about what the comeback strategy would look like and how quickly we could achieve it.”

Many of the city’s large high schools are currently largely empty, according to Brooklyn Councilman Mark Treyger. The city shouldn’t wait to see if the virus continues to spread, but should start retooling its hybrid model now using the space available, he said.

“I want to build a system that prioritizes our most vulnerable kids who need in-person services,” Treyger said. “And that includes our younger students, students with special needs, multi-language learners, students in temporary housing.”

The city remained mum on child care for essential workers.

A systemwide school closure is likely to put essential workers — like grocery store clerks, sanitation crews, police, and medical professionals — in a deeper child care bind. The city is working on plans to support those families, but the mayor had nothing concrete to share.

“We do have to figure out how we’re going to support essential workers in that situation. We’ll come back with more on that quickly,” de Blasio said.

Providing child care to essential workers was a major sticking point in the spring, before the pandemic first forced school buildings to shut down. The city quickly opened up emergency child care centers for thousands of students.

The city’s plans to provide child care to fill the gaps left by the blended learning model have been slow moving. Leaning on community organizations to make room, officials have aimed to open 100,000 spots for students on the days they’re not in school buildings through a program called Learning Bridges. As of mid October, the city was still 80,000 seats short. A spokesman for the city said that more than 34,600 offers have been made to families who have applied for seats in the program, but did not say how many have accepted a spot.

Are we ready for another shutdown?

Gaping holes remain when it comes to access to the internet and devices to be able to log into remote learning. City officials are scrambling to equip homeless shelters with Wi-Fi, a project that won’t be completed until this summer. The city is also still distributing tens of thousands of devices that schools and students have requested.

Many New York City principals expected another citywide shutdown and planned this summer for such a possibility. One way is by having students in school buildings, who are logging into computers to watch lessons that teachers deliver remotely — meaning that their courses will change little if the city goes fully remote.

But there seems to have been little attention paid across the school system on how to improve remote learning, and many educators say they’ve been teaching themselves best practices and how to use a variety of tech platforms.

Mulgrew, the teachers union president, said there have been improvements in remote learning — but largely because of work happening at the school-level.

“I’ve been very vocal and critical of the department of education instructional people that they should have been doing a lot more,” Mulgrew said. “I don’t know why we have all these people who work in central, if it seems like they just tell schools to figure it out on their own.”

Still, the mayor said he was confident that schools and teachers are ready to make an abrupt shift to fully virtual learning, if needed.

“We’re already in a situation where principals and teachers knew that we could teach every child remote at any point, if we had to — literally the next day,” de Blasio said. “Everyone is being alerted to prepare for something.”