As next week’s Race to the Top deadline approaches, pro-charter advocates are marshaling all their resources to lift the state’s cap on charter schools. George Banning is one of their foot soldiers.

It’s been hard to miss the advocacy group Education Reform Now’s pro-charter, anti-teachers union ad blitz. The group, backed by millions of dollars raised largely from hedge fund managers, spent $750,000 on a television ad buy last week, for example. Its web ads plaster Google, Facebook and news websites.

But the group is also trying to rally support for its efforts in Albany by sending roughly 40 canvassers like Banning literally to voters’ doorsteps.

To persuade lawmakers to support their issues — many of which clash with the powerful teachers union — Education Reform Now has to argue that its positions enjoy a groundswell of public support. But the true extent of public support for its position is unclear. The last independent poll that asked found that more than 60 percent of New Yorkers wanted more charters, but that was in March 2009. A recent poll reported that public support for Chancellor Joel Klein, a charter school cheerleader, is declining.

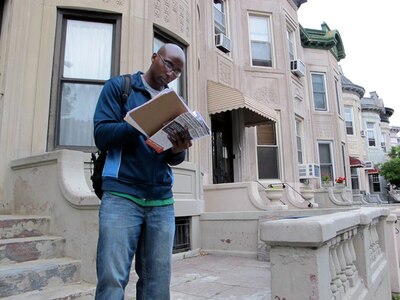

And so one afternoon last week, Banning hit the streets of the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn armed with postcards and petitions addressed to the neighborhood’s assemblyman and senator. On a clipboard, Banning carried a list of names and addresses of registered voters.

Face of the campaign

Banning is a tall man in his early 30s with a posture that gives away his history as a dance graduate of LaGuardia High School. After an injury, he gave up his dancing career, got an undergraduate degree in biology and is headed to medical school this fall. He got this job through connections made as a canvasser for Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s reelection campaign, and goes out canvassing five afternoons a week.

Each of the postcards Banning carried asked lawmakers to vote “yes” on a measure that would more than double the number of charters allowed in the state. Banning, who has canvassed in all the city’s borough’s except Staten Island, is also hoping to build support for an effort to do away with the city’s seniority-based layoff system.

The day I tagged along, Banning was covering friendly territory. Crown Heights’ Assemblyman, Karim Camara, introduced the cap lift bill that Education Reform Now supports and that the Senate already passed earlier this month. Banning also happened that day to be canvassing the neighborhood where he grew up; his elementary school, P.S. 161, was a few blocks away. (One man mentioned that his mother-in-law had taught there for many years. “Mrs. Alexis?” Banning replied excitedly. “I know her.”)

The roughly 15 voters who opened their doors for Banning in Crown Heights in a three-and-a-half hour canvassing shift are clearly not a representative sample. But their responses to Banning’s pitch suggest that at the very least, the lobby’s public relations campaign has succeeded in capturing attention, if not creating deep knowledge of the issue.

Banning’s script typically went like this: First, he introduced himself as a representative of a pro-charter advocacy group and assured that no, he was not with the census. Banning then asked if the person knew that New York had lost $700 million because state lawmakers had not lifted the cap on charter schools.

Responses varied:

— “I saw the commercials, but I don’t know the politics of it.”

— (Blank stare.)

— “Is that what they were showing ads for on the TV?”

—”Mayor Bloomberg came to my church Sunday talking about this, so what the heck!”

— “What does Karim think of this?”

— “Is this that $700 million thing?”

Making the pitch

For some of Ed Reform Now’s canvassers, it’s just a job, Banning told me, but he’s a true believer. Banning is the father of a student at Excellence Charter School and has a personable, persuasive manner as he explains that he thinks all parents deserve strong public school choices, including charter schools, for their children.

He convinced most voters he encountered to sign their names and addresses to pro-charter school postcards with relative ease, often arguing that doing so would help the state secure the $700 million Race to the Top funds state officials argue New York’s schools desperately need. “Anything for the kids,” several people said as they signed without asking questions.

Not everyone was so amiable. “So we’re going to sell ourselves to Washington for this?” asked one man, suspicious of the federal government’s push to dangle funds as a way of influencing state educational policy. He took a flier but did not sign.

If he secured a signature on a pro-charter school postcard, Banning moved to stage two. “Also, have you heard about the crisis in Albany with budget cuts?” he asked. (“Which one?” one woman deadpanned.) Around 6,400 teachers face layoffs, he explained. “That’s really sad,” he said, “and what’s more sad is that they’re going to fire first the teachers who have been hired most recently.”

“Do you think that’s fair?” he asked.

“I’m on the fence about this,” responded Ann Rollins Boyd, the mother of a P.S. 161 student who had signed Banning’s charter school postcard. “In the corporate sector when they downsize, that’s how they do it, too.” Banning pushed, and Boyd eventually assented that she thought there should be a way to pinpoint the best teachers and spare them. She signed the petition.

At one house with day care signs in the window and mail from the national teachers union peeking out of the mailbox, Banning got a surprising answer. “No, I don’t think that’s fair,” said the middle-aged teacher who answered the door. “I’m not supposed to sign this, but I’m going to,” she said.

The last visit of Banning’s run was also the only one where Banning encountered serious opposition. “This, to me, is a jaded issue,” said Jason Hayes, a filmmaker and former teacher. “If you’re giving people a choice between a charter school that’s extremely well funded and a public school that’s extremely underfunded, what kind of a choice is that?”

Banning spent the next 20 minutes trying to convince Hayes that charter schools don’t weed out students and are not a form of privatizing public education, and that the push against seniority-based layoffs is not a union-busting strategy. It didn’t work. “At the end of the day, this campaign for me is not about educating kids in the best possible way,” Hayes concluded.

But Hayes’ opposition won’t show up in Education Reform Now’s records. Later on the train, as Banning tallied all of the responses he’d received on a scale of 1 (signed a petition) to 5 (extremely opposed), I noticed that he didn’t include Hayes at all. He wasn’t the registered voter at that address and so wouldn’t be counted, Banning explained.

I asked how Banning would have rated Hayes if he had been the voter at that house. To my surprise, Banning told me he would rate Hayes as a 3.

He seemed pretty opposed, I said.

“He took some literature,” Banning said optimistically. “And he said he’d think about it. Maybe he’ll change his mind.”