Charter schools receive less public funding per student than their district school peers, according to a report released today by the city’s Independent Budget Office.

But the size of that disparity varies widely according to whether the charter school is housed in a city-owned building, the report said.

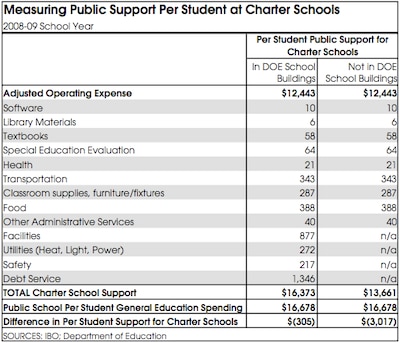

Charter schools that are housed in public school buildings receive only $300 less per student than district schools, according to the IBO’s calculations.

But charter schools that own their own buildings or lease them receive more than $3,000 less per student in public funding than district schools, the report said. In those schools, charters must pay for maintenance and other building costs themselves. Those costs are covered by the Department of Education for charters in city-owned buildings.

The report, prepared at the request of Panel for Educational Policy member Patrick Sullivan, is an attempt to resolve a long-standing question in the charter school debate.

Charter school advocates argue that, under the state’s funding formula, the schools receive significantly less per student. Critics counter that charter schools, especially those housed in city-owned buildings, receive many hidden subsidies that either equalize or boost charter school resources above what district schools receive.

Both supporters and critics of the city’s charter schools found elements in the report to support their positions.

“The IBO study validates the City’s policy of offering public space to charter schools in an attempt to provide charter school students with the same resources as their peers in other public schools,” Chancellor Joel Klein said in a statement.

Charter schools are not legally guaranteed space in public buildings, but the Bloomberg administration, which strongly supports the schools, has offered space in district schools to many charters.

James Merriman, head of the New York City Charter Center, said the report bolstered charter advocates’ claim that charter schools are slighted by the state’s funding formula. “When you add it up, the gap between district schools and charters isn’t even close, particularly for those charters that do not share public space,” he said.

Teachers union chief Michael Mulgrew disputed that interpretation.

“The difference between funding for public schools and charter schools in public buildings is negligible,” Mulgrew said. “When you add in the private funding that many charter schools get, I’m sure that we’ll find that many charter schools have resources that are well beyond those of public schools.”

At the same time, both charter school opponents and advocates also found nits to pick with the report’s analysis, claiming that it either inflated or understated the amount of public funding charter schools receive.

Parent advocate Leonie Haimson said that the IBO’s accounting of district schools’ per-pupil spending includes DOE central administrative expenses that are spent on things like data systems and consultants.

“A lot of it is being spent by DOE on highly questionable priorities that don’t really benefit students,” Haimson said. “How much do we actually see at the school level? That’s the disparity we are talking about.”

By contrast, the Charter School Center released a statement arguing that many charter schools in fact receive far less money at the school level than district schools serving the same neighborhood. “[B]ecause the City has rightly directed more resources to district schools in high needs neighborhoods, the gap for charter schools in those same neighborhoods is much wider,” the statement said.

Because of the complicated ways charter schools and district schools are funded, a fair comparison of how much money district and charter schools actually spend on students is difficult to draw cleanly.

The IBO accounting of district schools’ per-student spending did include most central administrative costs, and the amount of money actually doled out to schools varies significantly from school to school depending on what students are enrolled at the school. Charter schools receive a flat per-student amount of public funding, but most of their administrative costs also come out of that fund. In the case of schools housed in city-owned buildings, some maintenance costs are then covered by the city.

The report did not examine the amount that charter schools raise through private philanthropy each year. According to an analysis by Kim Gittleson, a research assistant employed by one of GothamSchools’ funders, Ken Hirsh, charter schools in the city spent on average $14,456 per student. That number is greater than the amount of public support charter schools receive but still less than the amount of citywide per-pupil spending for district schools.

Questions of how charter schools are funded, and the effect of the city’s practice of granting public building space to charters, are currently under heavy public scrutiny. Charter advocates are currently lobbying legislators to lift a freeze on charter school funding that keeps spending capped at 2008-09 levels. And a rancorous debate over the city’s charter school siting practices has been cited as one of the biggest political obstacles to raising the statewide cap on charter schools.

In his statement, Klein linked those two issues, indicating that the city’s siting practices for charters are likely to remain unchanged.

“Until the state’s funding formula is revised and charter schools are eligible for capital dollars like other schools, we will continue to work with communities and parents across the City to find space for new charters when it is available and presents the right fit with other schools in a building,” he said.

The full report is below: