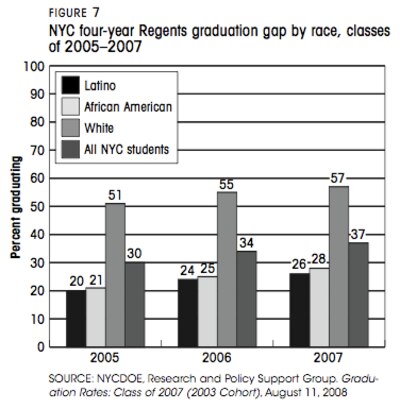

If the graduation requirements in effect for this year’s ninth-graders had applied to students who entered high school five years ago, the city’s graduation rate would be just 37 percent.

The new, more stringent requirements could cause the city’s graduation rate, which has only recently topped 50 percent, to plummet, advocates say in a new report (pdf) about what they call a “looming crisis” for the city schools. The report, prepared by the Coalition for Educational Justice, a parent group, details how poor and minority students could suffer most under the new rules.

Beginning with this year’s freshman class, all high school students will have to earn what’s called a Regents diploma by scoring 65 or higher on five different state exams. Until now, the state has allowed students who scored between 55 and 64 on any of the tests to graduate with a less rigorous diploma. The less rigorous diploma, called a local diploma, has been the most common type earned by city students.

At a press conference on the steps of the Department of Education this morning, CEJ and dozens of other advocates called for an emergency working group of state and city education officials to focus on how to help schools where few students are on track to graduate with Regents diplomas.

CEJ is also calling for a longer school day at low-performing schools, which it says should be turned into “community schools” that also offer health care, psychological counseling, and adult education. (A community schools coalition launched last year, backed by teachers union president Randi Weingarten. Her union, the United Federation of Teachers, has signed on to CEJ’s recommendations.)

“What you’re asking for for our children is totally reasonable,” said Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer, who was one of a number of elected officials who made brief appearances at the rally.

This is not the first time that CEJ has called for strengthened academic standards at city schools. Last year, the group pushed the DOE to direct more attention toward low-performing middle schools.

The DOE has put in place new programs for those schools through its Middle School Success Initiative, but it has not mandated the three main elements of CEJ’s proposal: extended day programs, support for new teachers, and more professional counselors.

Sabrina King, the administrator leading the DOE’s middle school initiatives, told me today that the actions the department did take, including adding Regents-level courses to more middle schools, were made with the tougher high school graduation requirements in mind.

“Student performance in eighth grade is a predictor of high school graduation, so we knew we had to start early,” King said. “Otherwise, [students] don’t have a fighting chance.”

King said she wasn’t in a position to convene a committee to study low-performing high schools, as CEJ calls for. But she said some of CEJ’s recommendations could help more students graduate.

“An extended day, if implemented right, can make a difference,” she said.

Once city high school students go on to college, the effects of not being required to perform at a high level become clear.

“I started college this fall and I feel totally unprepared,” said Fatoumatah Magassa, a Hunter College student who graduated last year from Manhattan’s Bayard Rustin High School. Bayard Rustin is one of the schools the DOE this year announced would close due to poor performance.