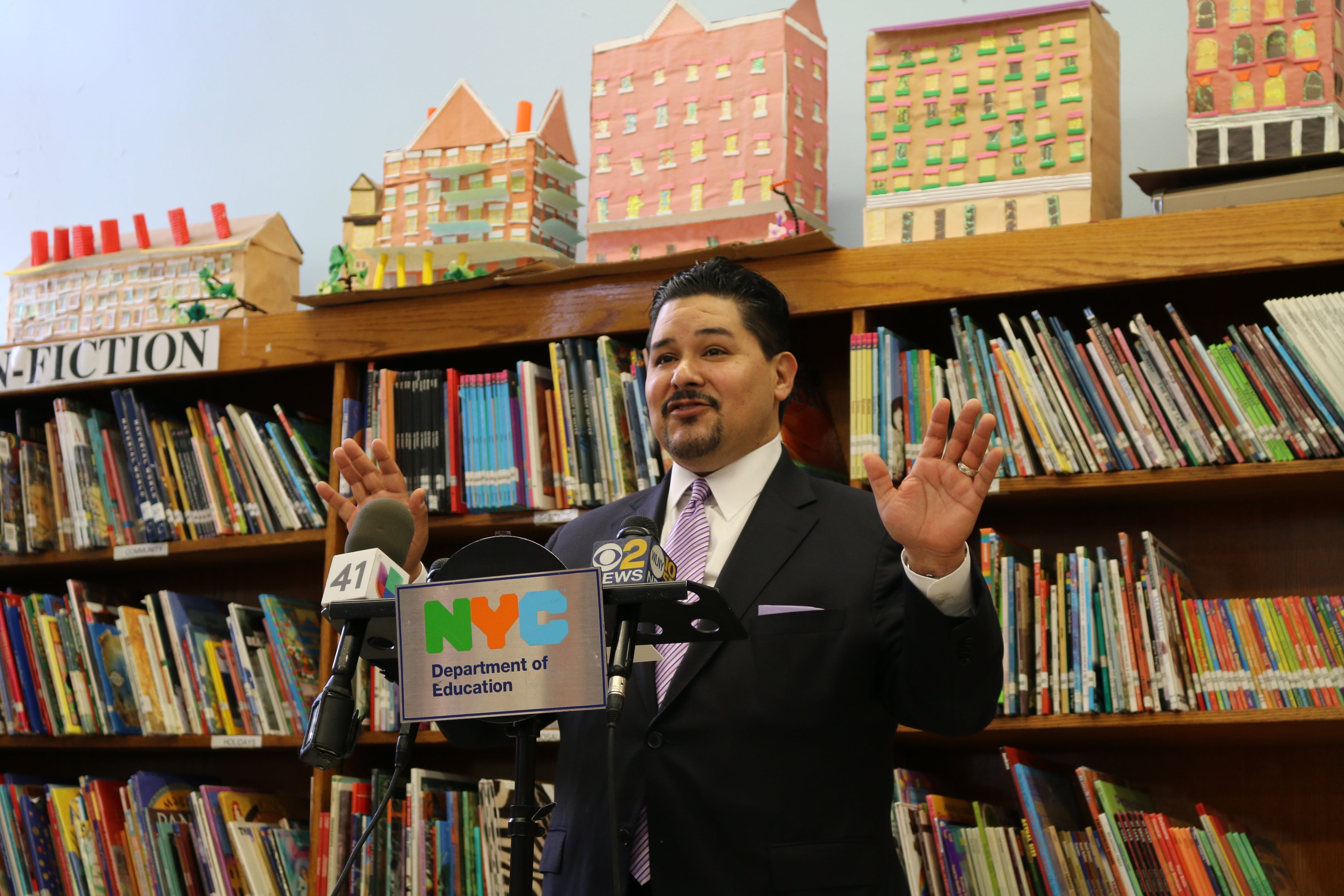

The education department might allow families more than one opportunity to switch to in-person learning from fully-virtual classes, Chancellor Richard Carranza said Thursday — injecting uncertainty into an announcement made three days earlier that there would be one chance this school year to change.

On top of that, with far fewer students returning to classrooms than the city anticipated, certain schools may soon be able to offer more days of in-person learning, he said.

Carranza’s message to members of his parent advisory council, some of whom were visibly frustrated, was simple: “Change is the only thing that we can count on.” He suggested that changes in the trajectory of the coronavirus, or the availability of a vaccine, could alter the city’s plan to offer just one opportunity to opt for in-person schooling.

“If it’s possible, and if it makes sense, we can absolutely consider another time period where students and families can opt back in,” Carranza told parents, one of whom accused him of breaking his promise that families would have the opportunity each quarter to switch to in-person learning.

“I’m not breaking any promises — I’ve been very clear from the beginning that circumstances change,” Carranza said.

Some members of the chancellor’s parent advisory group pointed out that the latest controversy of shifting the deadline for returning to buildings fits a broader pattern of the city changing policy with little notice or time for families to plan. On top of two last-minute delays to the start of the year, the city also changed how much live instruction students are entitled to, among other shifts.

Officials were hoping that a single window to opt for in-person learning — from Nov. 2 to Nov. 15 — would give them a clearer sense of how many students actually want to return to their school buildings. Students would be allowed to start in-person learning between Nov. 30 and Dec. 11. If there isn’t an influx of students, that could allow some schools to offer four or five days a week of in-person instruction because they won’t have to leave space for students whose return is uncertain, Carranza said. A spokesperson said some schools have already begun to do that, though did not immediately say how many.

City officials previously assumed that all families who didn’t formally fill out a form for virtual learning would send their children back to school buildings. Of the city’s roughly 1 million students (a number based on last year’s enrollment), a little more than half opted for fully virtual instruction as of last week. Officials estimated that the rest were part of the city’s hybrid model, attending school buildings one to three days a week, for the most part.

But Carranza acknowledged on Thursday that assumption was incorrect: Only 280,000 students have attended in-person classes at least once — or roughly a quarter of the city’s students. That translates to about 180,000 fewer than the city claimed.

“The number of students that we planned for in person has not materialized,” Carranza said. “It may be the way we surveyed.”

That has left many classrooms with a tiny number of students and presents a logistical problem for principals. School leaders must leave space for students who never explicitly choose fully-remote learning in case they decide to return and have to figure out how to cover potentially higher numbers of remote learners.

It also has significant financial implications: The city could be spending an estimated $32 million a week more than normal to keep buildings open with new health protocols, according to an Independent Budget Office analysis. Carranza also suggested the city may have hired substitutes that weren’t necessarily needed because so few students showed up in person.

The decision to offer just one opportunity to opt for in-person learning was based on feedback from principals, city officials have said. Some school leaders, however, disagreed with the department’s policy. The union representing principals was not consulted, a union spokesperson said. The teachers union also criticized the policy.

Pat Finley, co-principal at the Metropolitan Expeditionary Learning School in Queens, a middle and high school, said his parents have been panicking about having to make a decision for the rest of the school year, especially since infection rates could fluctuate significantly or a vaccine could be available.

“The idea that I should tell parents they have to project six months into the future when so many things could change — it doesn’t seem fair,” he said.