Updated — Thousands of teachers, parents, students and advocates headed to Albany Wednesday, hoping to influence state-level education policy debates with a giant rally focused on the city’s struggling schools and a smaller effort from the teachers union to lobby legislators for more funding.

Geoff spent the day with a group of students and parents from Success Academy Charter Schools, and Patrick spent his with a contingent from the United Federation of Teachers.

Here’s what the day looked like from their eyes. (Looking to catch up on the issues? We explained what both sides are looking for — and what to expect from the spectacle — here.)

By the time this coach bus departed from its first stop outside the teachers union headquarters in Lower Manhattan at 6:50 a.m. Wednesday morning, its five passengers were already on message.

The three parents and two teachers are among 1,100 the United Federation of Teachers expects to send to Albany today to lobby lawmakers to up city school funding by $2.2 billion. As the bus headed north to Harlem to pick up more amateur lobbyists, the early-bird group was already complaining about the need for taxpaying parents to plead with lawmakers to give their schools more money.

“I am just tired of begging,” said Tesa Wilson, a public school parent and recent hire in the UFT’s office of community and parent outreach. She’s the UFT-appointed captain of the bus. “If you give us money, parents will not have to be reduce to paupers with our hands out all the time.” T. Elzora Cleveland, a member of the city’s Panel for Educational Policy and an accountant who took the day off work to lobby, nodded vigorously. Some city schools still don’t have basic services, like wireless Internet, she said. “Come on, Starbucks and McDonald’s are ahead of us?” she said, noting those chains’ ubiquitous WiFi access. “This is out of control.”

Lisbeth Torres, a parent from Glendale, Queens, whose children attend P.S. 91 and I.S. 119, agreed. Later, she explained how the P.S. 91’s parent and teacher leadership team raises money through raffles, dances, and luncheons to help teachers afford basic supplies, like printer paper and dry-erase markers. She said she personally spends about $150 at the start of each school year to help supply her children’s classrooms. Her planned message to lawmakers today: “Provide more funding,” she said. “We need it.”

By 7:30 a.m., the bus had pulled up to the Adam Clayton Powell State Office Building in Harlem, and about 15 NAACP members and 20 parents piled on. Wilson welcomed them and pointed out the trays of muffins and bagels and the juice and water. (No coffee was provided, as this reporter was quick to note.)

“Good morning, this is your bus to Albany!” said Wilson, who before joining the UFT last month was a member of the community education council in Brooklyn’s District 14 for a decade. As the bus finally hit the road to Albany, Wilson led the passengers in a prayer asking for a safe journey. She emphasized the importance of their mission. “We are on a righteous course this morning,” she told the group. “Speaking truth to power.”

Moments later, the bus stopped at a traffic light outside Success Academy Charter Schools’ Harlem 1 campus, reminding the passengers what they were up against. Perhaps the union’s fiercest political enemy, Success closed its schools Wednesday so teachers and parents could attend a pro-charter school rally in Albany. But if the union plans to criticize the charters today in Albany, Wilson said she was going to hold back.

“I promised to use my Sunday morning language today,” she said.

—Patrick Wall

A lot is made of the Success Academy charter school network’s decision to close schools so that parents and students can participate in political rallies.

To many, the scheduling decision gives the perception that students miss learning time for politics, and that it essentially requires parents and students to attend. But Success officials have said the rallies are no different from field trips, that their students stay busy on the bus rides with schoolwork, and that parents are under no obligation to attend.

The network’s goal was for 85 percent of parents or guardians to RSVP. Fort Greene Success, whose bus this reporter is taking up to Albany, hit 77 percent one week ago, ranking it third in the network. “She was surprised” in a good way, new Principal Candido Brown said of Success Academy CEO Eva Moskowitz’s reaction to his numbers.

On one of the five buses that departed from Fort Greene Success, a second-year school serving kindergarten through second grade, schoolwork was encouraged but not required. A few students and their parents worked on a packet printed for the ride up. They called it “school on the bus,” and it includes minute-long addition and subtraction problems (for first graders), two comprehension exercises (“What is the Solar System?” and “Two Kinds of Whales”) and a personal reflection section for students to describe their day.

About 45 minutes into the ride, parents and teachers stood up to talk about why they were traveling to Albany.

Erica Robinson, a parent from East New York, said she was discouraged by her high-school counselor from pursuing a nursing certification, something she said was emblematic of the schools that many students living in New York City have access to.

Georgia Swan-Ambrose, a special education teacher, said she started her teaching career at a troubled middle school in Baltimore before helping to open Fort Greene Success. She choked up as she named some of her former students, who she said were let down by their school.

About two hours into the ride, Lashuana Flowers read aloud from the picture book “A Smell of Sweet Roses” by Angela Johnson, about Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Students gathered in the middle of the bus, where she gave them prompts to turn and talk to one another. “What was Dr. King rallying for?” she asked.

Meanwhile, Nadia Molinari, the school’s parent council president, explained that some parents and students were absent for a variety of reasons. One parent is a paraprofessional at a Department of Education school who couldn’t take the day off, she said. Another parent who she was texting with this morning was still on the fence, Molinari said.

“It’s more like we put pressure on the parents to come,” said Molinari, a parent who has to take two bus lines and a subway to get her daughter to school each day. The rallies as necessary for her school’s existence, she said.

Erica Robinson, another parent from East New York, agreed. She said she loves the Fort Greene Success because it’s taught her daughter Chloe social skills and instilled in her a love of learning.

— Geoff Decker

This bus — one of 32 the UFT is sending to Albany today — is mostly filled with parents. But there’s also a contingent of NAACP members aboard who plan to lobby lawmakers on a range of issues today, from housing to healthcare to education.

Geoffrey Eaton, president of the NAACP’s mid-Manhattan chapter, said he agrees with the teachers union on most issues, though his take might be a little more nuanced.

For instance, he said he supports parents’ ability to choose to send their children to charter schools. However, since the vast majority of New York City students attend district schools, he said the NAACP is focused on them today.

“We don’t have anything against charter schools — it’s parent choice,” he said. “But we’re here to lobby for the 96 percent.”

He also said he supports the job protections that the union fights for on behalf of teachers, such as tenure and due process before they can be fired. Still, he backs strong evaluations that will help “weed out” poor-performing teachers and thinks that educators’ salaries should be raised and their training improved in order to attract more top college graduates to the profession.

“We need to keep union protections,” he said, “but raise the bar.”

— Patrick Wall

A sea of red brightened what would have otherwise been another gray winter day in Albany.

Thousands of people flooded the park on the east side of the Capitol building, donning red-colored garb that branded this year’s massive political rally organized by charter school operators.

The message was clear, but broad: Too many schools are failing and parents don’t have enough options to send their kid elsewhere. At the base of the Capitol’s steps, Lt. Gov. Kathy Hochul and several state lawmakers from the Bronx echoed that sentiment.

Unlike the many parents the message was catered for, Crystal Davenport, whose son is a first grade student at Fort Greene Success, said she had the choice to send her son to other well-regarded schools in District 13.

Davenport said she doesn’t consider herself among those who have been historically underserved in urban public education, but added that political rallies such as today’s are crucial to bringing awareness to the issue.

“I’m here for other kids who don’t have this option,” she said.

The day’s highlight came after the political speeches and student performances were wrapped up, with a performance from Grammy-award winning singer Ashanti, who replaced Janelle Monáe at the last minute.

— Geoff Decker

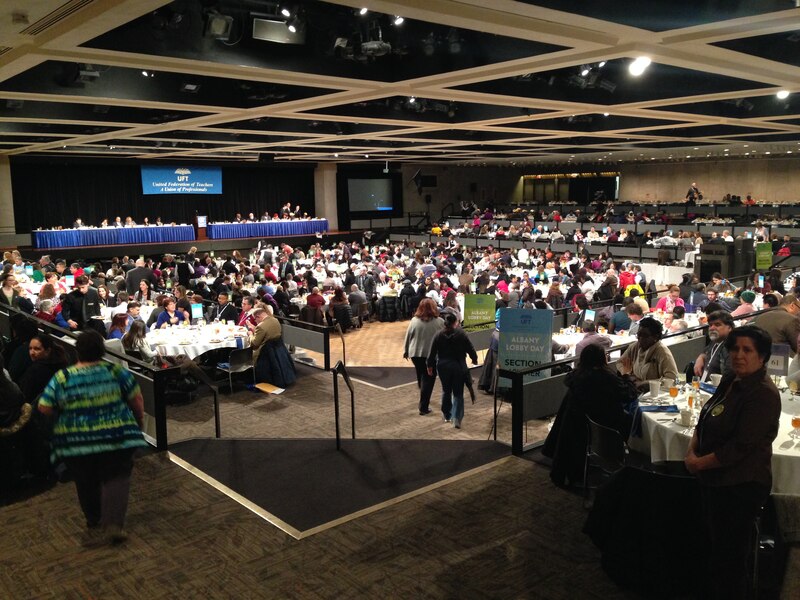

While teachers who had come to lobby with the teachers union dined on grilled chicken and salad this afternoon, UFT President Michael Mulgrew took a few minutes to pump up the crowd.

He told them to bring the passion they have in the classroom to their meetings with lawmakers.

“Are you ready to tell them why the governor’s proposals are just plain wrong?”

Mulgrew then mentioned the charter school rally going on outside. The union would never have brought students along to lobby with them, he said.

“We don’t use children as props,” he said. “We would never think it’s a good idea to put a child on a bus for six hours in the middle of the winter.”

Then Mulgrew introduced Assemblyman Carl Heastie, who recently replaced the union’s close ally Sheldon Silver as assembly speaker. Heastie read prepared remarks for a few minutes, then said he was going to speak off-the-cuff.

“I know that we’re in a very, very tough situation with a governor who wants reforms,” Heastie began, saying he tried to remind Gov. Andrew Cuomo “of the difficult situations that teachers face.”

He then suggested that he has some reservations about two of Cuomo’s most contested proposals: tying teacher evaluations more closely to student test scores, and letting outside groups take over struggling schools.

“There are other factors that should be considered when you look at why schools don’t perform,” he said, noting that some students face serious problems outside of school. “To me, it is unfair to blame teachers.”

Assemblywoman Cathy Nolan said that even with the change of leadership, the Assembly still backs teachers and their priorities. Alluding to the rally outside, she said, “There are many people, including some here today, who feel very different than we do about the future of education.”

The fact that teachers had traveled to the Capitol to share their classroom stories would stick with lawmakers as they debate this year’s budget and the governor’s controversial education proposals, Nolan added.

“Your presence here makes a difference,” she said.

After lunch, Mulgrew and several teachers from the city’s growing PROSE program met privately with Nolan on the assembly floor.

The program allows schools to bend city and contract rules in order to experiment with different approaches to things like class sizes and school scheduling. The teachers each told Nolan about the changes their school made through the program, which included 62 schools last year but could soon expand to include about 200 over five years.

Rob Carp, a teacher at Community Health Academy of the Heights, said the program allowed his school to tweak its schedule so that teachers have more time to meet and talk about students’ academic and personal needs. He said one student who had been severely depressed has been doing much better in class now that teachers have more time to plan ways to address his emotional needs.

“We’re dealing with the kids who usually fall through the cracks,” Carp said after the meeting, which was not open to reporters.

Betty Nieves, an English teacher at the School of Integrated Learning in Crown Heights (which Chancellor Carmen Fariña visited Tuesday) explained how her school puts up to 40 middle school students in one class. That allows teachers to then pull out smaller groups and work on targeted lessons, she said.

— Patrick Wall

If the point of the UFT’s trip to Albany Wednesday was to let lawmakers know which issues matter most to teachers, then the 25 or so educators from District 21 in southern Brooklyn certainly did their job. If it was to recruit those lawmakers to back their cause, well, the one they chose didn’t need much convincing.

As UFT President Michael Mulgrew and the union’s strongest allies in Albany addressed members during lunch this afternoon, the District 21 crew met their local assemblyman, William Colton, in the hallway to make their case. But even before the teachers could share their concerns, Colton let them know he was on their side

Colton said Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s plan to tie increased school funding to a raft of contentious policies – including teacher evaluations tied more closely to student test scores – represents “a full frontal attack on public education.” He said the city is owed billions in increased education funding from the settlement of a landmark lawsuit, and added that the money should be used to lower class sizes, buy technology for schools, and create after-school programs.

“We have to start making demands,” Colton told the teachers from Coney Island and Brighton Beach, “and fighting back.”

Then it was the teachers’ turn.

Theresa Cardazone, a teacher at I.S. 281, held up with a blue UFT packet that she said contained 200 student letters detailing the difficulties of sharing their building with a charter school, Coney Island Prep. The charter students have iPads, air-conditioned classrooms, and specially-ordered organic lunch options that make her own students envious, Cardazone said after the meeting.

“It’s so frustrating,” she said.

Seth Wolchok, a prekindergarten teacher at P.S. 97, explained that overcrowding has forced all three of the school’s pre-K classes into outdoor trailers. The four-year-olds have their reading and math lessons and eat lunch in the trailer classrooms, but must bundle up and head into the main building for art and music, Wolchok said.

“There’s no room for proper pre-K at our school,” he told Colton.

Jackie Herman, an advanced-science teacher at I.S. 98, said the middle school has class sizes of up to 35 students. (She later explained that teachers at the school agreed to lift the school’s class-size cap to meet demand and to prevent the city from moving other schools into their building.) Still, she said such large classes are not ideal for students.

“It works way better when you have 25 or 22,” she told the assemblyman.

Then the teachers thanked the lawmaker and headed back into the conference hall for lunch. After all that lobbying, they were ready to eat.

— Patrick Wall

The trip to Albany from Fort Greene Success Academy wasn’t perfect for the roughly three dozen staff, students and parents who rode together for Wednesday’s rally.

The DVD player wasn’t working, for instance, so children wouldn’t get to see “Waiting for Superman,” a documentary about the long odds that Harlem parents face to win a seat in one of the neighborhood’s charter schools.

But more important was that they accomplished what they set out to do in Albany, said Georgia Swan-Ambrose, a special education teacher.

“Behind all of those windows were all of our representatives,” Swan-Ambrose said, referring to the Capitol building, where the rally was held. “That’s political power. We matter.”

“It was important for them to see us there,” she added.

The group rehashed the day’s events over Subway sandwiches as their bus pulled out of Albany. Principal Candido Brown had kept mostly quiet on the ride up during discussions about why they were attending the rally, but he was more vocal in the afternoon.

Brown is the third principal at Fort Greene Success since the school opened just 18 months ago. He was 49 days into the job, he said, and wanted to use the event as a mini-rally for the school.

“We are in this together,” Brown said.

—Geoff Decker