Jan. 1, 2014 marked more than a new year for New York City: We got a new mayor, a new schools chancellor, and a new vision for improving public education. Bill de Blasio won $300 million for early childhood education, forged a new nine-year contract with the city’s teachers, and made sweeping promises to do away with the entire ethos of Mayor Bloomberg’s tenure.

In other words, this was a year of big shifts, not small tweaks. After 12 months of analyzing the changes, here’s our annual roundup of the big lessons learned from covering city schools.

1. What was out is in again.

When Bill de Blasio picked Carmen Fariña to be his chancellor, eight years had passed since she had left her job at the Department of Education, and a lot had changed. But her selection, de Blasio said, also came with a promise that she would usher in a friendlier era of education policy that harkened back to the years before Bloomberg. “It’s time to treat all members of the educational community like they matter again,” the mayor said.

Fariña, a career educator, was welcomed with a standing ovation from principals, and she promised to “review everything,” indicating that she would work to dial back some of the test-based accountability focus that had built up over the previous 12 years. “They tell me 70 is the new 40,” she said.

In a lengthy interview, Fariña promised a renewed focus on professional development and instructional approaches that were more common during her last stint. Within two months, she brought back a division of teaching and learning and an office for professional development, both of which had been dissolved after she left. New experience requirements for principals and superintendents marked a re-prioritization of time spent in schools and classrooms.

We mined Fariña’s past for clues about how she would handle the continued Common Core rollout and her book for her views on school improvement. And as she promoted a longtime deputy and appointed a longtime principal to top posts, high-level Bloomberg officials left in quick succession.

There were a number of seismic changes. For the first time in four years, the city did not begin the process of forcing any schools to close, though many schools continued to phase out this year. Changes to student promotion policy, teacher evaluations, and school accountability helped calm the waters around the role testing plays in school. De Blasio increased arts funding for the first time in years, and Fariña hired hundreds of guidance counselors and helped shepherd in an expansion of after-school programs, all of which had frequently faced the budget axe under Bloomberg. And 2015 promises to bring a rethinking of school support that de-emphasizes or dissolves networks and elevates superintendents.

2. But some things never change.

More than 6,300 classrooms were overcrowded this fall, continuing a long-time trend. (Different was the union’s response: A mention in an article in the union’s newspaper, rather than an inflammatory press conference.) The rollout of the Common Core standards continued with support from city officials. Many principals, teachers and parents continue to be outraged by the state’s testing policies and opted their children out of the spring tests.

Admissions to kindergarten, middle school, and high school continued to vex parents and students. Suspensions remained high, and no changes have come to the city’s discipline policies, though Fariña has promised shifts in the future. Fariña has promoted and expanded the previous administration’s work to improve academics and engagement among middle schoolers.

3. De Blasio knew what he wanted on education and got it.

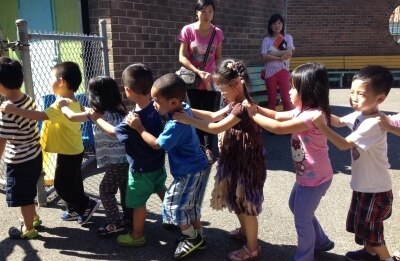

Bill de Blasio devoted much of his first nine months to fulfilling a signature campaign promise: to expand pre-kindergarten and after-school programs on an ambitious timeline at $530 million per year. To pull it off, his team coordinated an all-hands-on-deck lobbying campaign to win approval from state lawmakers.

De Blasio’s plan took some hits in state budget negotiations — Cuomo opposed an income tax that de Blasio wanted to fund the programs — but the city emerged with enough money to move forward. Though there were some hiccups, like a handful of late openings and some ominous warnings about contracts and quality, the complicated rollout has been smooth.

There are still plenty of challenges ahead, including ensuring that all of the programs run by outside organizations are up to snuff. The city is already at work preparing to create 20,000 more full-day seats to reach its goal of 73,300 available full-day seats, and working to find (and train, and evaluate) the necessary teachers — including some who are willing to accept the lower salaries that come with teaching pre-K through a community organization. Whether the early education gains pay off in the long term will be the ultimate question.

4. But on struggling schools, the administration’s vision was fuzzier.

De Blasio made it clear from the start that closing schools wouldn’t be his go-to strategy for improving schools, but a new approach took a while to come into view. Rumors swirled that the city would be corralling struggling schools into a special district and flooding them with support and resources, but details remained thin even as the school year got underway and as the state applied pressure for the city to move faster.

The delay stoked criticism from advocates and questions from other observers who had seen low-performing schools receive intense attention from the previous administration. At Boys and Girls High School, one of two high schools designated as “out of time” because they had struggled for so long, the outspoken principal complained that the education department’s plan was “doomed to fail.”

Behind the scenes, the city was making changes. It agreed to stop sending students in the middle of the year to the two out-of-time schools and even encouraged some students to transfer to other schools because they were behind in credits. It lured a new principal, Michael Wiltshire, to take over at Boys and Girls. And a city-union deal will require staff members at Boys and Girls and Automotive High School to reapply for their jobs, although state education officials have publicly questioned if that will be enough to prompt real change.

A more comprehensive picture emerged in November, when de Blasio unveiled a $150 million plan to convert 94 struggling schools into community hubs and hold them accountable for improving over the next three years. “We will move heaven and earth to help them succeed,” de Blasio said, “but we will not wait forever.” The announcement won praise, but it also worried some supporters of the plan looking for more information about how the schools would get help improving their academics.

5. The UFT is back in the city’s good graces.

After years of fighting with the mayor, the teachers union has forged a tight partnership with the city. In April, Mulgrew called the mayor “the right man at the right time with the right idea,” and the praise continued from there. Coffee dates with the mayor? Mulgrew said he doesn’t need them — they just pick up the phone and talk.

De Blasio, Fariña, and Mulgrew have spoken as one on issues such as teacher retention, which all have named a top priority, and de Blasio defended Mulgrew when he got into hot water over his private remarks about teacher evaluations. The city and the union have also acted as close partners as city officials roll out plans for community schools, which the union has championed for years. (The union made plans for a few more of their own in June.) And the union has returned the favor by staying quiet when it previously would have raised hell over ongoing frustrations like class sizes.

But the year’s biggest news was a new contract, which included raises, back pay, and changes to teacher evaluation requirements.

Together, city and union officials talked the contract deal up as “transformative,” citing a number of programs that Fariña and UFT chief Michael Mulgrew said would prove that education reform could be done by educators. Digging into the details, we noted that teachers in the ATR pool would have stronger protections than originally noted by officials; found schools doing a variety of things with their newly mandated professional development time; and revealed that schools in the much-touted PROSE experimentation program were limited in what changes to the contract they were able to make, at least in the program’s first round.

6. Candor can backfire.

In her first speech to Department of Education employees, Fariña made it clear she’s not a fan of scripts. “I don’t write my speeches,” she said, holding up a Post-It note she brought with her to the podium. “The first time they gave me a three-page speech I ripped it up.”

But Fariña touched off her first media firestorm with a few casually spoken words — “It’s absolutely a beautiful day out there” — on a day that was in fact quite snowy and when the city’s decision to keep schools open had frustrated many parents. Fariña was noticeably more scripted in her subsequent public appearances, though she eventually adopted “beautiful day” as a sort of personal catchphrase, disarming parent audiences at town hall events by cracking jokes about the weather.

She managed to largely avoid the tabloid covers from then on, though she sparked another critical news cycle more recently by implying that some of the city’s charter schools pushed students out before the state tests.

UFT President Michael Mulgrew got into his own hot water when he was recorded telling members about trying to “gum up the works” of the teacher evaluation system he had negotiated with Mayor Bloomberg. And some sharp 2013 campaign-trail remarks from de Blasio about the city’s most prominent charter-school chief (“There is no way in hell that Eva Moskowitz should get free rent, OK?”) followed him into office and helped spark a bruising fight that made its way to Albany this spring.

7. Some big indicators of educational success are going up, but things are still grim by other metrics.

It was a year of gains. Proficiency scores by elementary and middle school students on state math and English tests ticked up in the second year of Common Core-aligned state tests after tanking in 2013. The share of students graduating high school on time grew by nearly three points last year, while new research showed that low-income students especially thrived at small high schools. Additionally, more city students are taking and passing AP and SAT exams, outpacing growth rates elsewhere in the country.

But the good news came with stark reminders of the challenges that some students continue to face. English language learners were a glaring exception to the higher graduation rates trend. And while city students in all racial and ethnic groups did better on this year’s tests than last year, white and Asian students improved faster than their black and Hispanic peers, meaning that the achievement gap actually widened.

The preferred metrics for academic success shifted further toward “college and career readiness,” where the arrow also pointed up this year. But the percentage of students who left high school with Regents scores high enough to avoid remedial classes increased only from 31 to 32 percent.

8. The meaning of ‘mayoral control’ is changing.

Gov. Andrew Cuomo took a bite out of mayoral control of the city’s school system in April by pushing legislation that required the city to either find space for new or expanding charter schools or cover their rent in private space. The guarantee of taxpayer-funded facilities was a major win for the city’s charter school movement but much less of one for the Department of Education, which previously had wide latitude in choosing which charter schools had access to city-owned buildings.

It was a particular setback for de Blasio, who had said he wanted to charge rent to charter schools operating in public-school buildings, and an example of how the mayor has been forced to share the stage as he laid out a vision for public education in New York City.

While de Blasio has pushed pre-K and community schools, Gov. Andrew Cuomo and Success Academy CEO Moskowitz, who contributed generously to the governor’s re-election campaign, worked together to dilute the mayor’s message with a political and public relations leading up to passage of the charter school legislation. The clearest example of that dynamic was a cold March morning in Albany, when Moskowitz and Cuomo hosted a large parent rally just as de Blasio’s allies were hosting their own event to drum up support for pre-K funding.

Next year could see a further weakening of mayoral control. The state legislation that puts the mayor in charge of city schools is expiring in June, and can’t be renewed without support from Cuomo and Republicans who control the State Senate.

9. The battles over who controls education in Albany are about to grow even more heated.

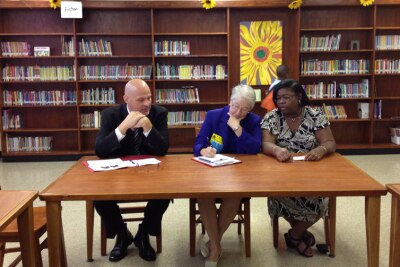

The year is ending with officials at the State Education Department and on the Board of Regents, who control school policy at the state level, in a vulnerable position.

After three years as State Education Commissioner, John King will leave at the end of the month for a top job at the U.S. Department of Education. Though Board of Regents Chancellor Merryl Tisch has promised a quick search for King’s replacement, his absence creates a power vacuum just as Gov. Andrew Cuomo, whose power over education is limited by state law, has expressed disdain for the current governance structure.

Cuomo recently sent aggressive signals that he wants to examine that structure in 2015, along with a host of other education issues, from teacher evaluations and the state’s charter-school cap to teacher tenure policy. Meanwhile, the Regents are facing their own leadership gaps: They need to fill two vacancies and another five members must go through the appointment process, which culminates in a vote by the legislature.

10. The teacher-quality debates have a new battleground.

There is a new frontier in the battles over teacher quality: the courtroom.

Inspired by a preliminary ruling against teacher tenure in a Los Angeles lawsuit in June, parents, lawyers and activists brought a similar case in New York that argues students’ constitutional rights are violated by state laws that protect the jobs of weak teachers.

That began to shift the debate from the singular focus on teacher evaluations of the last few years. Meanwhile, the push for more stringent evaluations lost some political steam in 2014, the first year New York City teachers earned a rating under the new system. Teachers and principals took issue with the complexity of the new observation process, and support for using state tests in evaluations during the transition to Common Core waned. Still, more than 90 percent of city teachers were rated effective or highly effective, a figure that Gov. Andrew Cuomo insisted “doesn’t reflect reality.” Now, he and King say the evaluations need another round of changes, setting up a fresh legislative battle.

Despite some infighting between the groups who are hoping to change teacher protection laws, the lawsuit they’ve filed is winding its way through New York State Supreme Court. Teachers unions have joined the fight and filed motions to dismiss the case, and the plaintiffs responded in December. If a judge rules that the case can move forward, its proceedings will become a major story in 2015.

11. School segregation was the sleeper issue of the year.

De Blasio came into office pledging to address the “tale of two cities,” though many indicators of diversity trended further down this year. In March, UCLA researchers called New York’s schools the most segregated in the country, a distinction earned largely because only a quarter of black and Latino students in New York City attend schools diverse enough to be considered multiracial. (That report also enraged some charter-school advocates for calling many of the city’s charter schools “apartheid” schools.)

“If you don’t have an intention to create diverse schools, they rarely happen,” researcher Gary Orfield said.

The city’s response to those numbers (which themselves weren’t revelatory) was unspecific, as a few of Chancellor Fariña’s other comments on issues of admissions and diversity have been. That has disappointed some advocates who hoped that Fariña would take a more aggressive look at the notoriously difficult-to-solve issue.

The one fight de Blasio has been eager to pick has been over admissions policies for the city’s specialized high schools, which the mayor has said should be changed from a single-test method to one that assesses multiple measures to increase diversity — a position that has divided alumni groups, City Council members, and the public. Just 11 percent of offers to eight of those schools went to black and Hispanic students this year, though they make up 70 percent of the city’s eighth graders. Meanwhile, gifted and talented programs are still attracting a disproportionate share of affluent students, and some schools and community school districts continued to take up the fight for more diverse schools themselves.

12. As interesting as policy debates can be, being on the ground is often more compelling.

Chancellor Carmen Fariña said in August that school visits are “the only way you get the information that you need in order to do your job.” That’s the same attitude that we have at Chalkbeat, and our time spent visiting classrooms produced some of our favorite stories of 2014.

We learned how reading music helped boost language acquisition for English language learners at Voice Charter School in Queens and accompanied Deputy Chancellor Phil Weinberg on a nostalgia-filled trip to his former school. We narrated the fast pace of an award-winning teacher’s science class and a Bronx middle school teacher’s Common Core-aligned lesson on a centuries-old poem.

Some visits, like one to a high-performing Success Academy elementary school and another in which we tagged along with Queen Letizia of Spain, received more attention than others. The mayor’s inaugural first-day-of-school tour served as a pre-K victory lap and as a glimpse at what schools most interested Fariña and de Blasio. Other visits focused on quieter work, like one to John F. Kennedy campus in Marble Hill where the schools were sharing lessons through Fariña’s new Learning Partners Program.

Not all of our on-the-ground stories were as sunny. We also documented a charter school board’s tepid response to revelations about a principal’s dishonesty about his credentials; followed students and staff on graduation day at Christopher Columbus High School before the school was permanently shuttered; and met a Boys and Girls High School student who said he was pressured to leave amid the school’s turnaround efforts.

The end of 2014 also marks our first year as Chalkbeat New York, though one of our New Year’s resolutions remains the same as always: to visit more schools and meet more of our readers. Where should we start?