Christine Rowland is a teacher and professional developer at the UFT Teacher Center at Christopher Columbus High School. She has been at Columbus since 2002.

On Monday, a team from the Department of Education walked into Christopher Columbus High School to announce that it would be closed. It was a profoundly upsetting day for our entire community (on Pearl Harbor Day, as Columbus’s UFT chapter leader Donald March pointed out). I would like to take this opportunity to address the issues surrounding this decision and to appeal for a reversal.

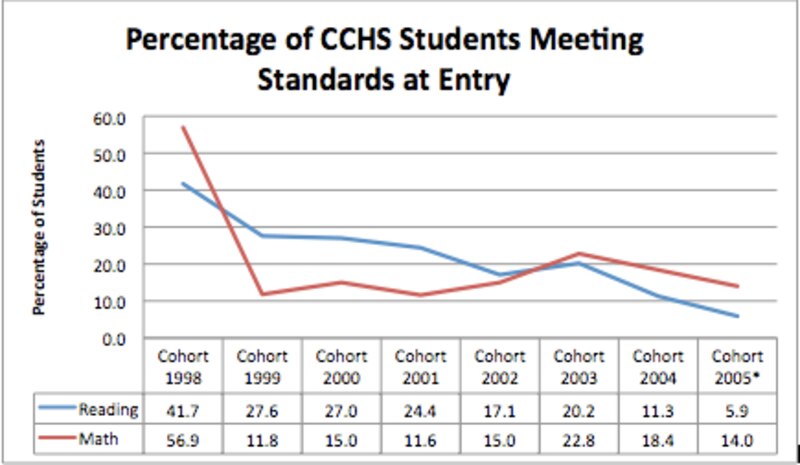

Until several years ago, Columbus was a school that contained a diverse student body not only in terms of races, nationalities and language backgrounds, but also abilities. In 1998, 41-56% of the entering freshmen and sophomores were on grade level in reading and math at entry. By 2005, this number dropped to 5.9% of entering freshmen in reading and 14% in math.

In concert with this drop in the skill level of entering freshmen, there was a steep rise in the percentage of special education freshmen from 6.8% to 23.6% of our graduation cohorts:

Did the school accept students with very high needs previously? Absolutely. But this was not the sole mission of the school. Several years ago the Bronx High Schools Superintendent’s Office broke off our prestige programs designed to meet the needs of our most able students into separate schools: Collegiate Institute for Math and Science, Pelham Preparatory Academy and Astor Academy. High-performing students who had once come to Columbus instead went to these schools, as did many experienced and skilled educators. In addition, New World Academy opened nearby with Columbus educators as an ELL-only school. These schools see students who are far lower in need.

Columbus’s great good fortune was that, as the changes took place, Lisa Fuentes, a seasoned special educator, was made principal. She has worked tirelessly, extremely long hours and frequently seven days a week to help our students become successful.

Columbus initially reeled under the changes as classes became more challenging both academically and behaviorally. The school was initially badly overcrowded at 180% of capacity and on an end-to-end schedule (juniors and seniors 7 a.m.-12:30 p.m. and freshmen and sophomores 12:30-6 p.m.), and the school went on the dreaded Impact list of schools suffering from high levels of violence. As a community we fought for equity and worked hard to reorganize ourselves into smaller learning communities. The efforts paid off as our environment improved physically, culturally, and in terms of safety.

We also learned that the same old practices were not sufficient to meet the needs of our most vulnerable students. In response, we changed the way the school was structured so that we could offer stronger instruction that is tailored to each student’s needs. We launched new programs in each of the last three years designed to meet the special needs of our most vulnerable students, including those under pressure to work, those who are pregnant or parenting, and those returning to school after being in jail. In addition, we launched separate advisory programs for male and female students.

The DOE gave four reasons for phasing out Columbus.

First, the department stated that our graduation rate was 36.9% in 2007-8. This is not accurate. This was the four-year graduation rate after the DOE had placed 26 formerly ungraded special education students back into the cohort after the end of the school year as a result of changes in federal regulations regarding the consideration of special needs students. The DOE, recognizing the unfairness of the situation, in a July 2008 memo agreed not to penalize schools because of these students. After adjustments were made the 4-year graduation rate was 40.1%, and our weighted 4-year graduation rate (a progress report measure that takes into account how challenging the student population is) became 68.8%. But the issue is deeper for us because many of our students take five, six, or even seven years to graduate. Columbus’s most recent 7-year graduation rate (published under longitudinal reports on the DOE Web site) was 81.5%, compared to a city average of 72.2%.

Second, the DOE charges that first-year credit accumulation is low, with only 49.4% of first-year students accumulating 10+ credits in their first year. Removing first-year students who were sent to Columbus throughout the year improves this number to 54.1%. These students are frequently enrolled only for a brief period and are going through additional challenges in their lives that make high credit accumulation particularly challenging. The figure for our non-special education students with 10+ credits was actually 60.2%.

Third, the DOE asserts that demand for the school is low. This year 292 students elected to come to Columbus through the high school application process. We have accepted another 182 “over the counter” so far this year. Considering that fact that our overall enrollment is only 1,400 this would seem to indicate that there is plenty of demand for the school. We believe that we have an extensive array of offerings in the fine arts, music, culinary arts, and technology that, along with a wide range of extra-curricular opportunities, make Columbus attractive to students who are looking for more than reading, writing and arithmetic.

Fourth, and finally, we received a D on our 2008-2009 Progress Report, down from a C in 2006-7 and 2007-8. Last year we received 100% of our performance bonus for an improvement that amounted to approximately 17% after adjustments were made for changes in the metrics. This year we made a 13.8% gain in total over last year — improving again. The reason the grade went down was because the DOE changed the targets. Had we received exactly the same score as last year we could have received an F. Our Environment category actually showed a 31% gain — up in every single category and we STILL went down from a B to a C in that area. The reality is that there are many flaws with the progress reports (some of them have been outlined here and here). While we have the second lowest peer index (population challenge level) of any of the 372 high schools receiving a progress report, the peer index does not reflect the proportion of students with special needs who have been identified as requiring the most restrictive environment. A simple comparison of A and D schools on the progress reports show that D schools have four times the most restrictive environment students as A schools.

So how does all of this affect our current student body? Many of our students were deeply upset over the announcement. There was shock and pain, tears, hugs and anger. They will fight nobly, I’m sure, to try to keep their beloved school (see the SAVE COLUMBUS Facebook group with more than 900 members as of writing) for as long as there is hope. We will try hard to keep up their spirits and to help them try to refocus on achieving academic success, but Columbus is much more than a school to so many of them (please see our video on YouTube for an illustration). Teachers will see that they stand to be made ATRs and will make the gut wrenching choice to either stay and support the students they care for so deeply, putting their own future at risk, or will polish their resumes and try to find a small school placement as rapidly as possible. In this environment students will lose many of the teachers they love and trust and the environment will deteriorate. This will impact all schools in the building. We know that under such circumstances their opportunities will also suffer.

I’m also concerned about what will happen to the students who would otherwise attend Columbus. Small schools cannot accommodate many students with significant needs. These students are likely to wind up at other large schools in the area, such as Truman and Lehman, which will receive a massive influx of extremely needy students including late-entry immigrants with little or no English, and the most needy special education students. A report that came out last summer proved what is obvious: Other big schools suffer when a large school gets closed. It will take time for the new receiving schools to adjust their instructional practices and programs to meet the needs of the changing population. These schools will be the next targets for closure just the way we have taken those who would at one time have been placed in Evander or Stevenson.

It seems there is a political agenda driving where students are placed. OSEPO (Office of Strategic Enrollment, Planning and Operations) would, I’m sure, claim that they place students in the schools that can best meet individual student needs, but as long as the Office of Accountability engages in evaluative practices that effectively punish such schools, the fatal combination of the actions of the two offices of the Department of Education would seem to be showing a disregard for the well-being of children.

Right now our longer term outcomes are relatively good for our students, helping them along the path to graduation even when they take more than four years. Those students with severe special needs are helped as frequently as possible with work study programs that provide them with job skills, and frequently job placements on leaving the school. We ask that the DOE reconsider their decision and give the Christopher Columbus community the reprieve it deserves. Outcomes can be improved by creating a more equitable situation around school enrollment. We all need a holiday miracle.

About our First Person series:

First Person is where Chalkbeat features personal essays by educators, students, parents, and others trying to improve public education. Read our submission guidelines here.